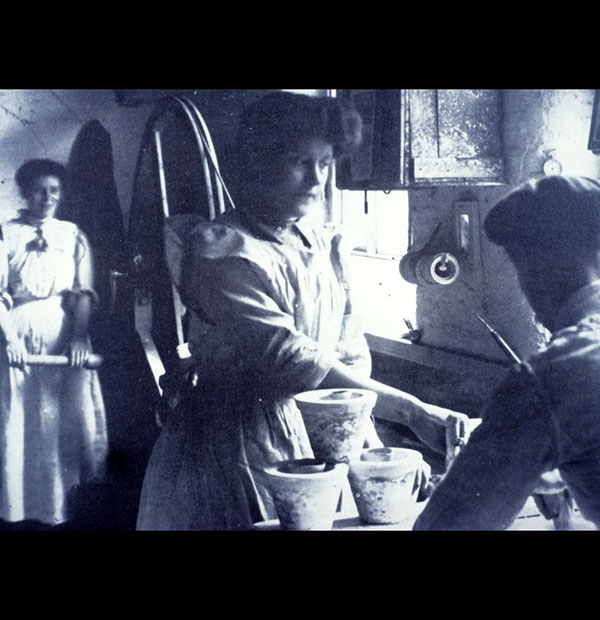

March 8th is International Women’s Day and at WMODA we are looking at the important role played by women in the British ceramic industry during the 19th century. In the Staffordshire Potteries women worked as assistants to their menfolk and were a hidden workforce. They were often involved in strenuous labor, such as wedging the clay, turning the potter’s wheel and running to the drying room with the finished pots.

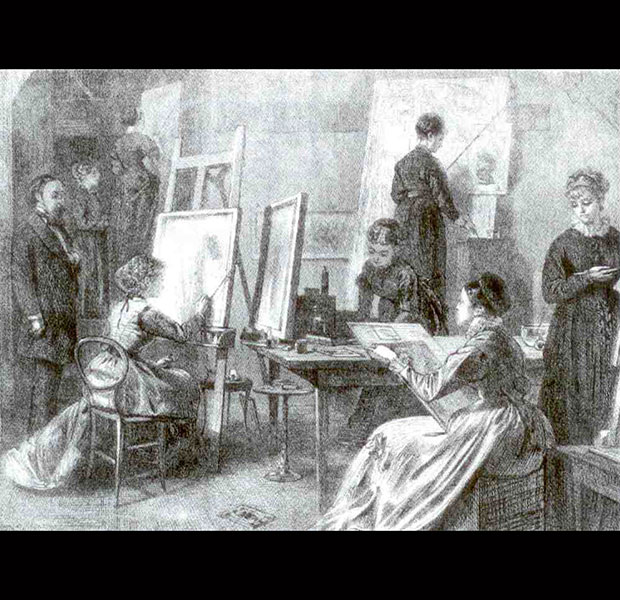

Some of the luckier girls worked as decorators, transferring engraved prints to the pottery. The most privileged position in the Potteries was painting but initially men dominated the art studio and restricted women’s access to armrests and gold so that they could not do the finest, highest paid work as china painters and gilders. The situation was very different in London where pioneering studios run by Minton and Doulton began to employ young women from 1870 onwards.

In the mid-19th century, the number of genteel young women obliged to seek employment became a pressing social problem. Many would not be able to fulfill their natural destiny and marry Mr. Right as there were a million extra women of marriageable age in England. In Victorian times, a woman’s place was in the home as the “angel of the household” and marriage was her sole sanctified vocation – her only means to social recognition, status, and security. Formal education for women was not customary and ladies avoided contamination from the sordid male commercial world at all costs.

In 1835, a Select Committee was set up to inquire into Art education in England. A National School of Design was established in London for men in 1837 and for women in 1842. Government support was withdrawn for the Female School of Design in 1859 but it carried on independently. The school catered for needy gentlewomen 13-30 and discouraged women who were seeking training principally for an accomplishment. Places were given to those who demonstrated a need to work. One of the more preposterous suggestions to deter those who left artistic careers to marry was that only ugly women be admitted to art schools! By the 1850s, art schools for men and women were being established in many parts of Britain and eventually there was one for each of the six Potteries towns in Staffordshire.

There were very few occupations deemed suitable for genteel women in the early Victorian period beyond being a governess. In search of suitable occupations, art rapidly came to be recognized as one of the few areas in which women’s participation could safely be encouraged as an extension of their traditional accomplishments. Decorating art pottery, in particular, became a dignified means to lady-like independence. China painting classes were held at the government’s South Kensington school and from 1866-70, ladies were employed making ceramic decorations for the refreshment rooms of the Victoria & Albert museum. They were paid 6d an hour for their efforts painting the Seasons and the Months.

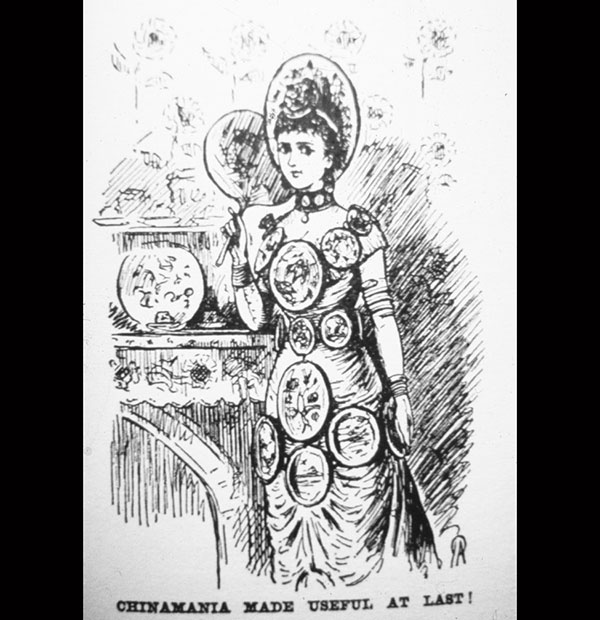

Encouraged by the success of this venture, Colin Minton Campbell set up an art pottery studio next door to the school in 1871 and 20-25 ladies of good social standing were employed to paint on pottery. The Minton studio was well patronized by important customers and royalty but the premises were destroyed by fire in 1875. This new fashion for painting on pottery plaques and tiles inspired other major manufacturers and retailers to look seriously at this form of decoration. In 1876, Howell & James in Regent Street launched their first annual china painting exhibition showing 500 pieces by amateurs and professional artists. By 1881, over 2,000 pieces were being exhibited. Pottery painting classes were also held by a former artist from the Minton studio. The vogue was satirized in contemporary magazines “Chinamania made useful at last.”

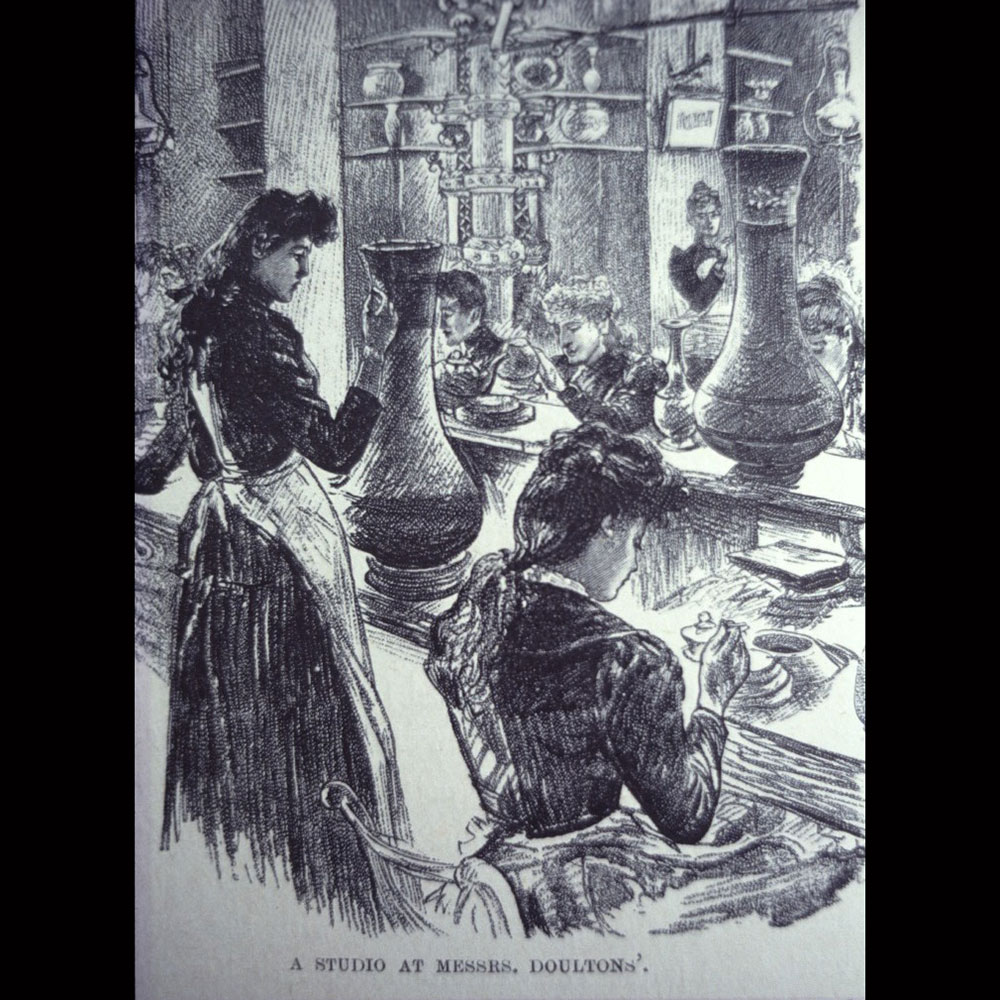

In the late 1860s, the principal of the Lambeth School of Art persuaded Henry Doulton to provide free clay and firing facilities for his students at his Lambeth factory. This co-operation eventually led to the employment of the first resident artists. Hannah Barlow was the first lady in 1871 and she remained until her death in 1913. “Sir Henry was always so encouraging. I could not help but enjoy my work. In all the years I have worked at Lambeth, I never felt that I was working for money. That has been one of the great charms of my work there. Sir Henry’s enthusiastic interest always made me feel raised to do better work.”

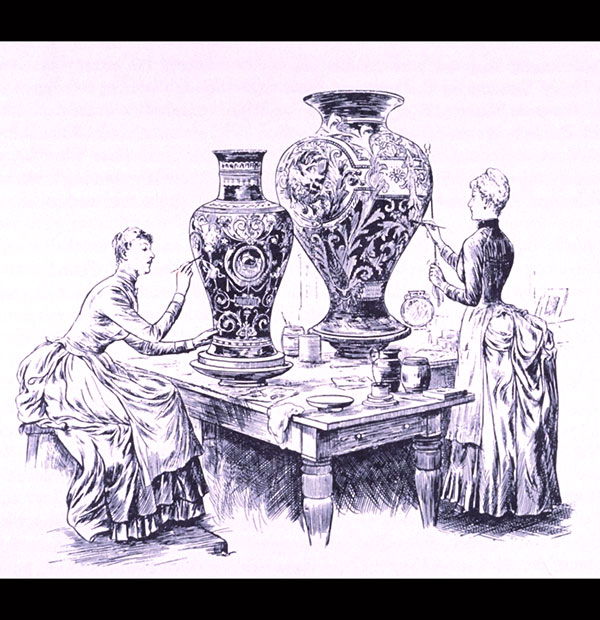

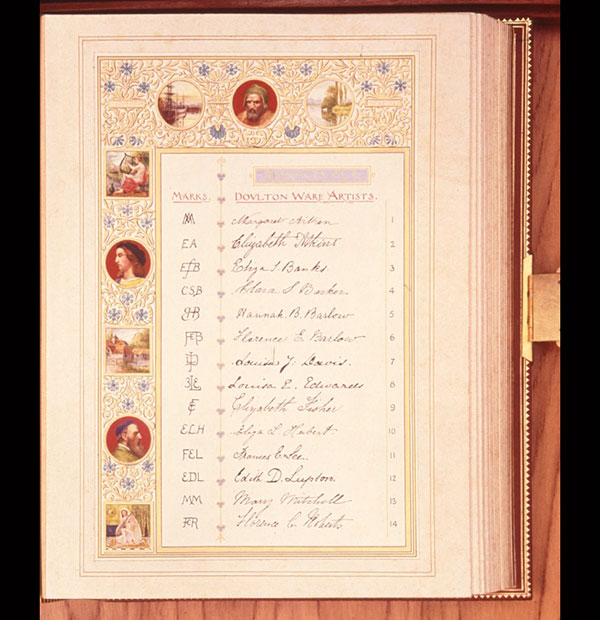

Hannah’s sister Florence joined the studio together with a group of women from the art school and to mark the 10th anniversary of their employment in 1882, 229 lady artists of Lambeth presented Henry Doulton with an illuminated album “to take this opportunity of expressing our obligations to you for the origination of an occupation at once so interesting and elevating to so large a number of our sex.” By the mid-1880s, over 300 women were employed at the Doulton studio decorating stoneware and Faience art pottery and were crucial to establishing his international reputation.

Related Articles:

A Bizarre Affair

Daisy's Dark Side

Girls at work in the Staffordshire Potteries

Slip casting in Staffordshire

Transfer printing useful household wares

Angel of the Household by W. Crane

Punch cartoon showing the limitations of the crinoline

Punch cartoon ridiculing Chinamania pottery painting

Minton Advertisement

Women painting Lambeth Faience at Doulton’s of London

Illustration of Doulton artists from Queen Magazine

Artists at work in Doulton’s Lambeth Studio

Hannah and Florence Barlow working in the Doulton Lambeth Studio

Illuminated book presented to Henry Doulton by female artists