By Louise Irvine

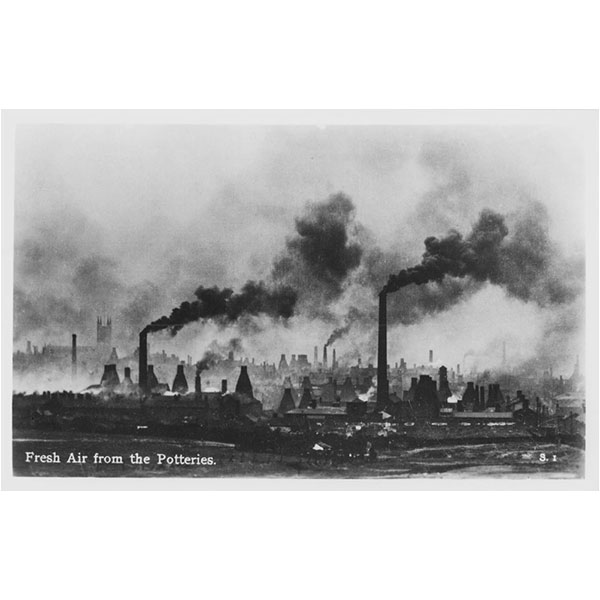

The most famous image of smoky Stoke is entitled Fresh Air for the Potteries, but the air was anything but fresh, as can be seen in the work of the American-born photographer William Blake. He recorded local Potteries life for 50 years and his photographs can be enjoyed at the Potteries Museum & Art Gallery in England and in an online exhibition. We are also exploring the influence of his images at WMODA.

William Blake was born in Pittsburgh in 1874, and his mother returned to England with him when his father died. The family eventually moved to Longton, one of the six Potteries towns, where William opened a stationery business. A talented photographer, he captured scenes of working life and social conditions among the potbanks and sold many as postcards in his shop.

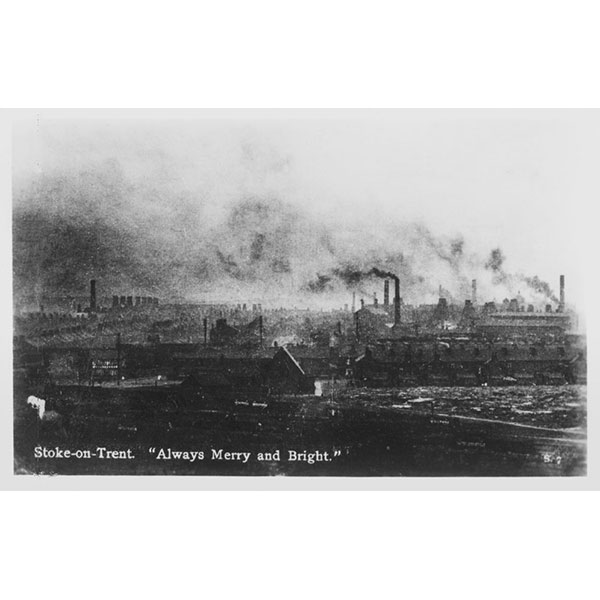

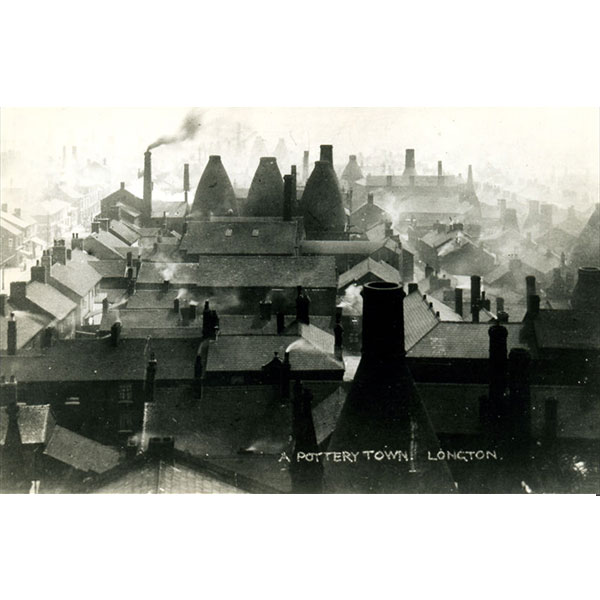

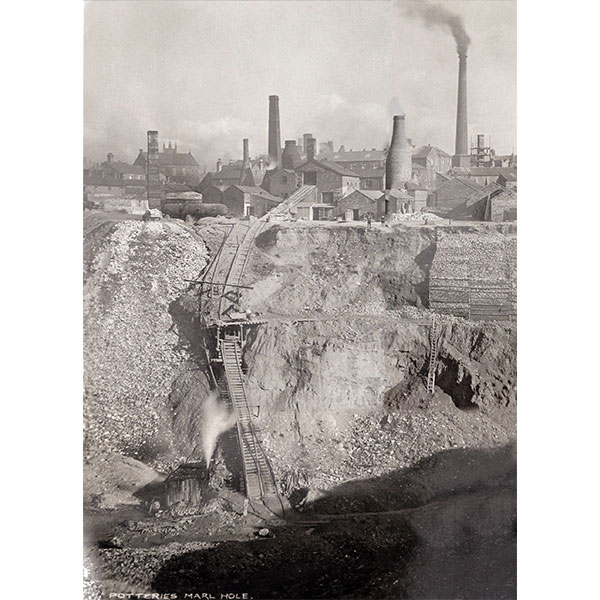

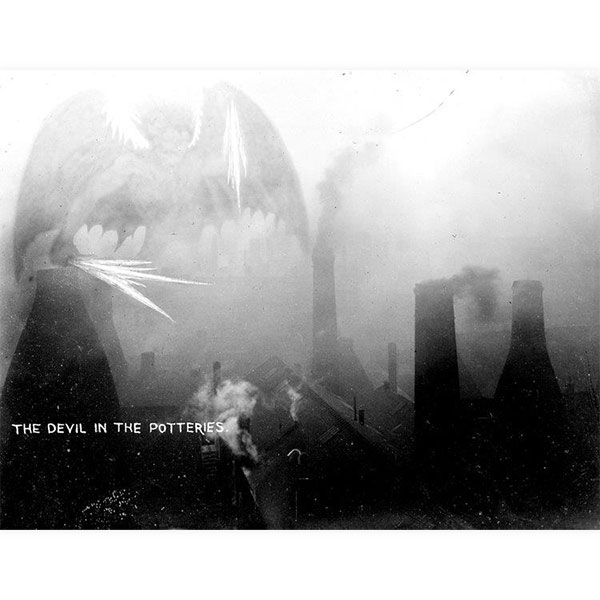

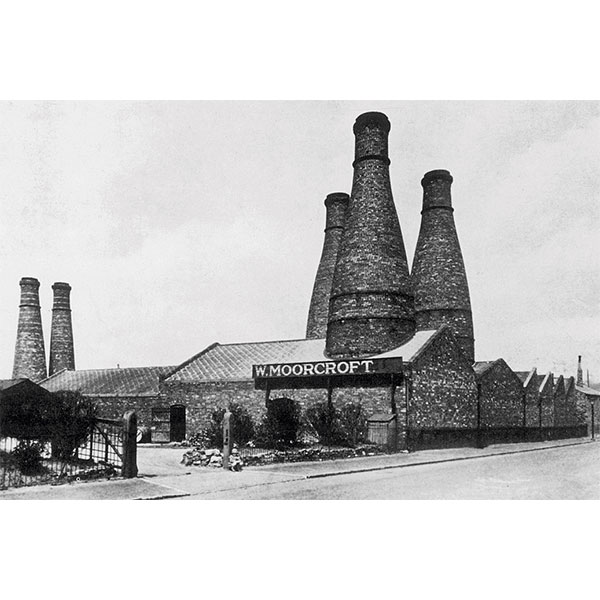

In the early 1900s, postcards were the text messages of their time. Images of local events could be printed in a day. Sending them was cheap and convenient as mail was collected and delivered up to 12 times daily in large cities. The postcard craze peaked in the Edwardian era, with billions sent yearly. Blake’s black and white negatives of Potteries views were popular with local postcard publishers, such as Shaw of Burslem, who printed high-quality cards in Germany. His best-known postcards were the “Smokies,” which depicted the smoking industrial landscape of bottle ovens and marl pits with ironic captions such as “Always Merry and Bright.”

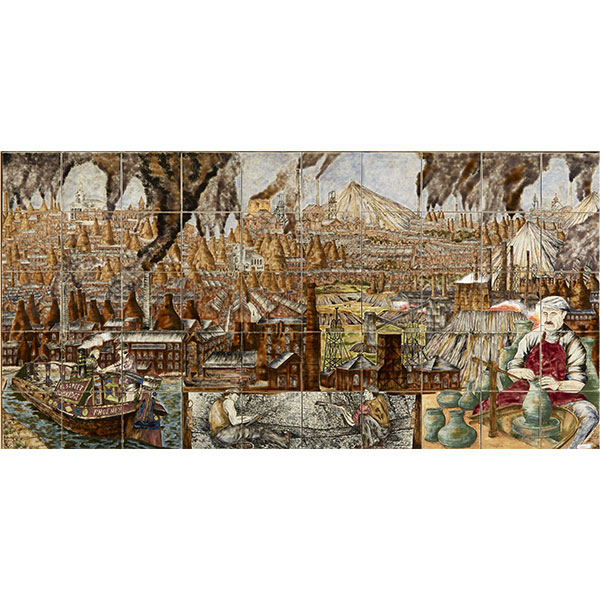

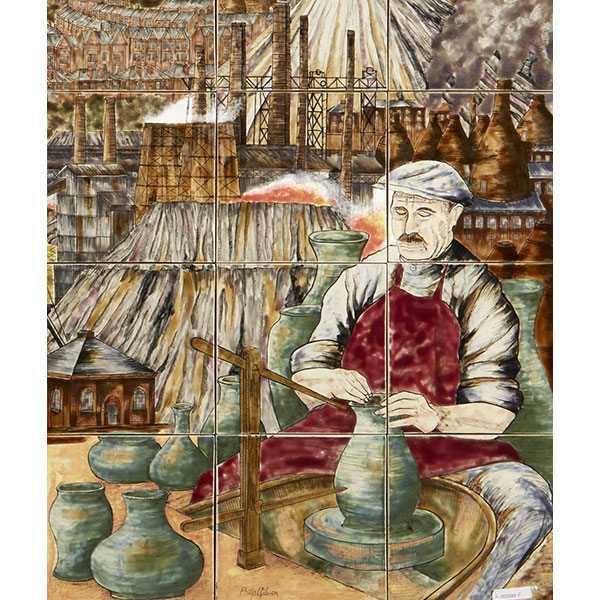

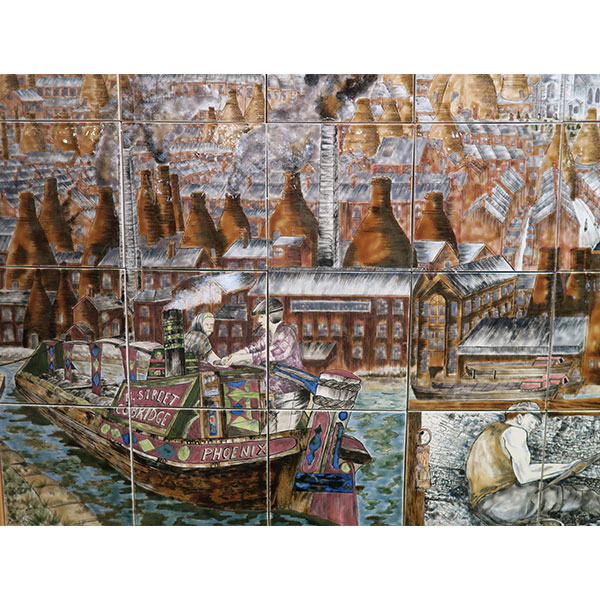

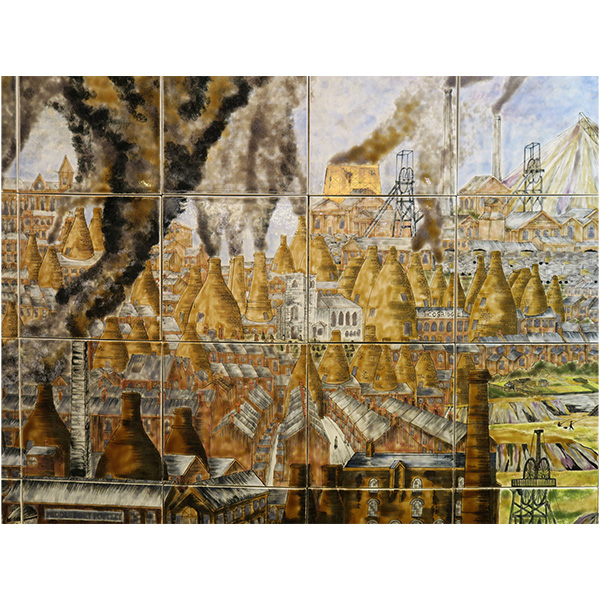

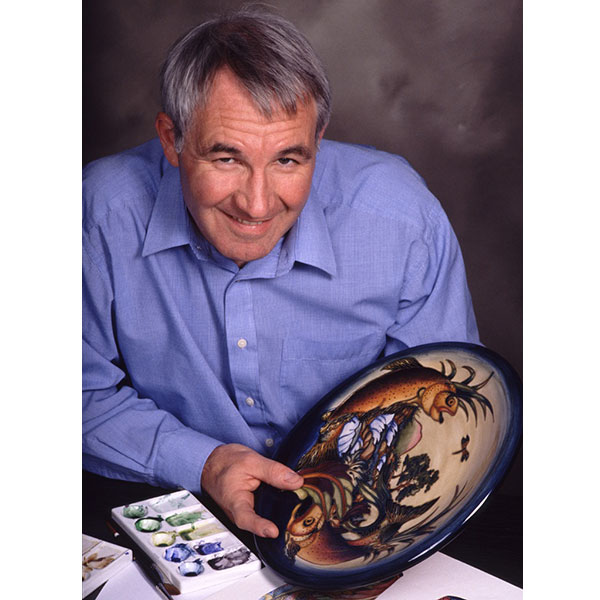

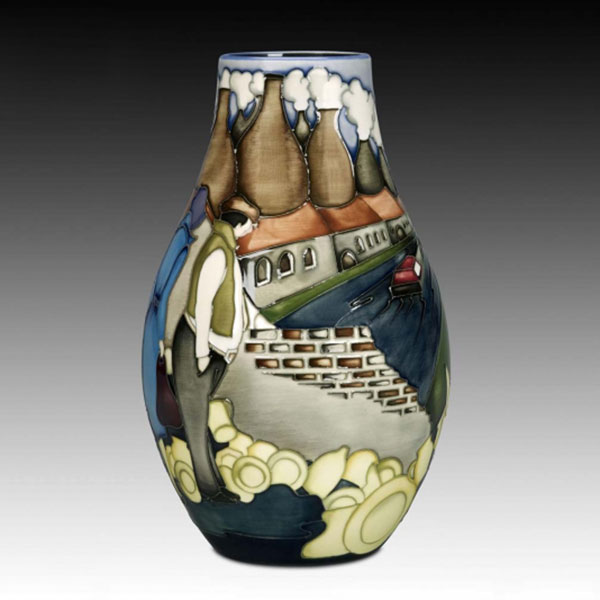

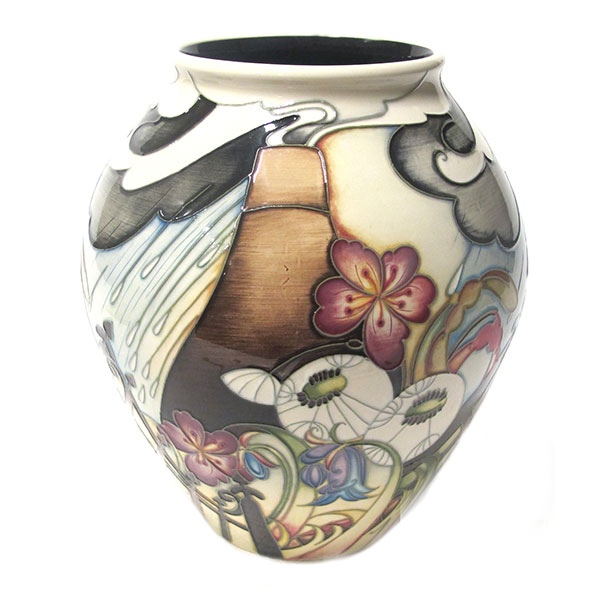

Smoky Stoke can be seen in the Cobridge Stoneware tile mural at WMODA, which depicts the Staffordshire Potteries in prosperous times and celebrates the local industries, including the back-breaking work of the coal miners and the skill of the potter on his wheel. Designer Philip Gibson grew up in the area and remembers how thick smoke and grime from the bottle kilns darkened the sky, and in the evening, there was a red glow from the blast furnaces of the steel works. Working from childhood memories and archive photographs, Philip has portrayed the modest streets of terrace houses among thousands of coal-fired bottle kilns, which dominated the skyline of the Potteries in the 19th century. He also designed a vase featuring smoky Stoke for Cobridge Stoneware.

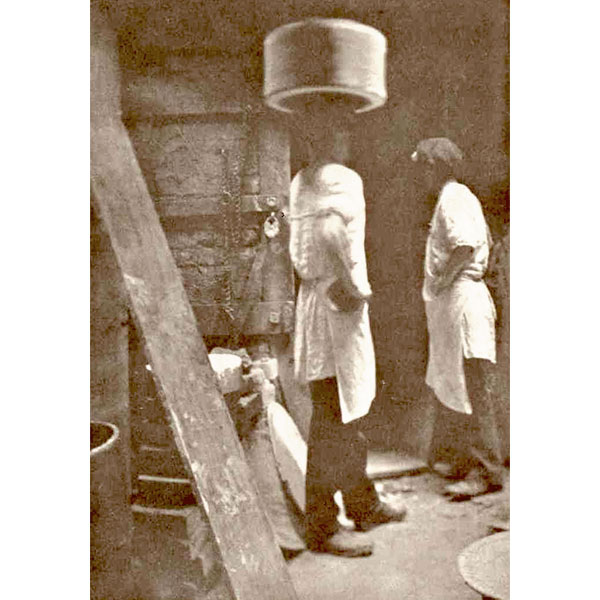

Around 4,000 bottle kilns were in operation by the early 1900s, and each firing took 14 tons of coal. The firemouths were baited every four hours to reach a temperature of 1250 degrees centigrade. Flames rose inside the kiln, and heat passed between containers full of unfired green ware known as saggars, which safeguarded the pieces from the direct heat and gases during firing. One of Blake’s postcards shows two saggar makers in their pot bank workshop. They rolled fireclay around a wooden form, and a young lad beat the clay into a metal ring to make the bottom. He was amusingly known as the saggar maker’s bottom knocker!

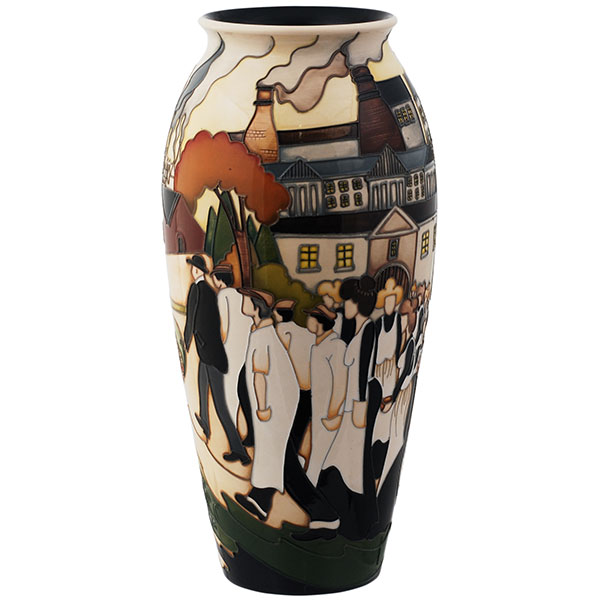

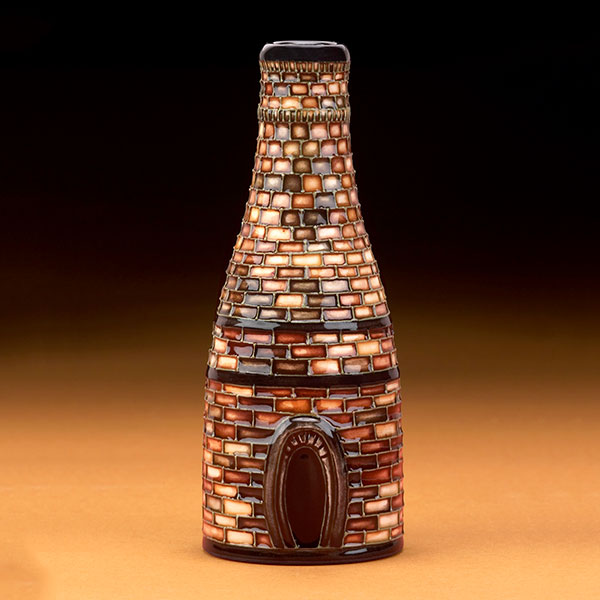

Coal firing was inefficient, with about 90 % of the fuel energy going up in smoke. Gradually, the bottle ovens were replaced by gas and electric tunnel kilns, and by the 1950s, only 2,000 bottle kilns were still in use. Following the Clean Air Act in 1956, only 47 remain, with some preserved as listed buildings in museums. The Moorcroft Pottery in Cobridge still has one of its original bottle kilns in its Heritage Visitor Centre, and the design studio artists have portrayed this iconic landmark in several vases celebrating the company’s history. To mark the 100th anniversary of their factory in 2013, Paul Hilditch designed the William at Work vase, which depicts different stages in the pottery process, including wheel throwing, decorating and kiln placing.

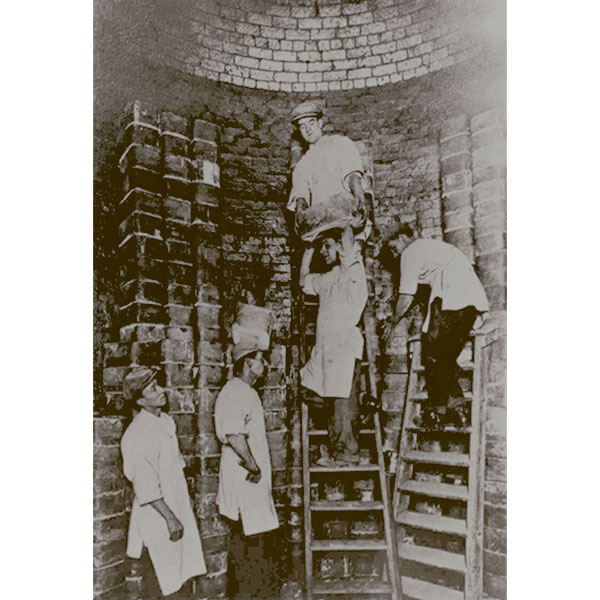

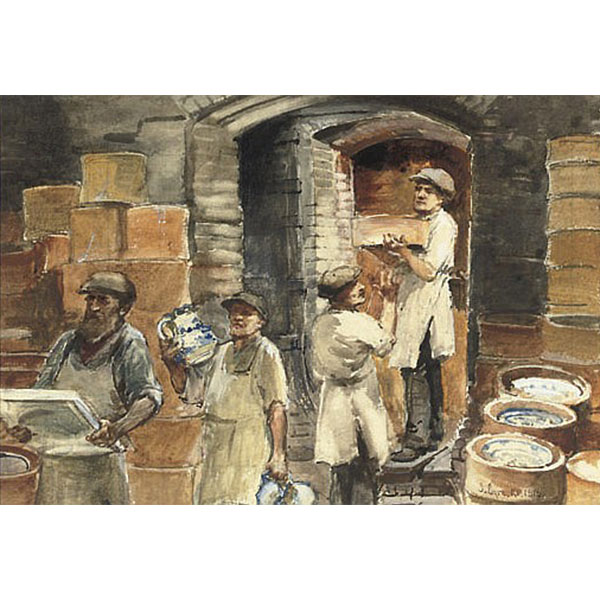

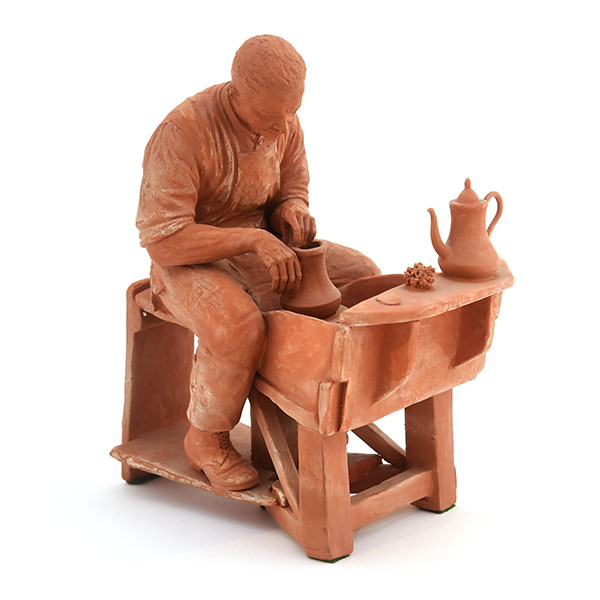

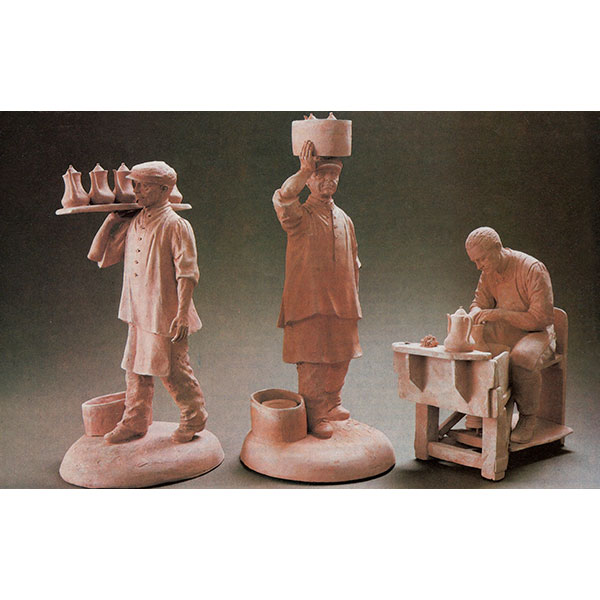

Each saggar was filled with vases, teapots, and cups embedded in layers of flint and weighed around 55 pounds. The kiln placers balanced the saggars on their heads as they climbed ladders to stack tall columns inside the kiln. Their skill was recorded for posterity by Peggy Davies, a figurine sculptor for Royal Doulton, who made a series of terracotta figures featuring the traditional industries of the Potteries. Her kiln placer, coal miner and thrower figures can be seen in the new display at WMODA.

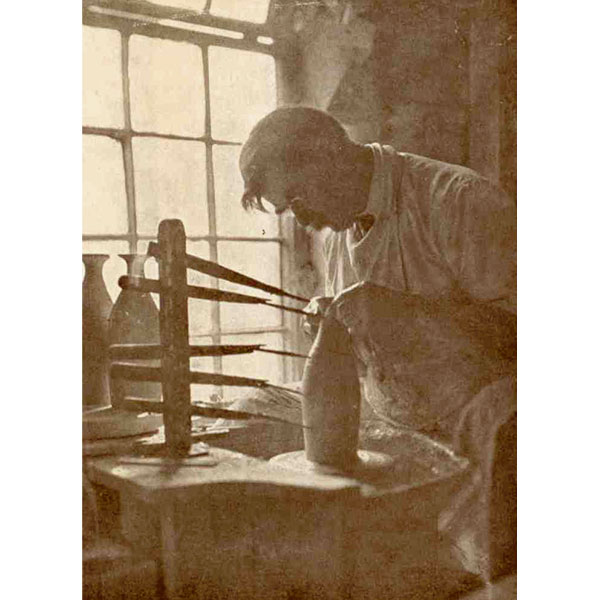

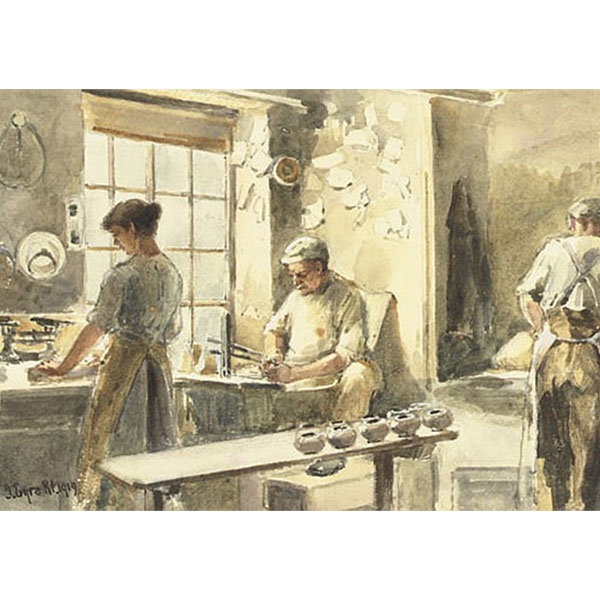

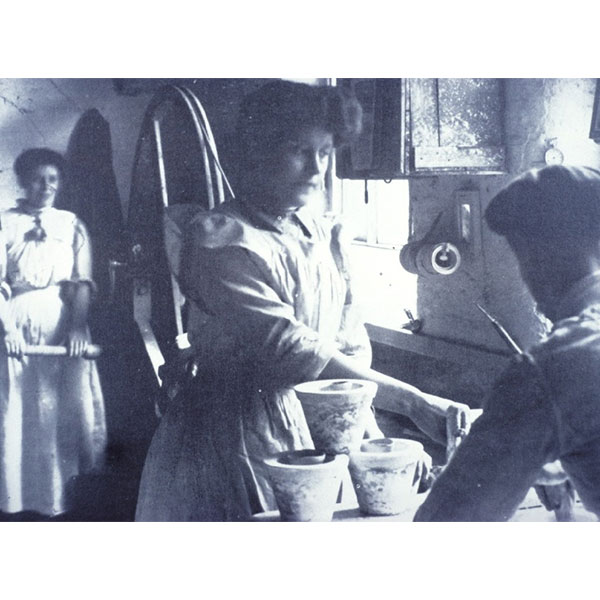

William Blake took photographs of potters at work in different factories for his postcards and for a lantern slide presentation that he gave in the early 1900s about Staffordshire Pottery. His photographic archive includes images of many different pottery skills, including casters, dippers, cup handlers, painters, and throwers. To “throw” a pot derives from Old English, meaning to twist and turn, and skilled throwers have been portrayed on Moorcroft vases, Royal Doulton figurines, and the Cobridge tile panel, which can be seen at WMODA. When the museum reopens, live wheel-throwing demonstrations by local potters will resume at special events as we celebrate the traditional skills of the Potteries.

Photo credit: Potteries Museum and Art Gallery

Read more about the William Blake exhibition in Stoke-on-Trent

Read more about the Potteries tile panel at WMODA

Moorcroft Chimney Smoke Trial Vase

Always Merry and Bright Postcard W. Blake

Firing a Potters Oven Postcard W. Blake

Fresh Air from the Potteries Postcard W. Blake

Longton Postcard W. Blake

Marl Pit Daisy Bank Postcard W. Blake

Devil in the Potteries Postcard W. Blake

Cobridge Stoneware Potteries Panel

Potter at Wheel Detail

Middleport Detail

Bottle Kilns Detail

Cobridge Stoneware Vase

Philiip Gibson

Moorcroft Brindley's Canal K. Goodwin

Moorcroft The Walk Vase K. Goodwin

Moorcroft William at Work P. Hilditch

Moorcroft Bottle Kiln Smoking Trial Vase

Moorcroft Bottle Kiln R. Tabbenor

Moorcroft Bottle Kiln

Moorcroft Factory Bottle Kilns

Kiln Placer Peggy Davies

Kiln Placers Royal Doulton

Kiln Placers

Loading Kiln J. Eyre

Saggar Making Postcard W. Blake

Royal Doulton Potter Prototype E. Griffiths

Royal Doulton Thrower

Thrower J. Eyre

Thrower's Assistants

Thrower P. Davies

Staffordshire Industries P. Davies

Moorcroft William at Work Throwing P. Hilditch

Ellen Cohen Berman

Alex Meiklejohn