This Doulton clock, teeming with mice enjoying a Menagerie show, is the latest addition to our Carnival & Cabaret exhibit, courtesy of collector Don Kendall. Coincidentally, the last living link to the tradition of traveling menagerie shows died last month in Paris. Rosa Bouglione, the doyenne of the European circus, was 107. She began her career in her family’s Menagerie Van Been as a Loie Fuller style serpentine dancer in a lion’s cage.

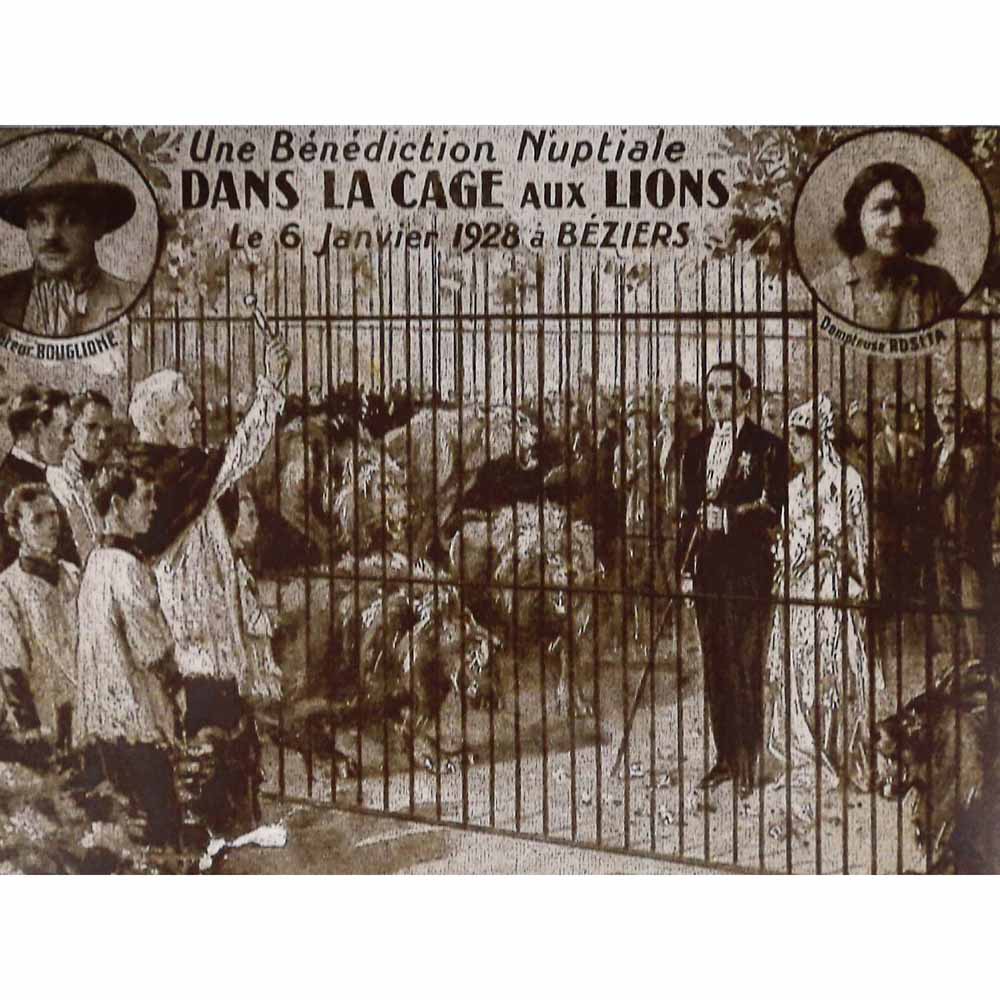

The Menagerie Van Been toured Europe in their horse-drawn Romany caravans with their snakes, bears, apes, lions and elephants. Rosa’s wedding to Joseph Bouglione, a big cat trainer from another circus, took place among the lions and the couple spent their honeymoon traveling with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. Rosa’s reminiscences of a century of circus life are full of eccentric animals, such as Jacky the gorilla who would only drink Perrier water, or the anaconda who squeezed attractive women tighter than others, or Coco, the foul-mouthed parrot who screamed “Help” so loudly he fooled the police. The pelt of Rosa’s pet leopard Mickey remained with her to the end on top of her dining table, seemingly snarling at visitors.

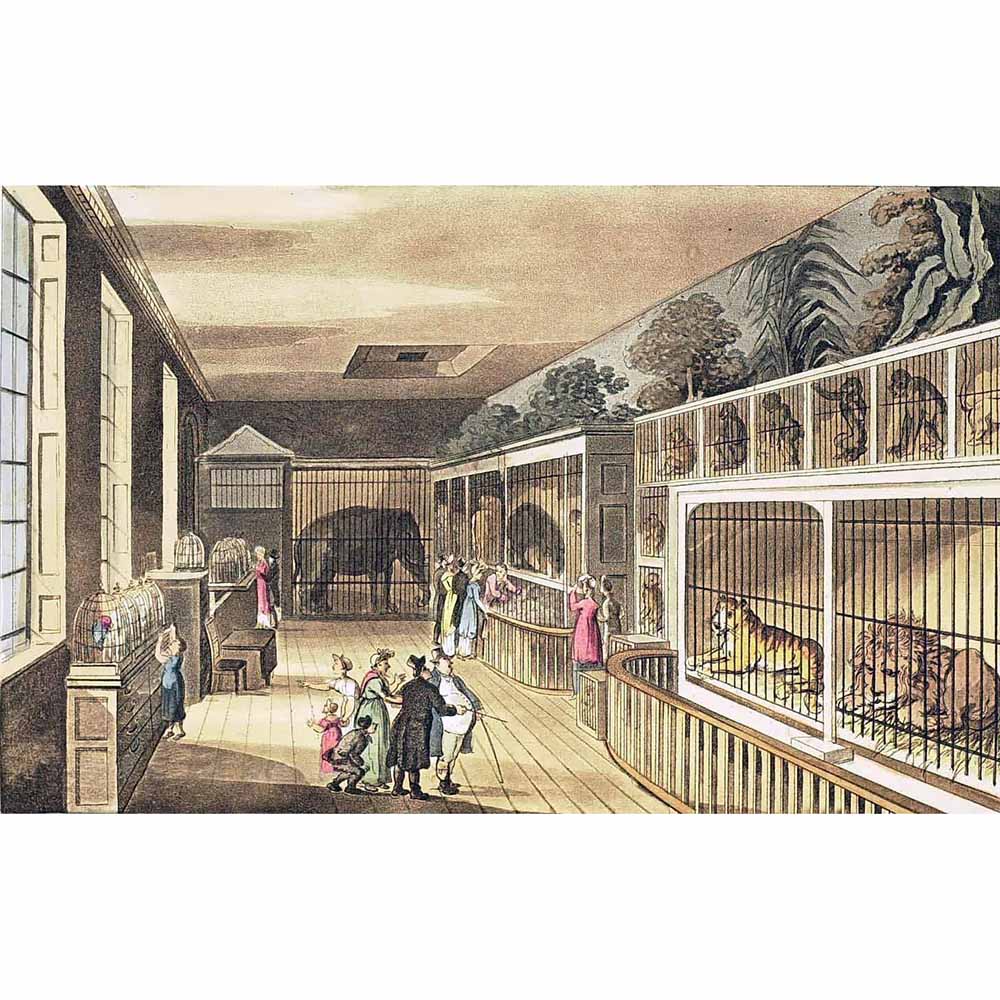

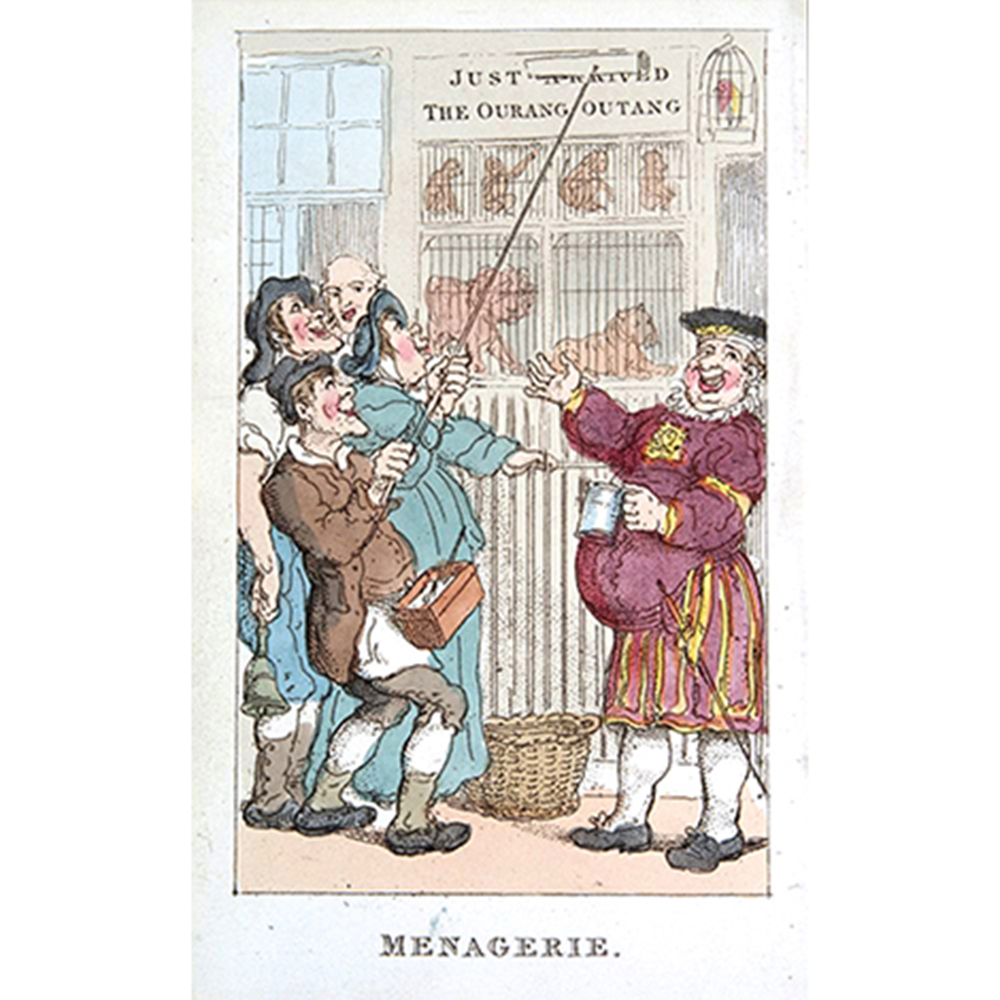

Menagerie shows with exotic beasts have long fascinated the public. For centuries, Londoners flocked to the Tower of London to see the royal collection of animal gifts from foreign lands. The roar of lions resounded in the City of London in 1235, an African elephant arrived in 1255, and a chained polar bear could be seen swimming and fishing in the River Thames. Admission to the Tower Menagerie in the 1700s was three half-pennies or some cats and dogs to feed the hungry lions. In the 1830s, the remaining animals were transferred to the newly opened London Zoo at Regent’s Park.

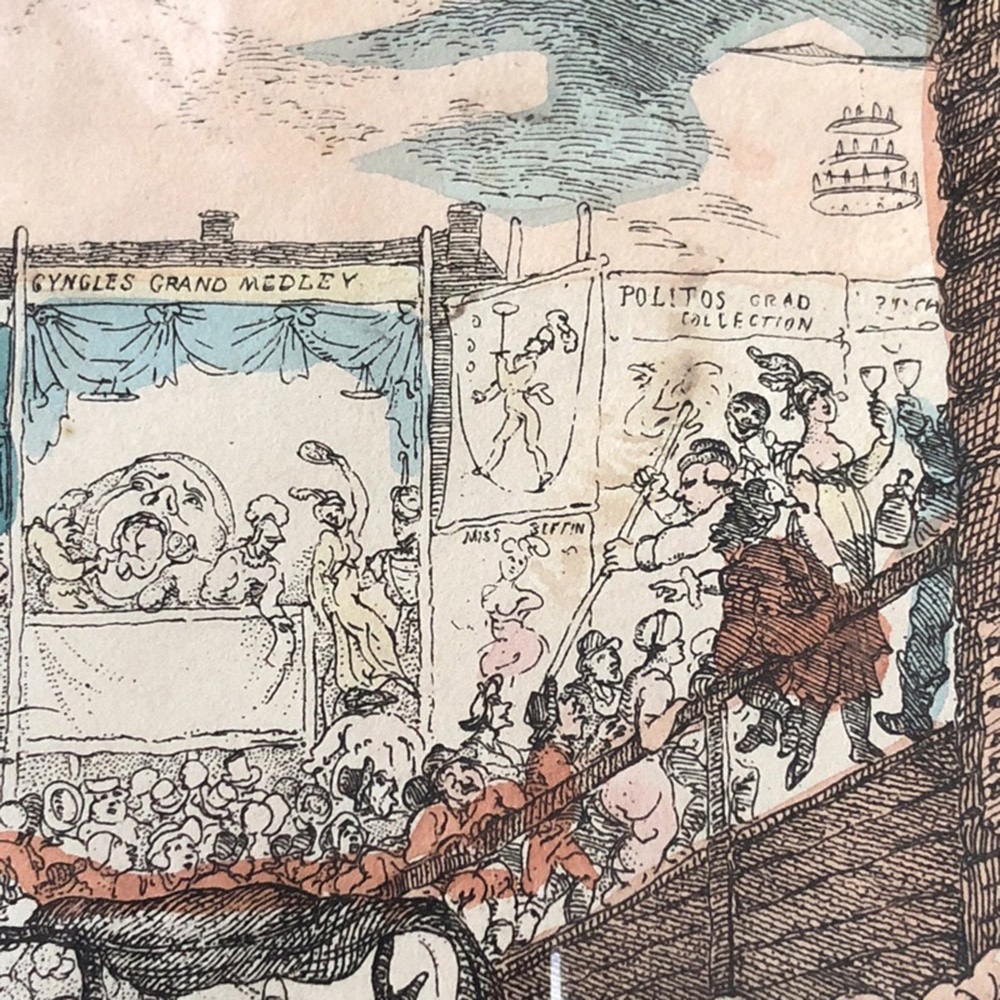

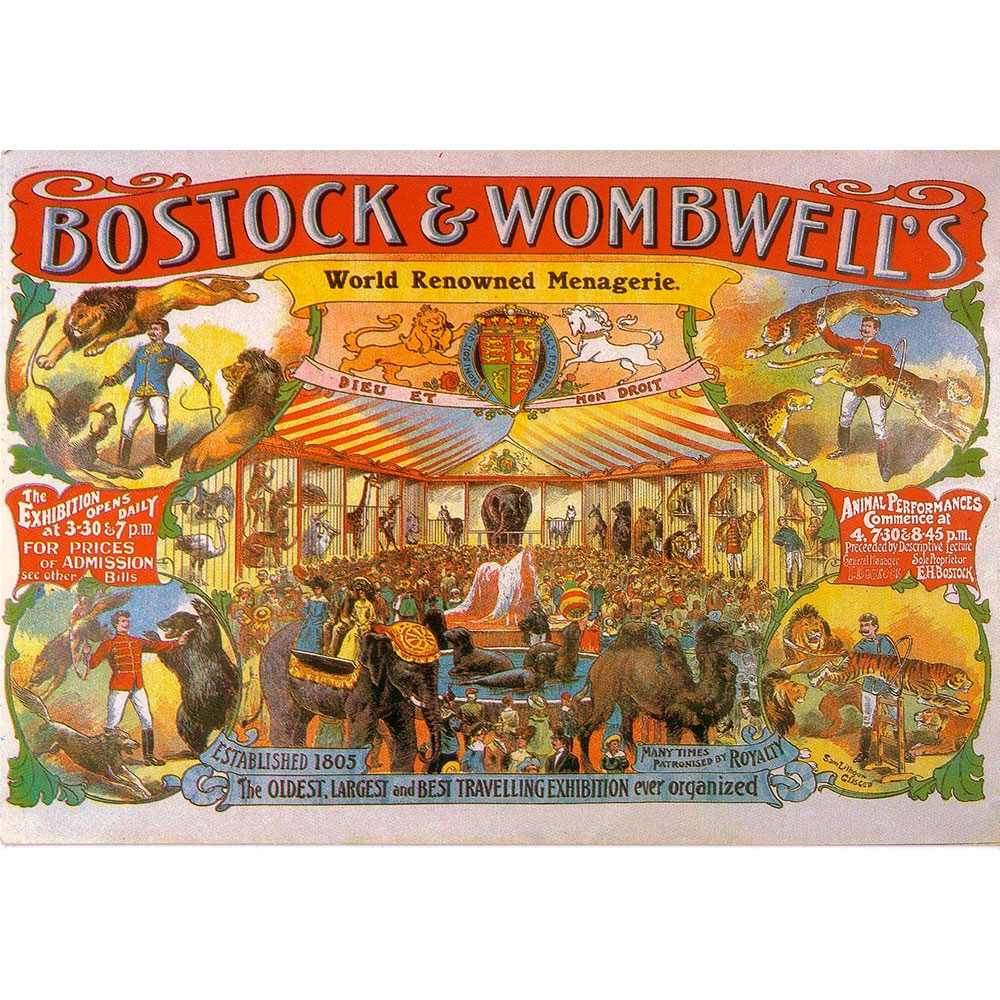

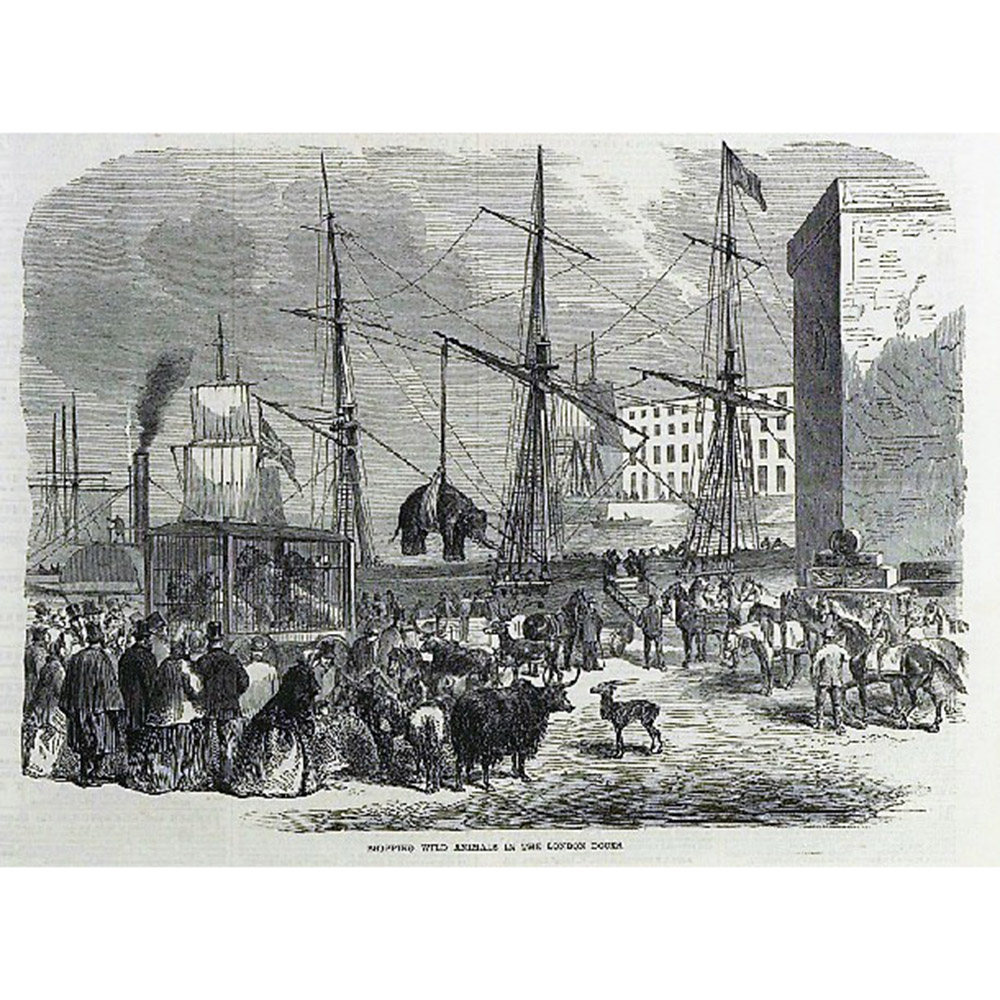

Traveling menagerie shows entertained the rest of Britain in the 18th and 19th centuries. Polito’s Menagerie toured the summer fairs and in winter the lions, tigers, elephants, zebras and kangaroos were exhibited in the Strand, London. Chunee, the elephant, rang a bell to announce feeding time which was the most popular time to view the animals. Wombwell’s Menagerie also toured the country with 15 wagons filled with exotic animals that he purchased from ships arriving in London. He bought the first giraffe to arrive in Britain and a rhino described as the real “unicorn from scripture”. A brass band and sideshows helped to entice the crowds. Wombwell was invited to the royal court on several occasions to exhibit his animals before Queen Victoria. When his elephant died, he put up a sign advertising “The only dead elephant at the fair” and the public clamored to poke the dead beast, realizing that they could see a living elephant at any time. The most famous menagerie elephant was Jumbo, who lived at London Zoo until he was sold to Barnum & Bailey’s circus in America in 1882. His move prompted a public outcry and he was much mourned when he was hit by a train in Canada three years later.

The American animal trainer Isaac Van Amburgh was the first to introduce jungle acts to the circus and paved the way for combining the two forms of public entertainment. The original Lion King began as a cage cleaner at the NY Zoological Institute and became renowned for his daring acts, including putting his head in the jaws of a lion. His menagerie toured Europe also, performing for Queen Victoria, and he became very wealthy, recognizing that “novelty plus publicity means money.” An 1862 report in the New York Times describes a city performance of Van Amburgh’s mammoth menagerie show with loquacious enthusiasm. “The gentle gazelle, the frisky monkey, the spotted leopard, the striped tiger, the noble lion and the sagacious elephant…a pupil of Van Amburgh toys and plays with the beasts as though they were as harmless as kittens.” In his lion-taming acts, Isaac Van Amburgh usually wore a Roman toga reminiscent of gladiators at the Circus Maximus and he is depicted in this garb as a Staffordshire pottery figure in the WMODA collection.

Menagerie shows were such popular entertainments during the 19th century that the Staffordshire potters modeled several earthenware figures of famous performers and animals, perhaps as mementoes of a special day out. The most ambitious are the figurative tableaux depicting menageries with their sideshows. A Pearlware sculpture inscribed “Polito’s Menagerie of the wonderful birds and beasts from most parts of the world” is attributed to Obadiah Sheratt. No doubt George Tinworth, the first artist at Doulton’s studio in London, experienced one of the Victorian Menagerie shows. Perhaps he also knew the Staffordshire sculptures, as they appear to have influenced his unusual Lambeth stoneware clock case. However, instead of humans enjoying the wild beast show, he has substituted nineteen mice. As at Wombwell’s show, a brass band attracts the audience who participate in card tricks and a wheel of fortune. A monkey swings on a tightrope at the entrance to the menagerie and at the side an elephant can be seen helping himself to some apples. Incised designs of a rhino, lions and a hippo decorate the building.

George Tinworth is renowned for his amusing stoneware sculptures of mice engaged in human pursuits. Many were used as menu holders and act as conversation pieces at the dinner table. It is not known what prompted Tinworth to model this extraordinary clock case but perhaps it was a request from Sir Henry Doulton. Three different versions of the Menagerie clock have been recorded with slightly different colorings. One was in the famous Harriman Judd collection in California for many years and was exhibited at the Doulton Story exhibition in 1979 before being loaned to the LA county museum. It was sold at Sotheby’s of New York in 2001. WMODA is grateful to Don Kendall of Texas for enabling us to show this spectacular piece in our Carnival & Cabaret exhibit.

Menagerie Clock G. Tinworth from Don Kendall

Menagerie Clock G. Tinworth from Don Kendall

Menagerie Clock G. Tinworth from Don Kendall

Menagerie Clock G. Tinworth from Don Kendall

Menagerie Clock G. Tinworth from Don Kendall

Menagerie Clock G. Tinworth from Don Kendall

Menagerie Clock G. Tinworth from Don Kendall

Menagerie Clock G. Tinworth from Don Kendall

Photo Courtesy of Christies