By Louise Irvine

The Humorous and Grotesque Art Exhibition was held in London in 1889 and a photograph from the Doulton archives gives us some insights into quirky Victorian humor. The exhibition featured work by two of the Lambeth studio’s leading sculptors, George Tinworth and Mark V. Marshall, who continue to amuse us today with their whimsical works.

The Humorous and Grotesque Art Exhibition 1889

Marshall’s Beautiful Uglies

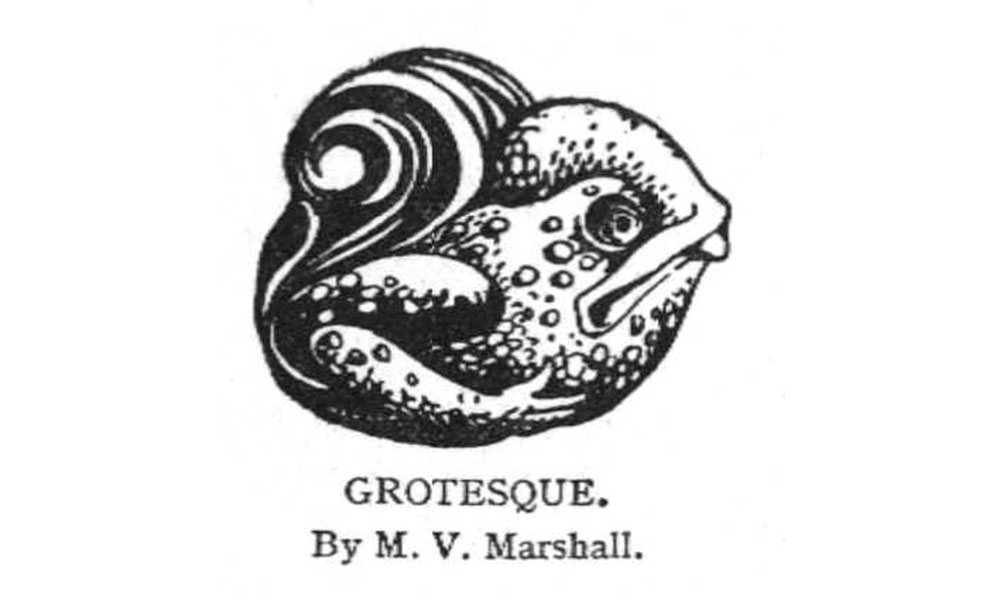

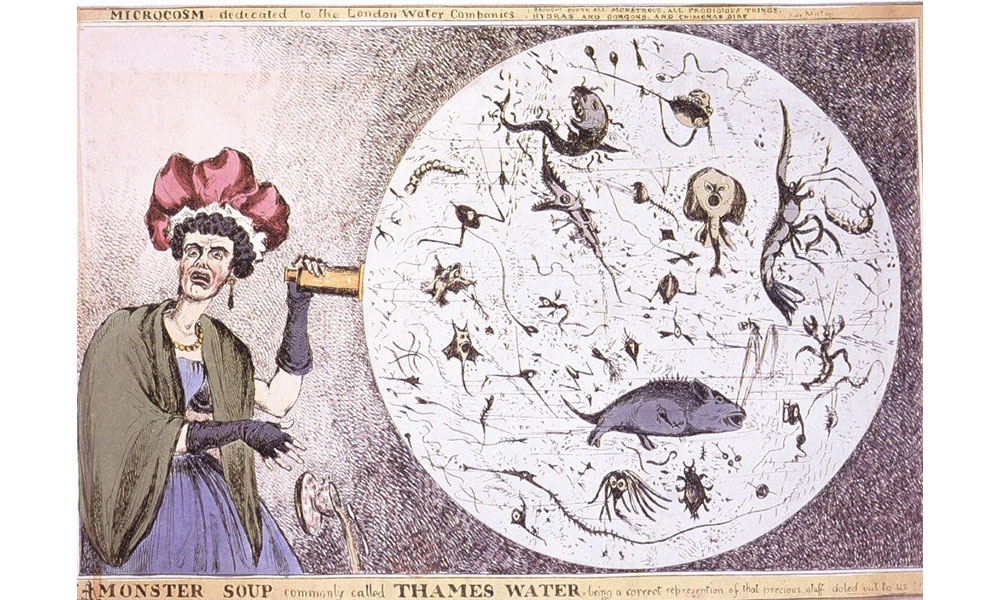

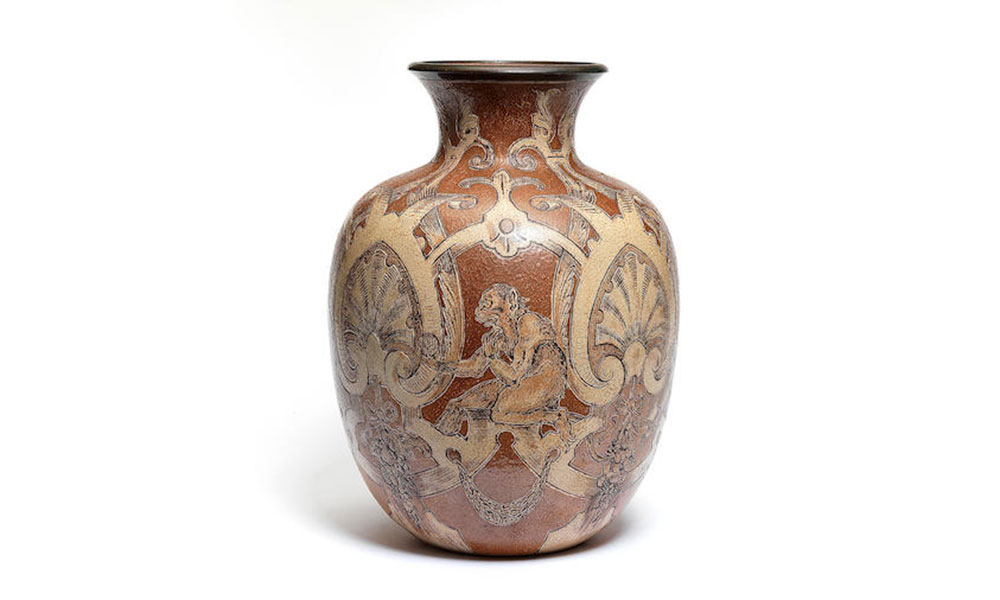

Mark Marshall’s impish sense of humor pervades his work, and he entertained visitors to the Doulton Lambeth studio with his playful wit. Sometimes, he caricatured his fellow artists’ faces on his strange stoneware paperweights, known as his “beautiful uglies,” which he modeled as “easily as a bird sings.” His early work for the eccentric Martin Brothers developed his peculiar vision, particularly of underwater creatures. Perhaps he was familiar with William Heath’s cartoon showing the polluted water from the Thames River through a microscope. Monster Soup revealed all types of “hydras, gorgons and dire chimeras,” which influenced Marshall’s monstrous stoneware fish. His googly-eyed pufferfish was obviously popular and is found with varied expressions.

Doulton Paperweight by M.V. Marshall

Beautiful Ugly by M.V. Marshall

Beautiful Ugly by M.V. Marshall

Mark V. Marshall

Doulton Waning of the Honeymoon by M.V. Marshall

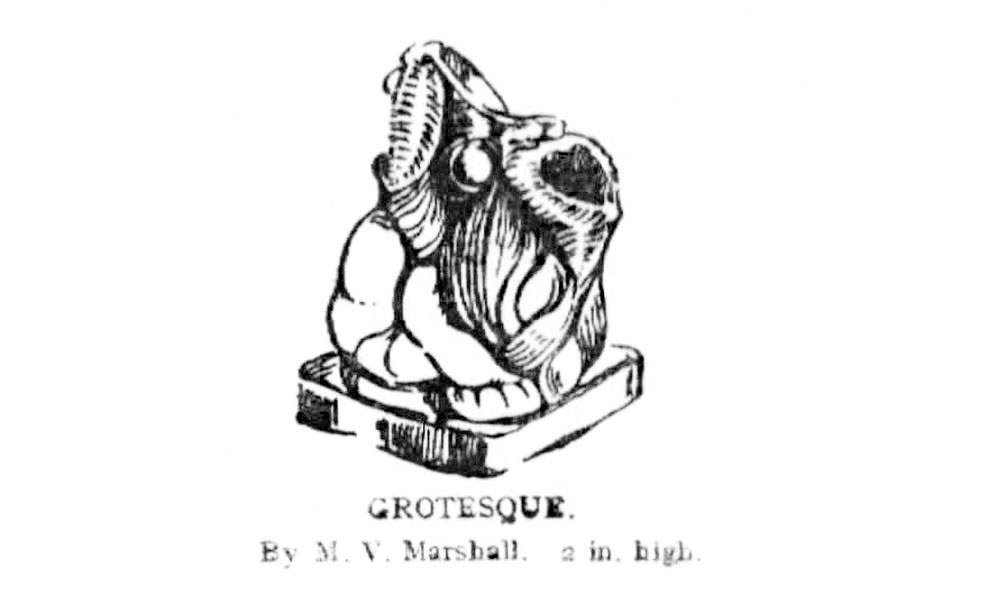

Hedgehog and Rabbit Victorian Style

Humorous & Grotesque Art Exhibition

Marshall’s interpretation of the Waning of the Honeymoon in 1880 was the first Doulton subject to feature clothed animals acting as humans. The jaded rabbit couple represents the Victorian fascination for the relationship between man and animals, prompted by Charles Darwin’s Origin of the Species, which expounded our descent from apes. Cartoonists responded in the popular press with illustrations of all sorts of animals endowed with human characteristics. One of Mark Marshall’s oil lamps depicts some very strange ape-like figures, a fascination he shared with the Martin Brothers.

Doulton Puffer Blow Fish by M.V. Marshall

Doulton Puffer Blow Fish by M.V. Marshall

Martin Brothers Sea Life

Monster Soup Thames Water by W. Heath

Puffer Blow Fish

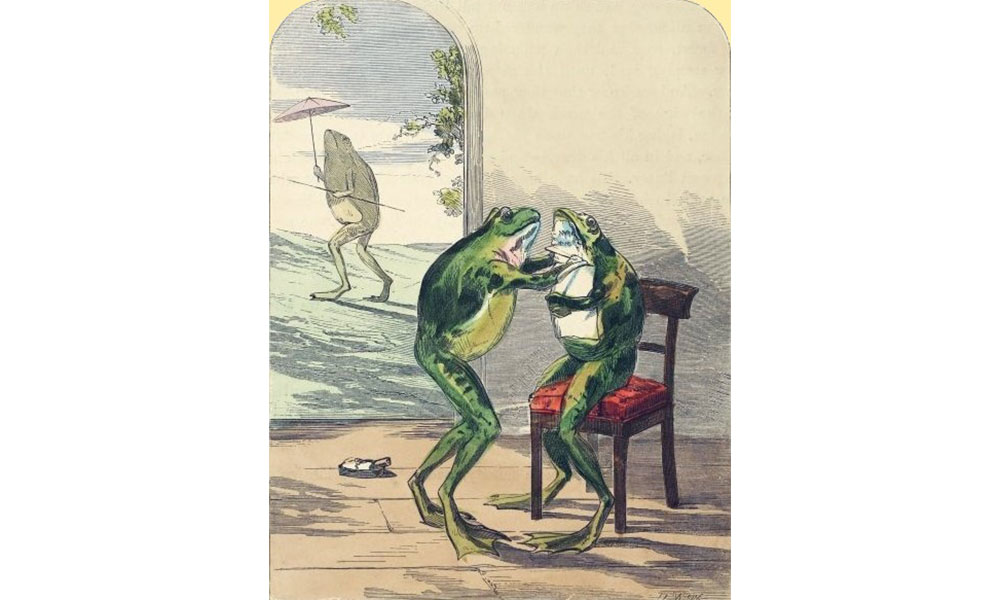

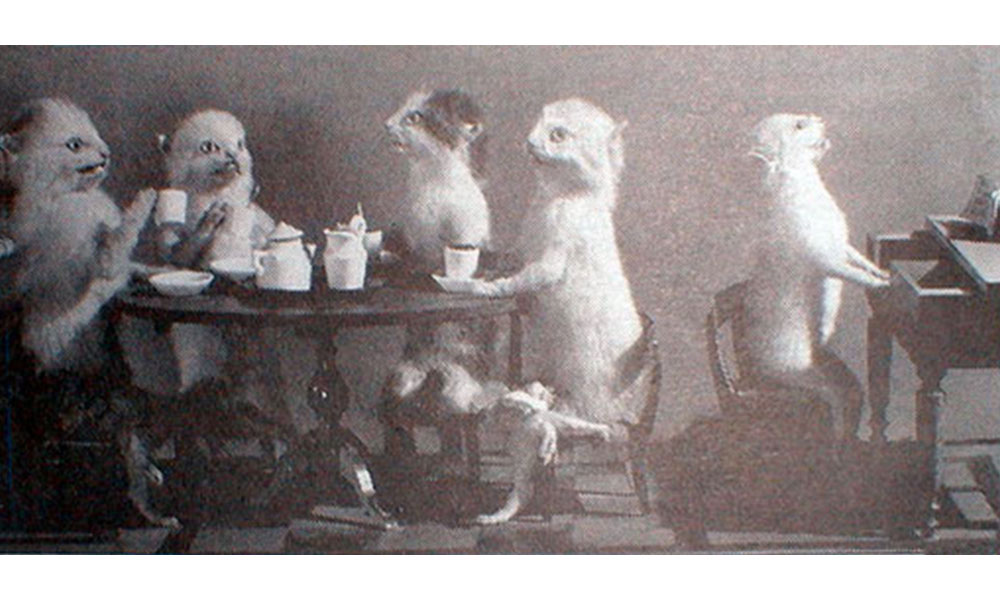

Taxidermists also contributed to this anthropomorphic trend. Hermann Ploucquet’s allegorical dioramas of kittens taking tea and frogs going a-wooing delighted Queen Victoria at the Great Exhibition in 1851. In her diary, she described the whimsical scenes as “really marvelous.” Engravings of the tableaux were published the following year in a popular coffee table book The Comical Creatures from Wurtemberg. These comic creations later inspired amateur taxidermist Walter Potter to create his own Museum of Curiosities in Sussex, featuring rabbits at school and kittens at a wedding.

Frogs A Wooing Engraving of Ploucquet's Taxidermy

Kittens at Tea Engraving of Ploucquet's Taxidermy

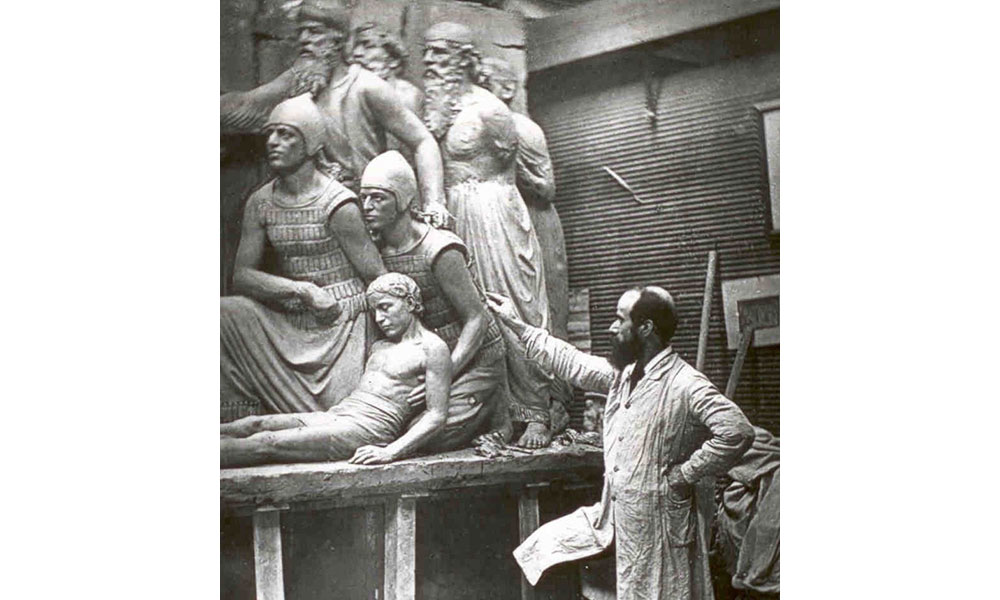

Kittens Taking Tea by H. Ploucquet

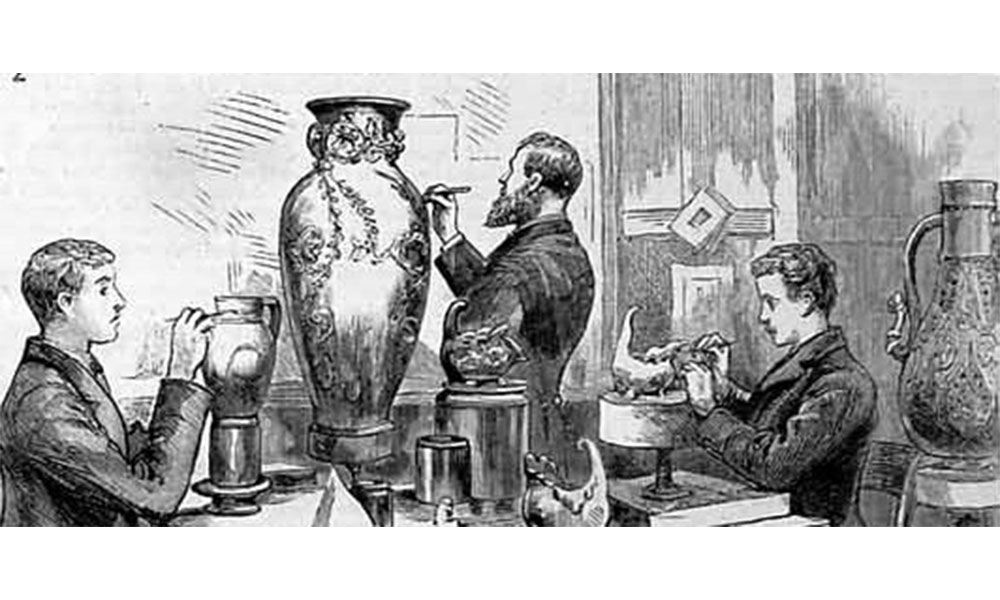

Writers, notably Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll, invented some fantastic creatures in their books, which also fueled Mark Marshall’s fertile imagination. He was often inspired by the weird and wonderful creatures from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and Through the Looking Glass, which were among the most popular books of his time. His bizarre stoneware Rath vessel, depicting a boar-like creature sprouting foliage, can be seen in the archive photo at the top of this page. It must have been a popular piece as his assistants can be seen decorating them in an 1886 issue of The Graphic magazine.

Martin Brothers Apes Vase

Martin Brothers Vase Detail

Doulton Oil Lamp by M.V. Marshall

Doulton Rath by M.V. Marshall

Doulton Rath by M.V. Marshall

Raths, Borogrove & Toves by J. Tenniel

Mark Marshall and Assistants Graphic Magazine 1886

Tinworth’s Humoresques

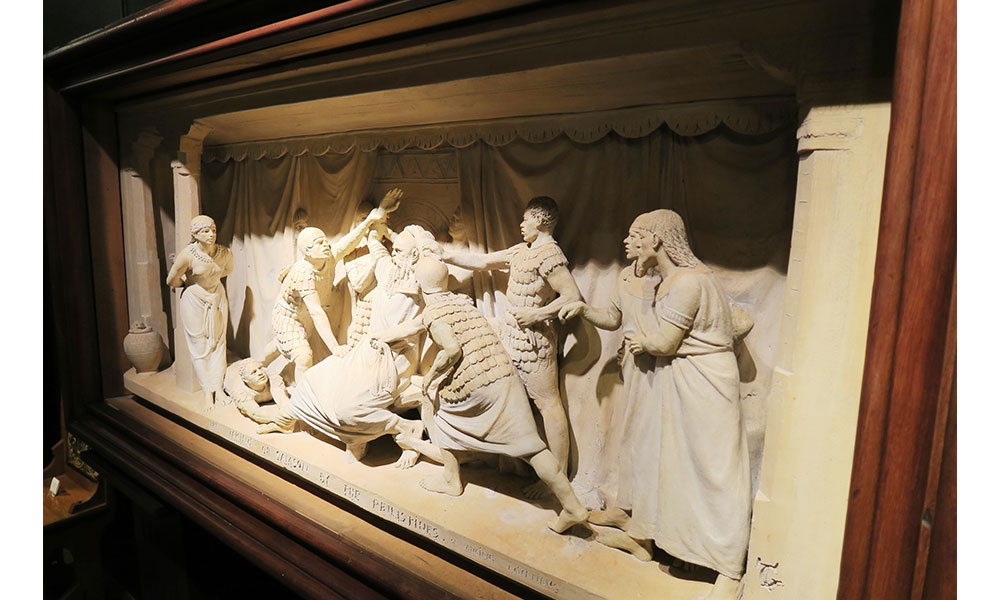

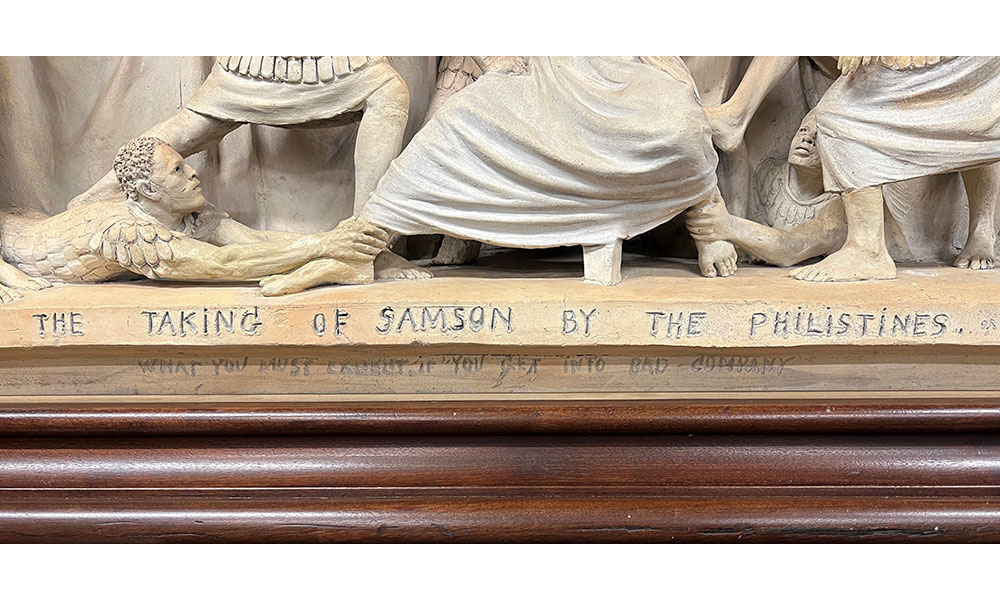

George Tinworth was renowned for his devout religious work, but his mischievous sense of humor sometimes creeps into his “Sermons in Terracotta.” In his sculpture of the Taking of Samson by the Philistines, a laughing monkey pops out of a Doulton jar behind Delilah. Close inspection of the panel also reveals a scrawled subtext “What you must expect if you get into bad company.”

Doulton The Taking of Samson by G. Tinworth

Taking of Samson Subtext

Laughing Monkey Detail

George Tinworth

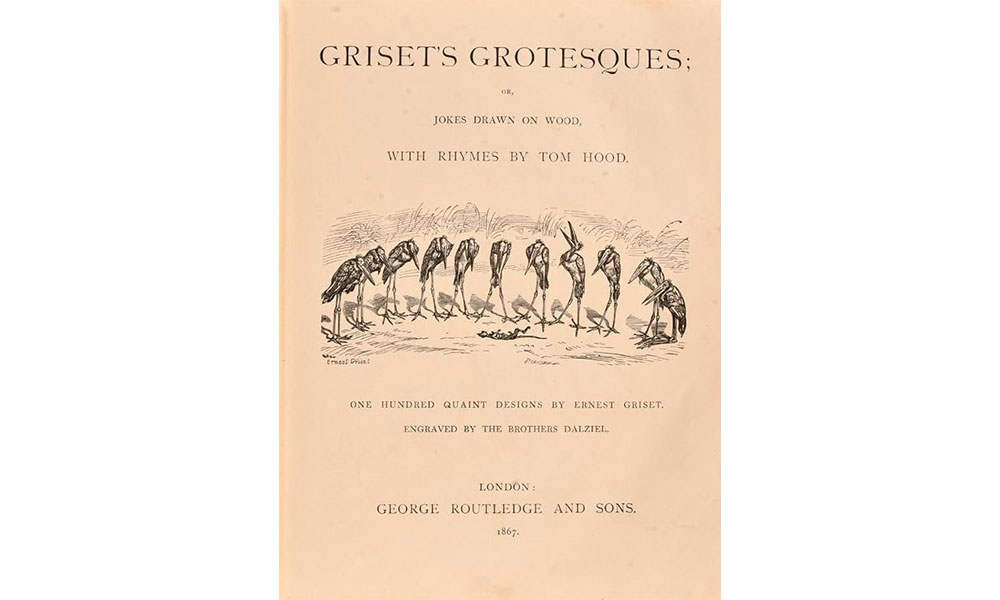

Griset's Grotesques

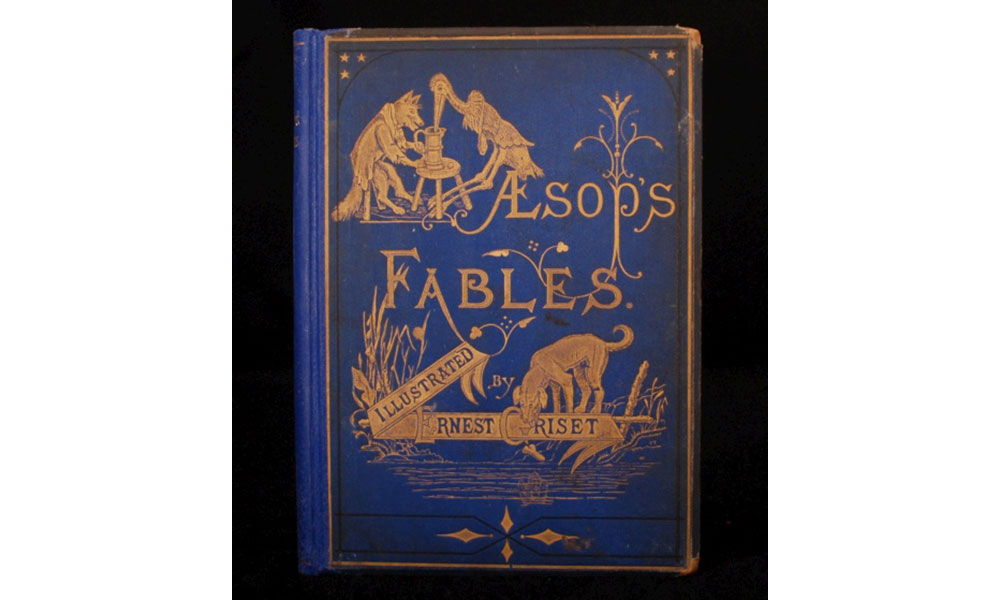

Aesops Fables Ernest Griset

Apart from the Bible, George Tinworth’s favorite book was Aesop’s Fables in which animals act and converse as if they were human to exemplify a moral tale. Ernest Griset, the Victorian illustrator, visualized the ancient Greek fables in 1869 and was highly regarded for his ability to invest animals with human attributes. Griset’s illustrated fables were very popular with Victorians, and their droll illustrations were familiar to Tinworth. One of Tinworth’s strangest models at WMODA features the fable of a lady frog puffing herself up to be as big as an ox. The moral of the tale is to aim high but not attempt the impossible.

Doulton Frog Canoist by G. Tinworth

Doulton Combat by G. Tinworth

Doulton Cricketer by G. Tinworth

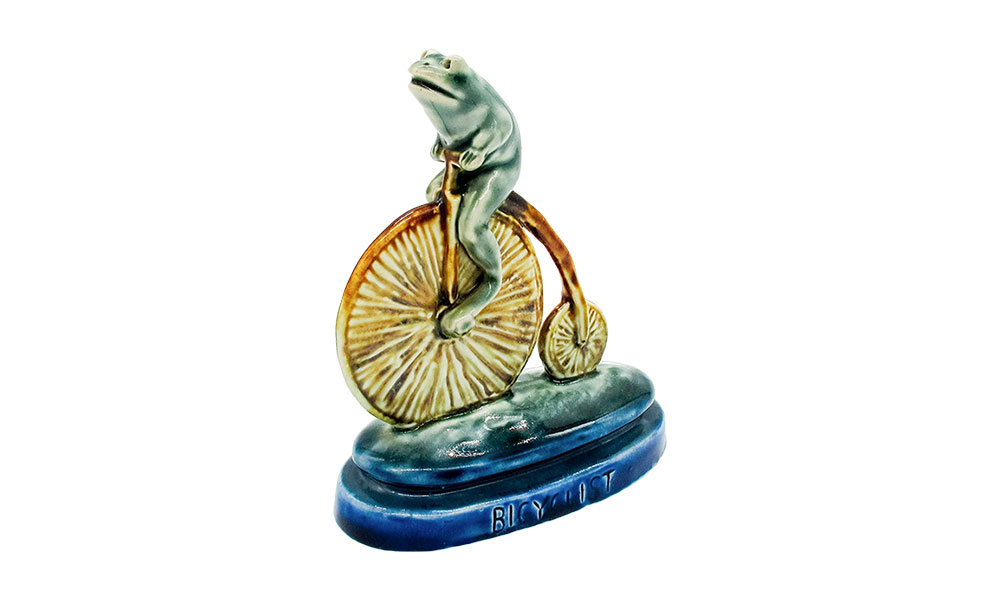

Doulton Frog on Penny Farthing by G. Tinworth

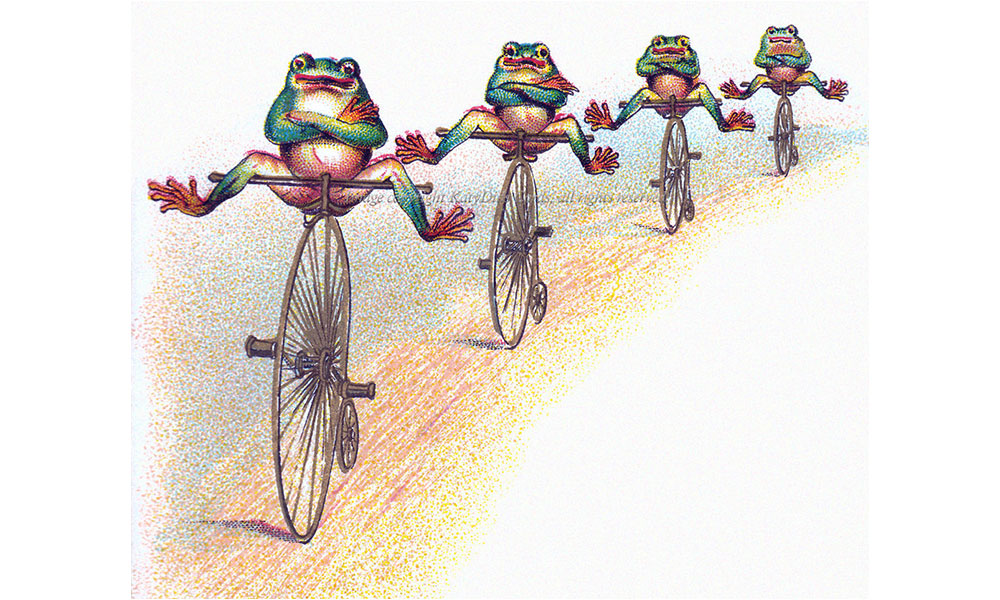

Cycling Frogs Christmas Card

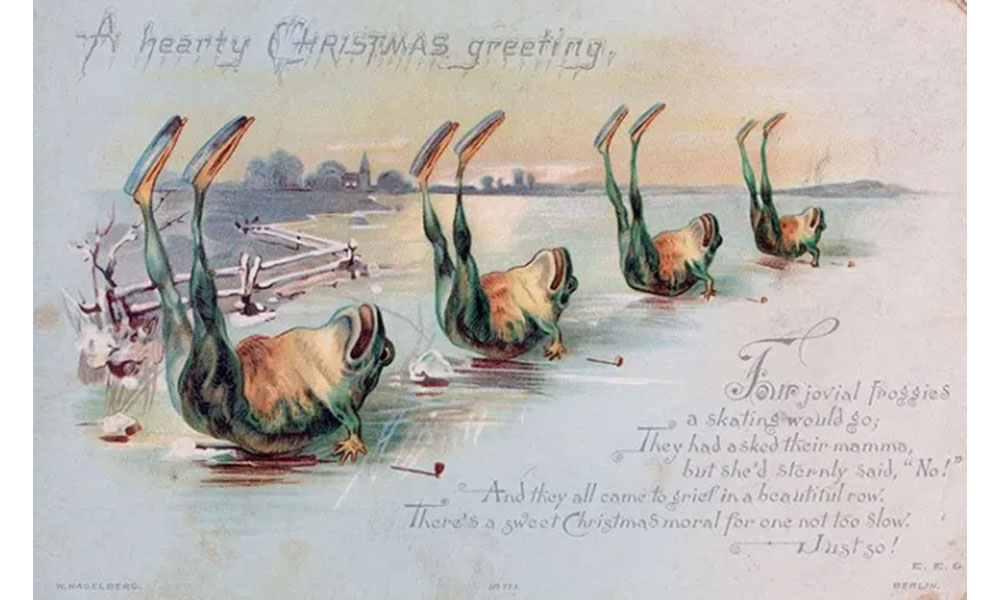

Skating Frogs Christmas Card

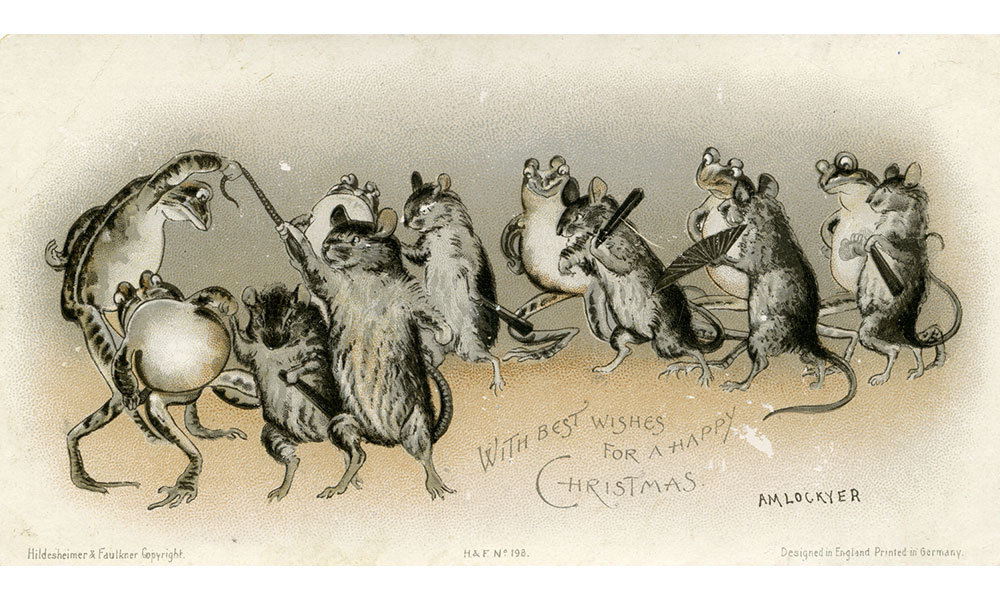

Hildesheimer & Faulkner Frogs and Mice Christmas Card A. M. Lockyer

Battle of Frogs and Mice by T. S. Kittelsen

Frogs were surprisingly popular on Victorian Christmas cards, which depict them singing, skating, and even riding penny farthing cycles. It is hard for us today to associate the spirit of the festive season with such bizarre images but Victorians obviously appreciated the funny side of anthropomorphic frogs. Many enjoyed the Batrachomyomachia, the Battle of the Frogs and Mice, an ancient Greek epic parody of Homer’s Iliad, which underscores the futility of war. It tells the tale of Pufferthroat, the frog king who accidentally lets Crumbsnatcher the mouse drown, causing a retaliatory conflict. Tinworth’s Combat depicts frogs and mice as antagonists although they often play happily together.

Doulton Drink by G. Tinworth

Doulton Cockneys at Brighton by G. Tinworth

Doulton Mouse with a Wheelbarrow by G. Tinworth

Doulton The Potters by G. Tinworth

Doulton The Sculptor by G. Tinworth

Doulton Scandal by G. Tinworth

Doulton Scandal by G. Tinworth

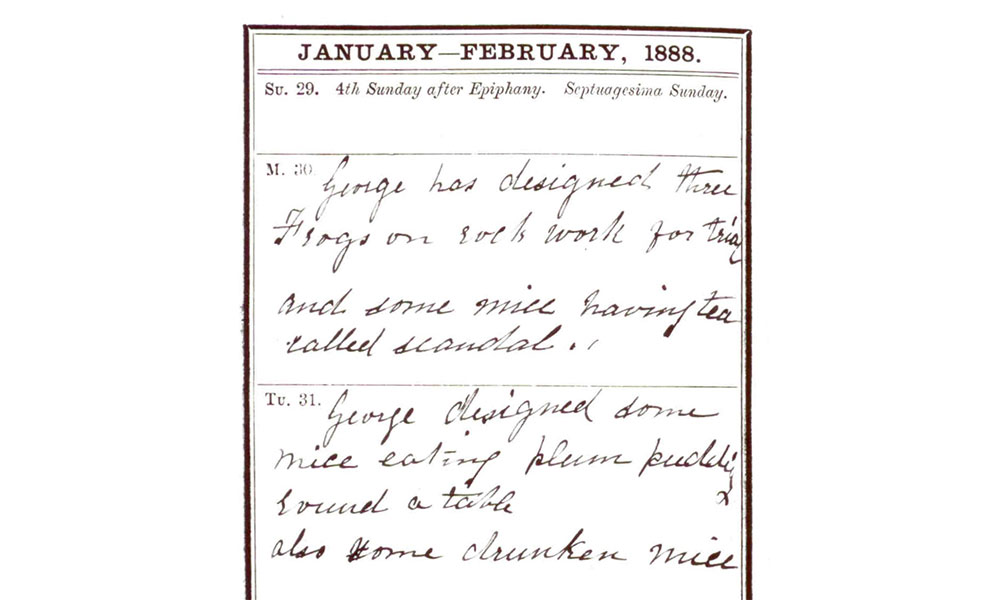

Apparently, George Tinworth’s sculpture studio was invaded by mice who munched their way through his papers and clothes. Rather than trap them, he watched their antics and visualized them in human situations as little salt-glazed stoneware “humoresques” as he called them. They were first portrayed playing musical instruments in 1884 for the Exhibition of Inventions and Music. They proved so successful that he soon envisaged many other amusing activities for his little mice. His wife’s diary from 1888 records him modeling a group of mice at a tea party called Scandal which can be seen in the photograph from the Humorous Exhibition. Teatime Scandal is on display in the Cheers exhibition at WMODA along with a group of drunken mice.

Mrs. Tinworth's Diary

Some of Tinworth’s mice models were exhibited at the Royal Institute in February 1888 during a lecture by Sir Henry Doulton. Mrs. Tinworth recorded how “nice and quaint” they looked on show in the library. Tinworth was asked to model the mice all over again as Sir Henry wanted some for himself and a selection for the showroom as well. He enjoyed displaying them on his dinner table as conversation pieces. We can only imagine the reaction to the drunken mice with one collapsed under the table or the jolly Cockneys boating party with a sea-sick mouse.

Read more about humorous pieces at WMODA

Teatime Scandal | Wiener Museum

Christmas Waits | Wiener Museum