By Louise Irvine

The American Ceramic Circle conference will be held in St. Louis this year and Louise Irvine has been invited to talk about Royal Doulton art pottery displayed at the World’s Fairs in America. The Louisiana Purchase Exposition held in St. Louis was the biggest event in the world in 1904 and it is well-known from the 1944 musical movie starring Judy Garland. Meet Louise in St. Louis at the ACC conference from October 23 to 25.

Louise Irvine with Doulton's Maharaja Vase at WMODA

Meet Me In St. Louis Movie Poster

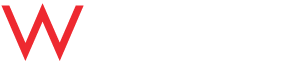

St. Louis World's Fair Postcard

Novel ice cream cones in St. Louis

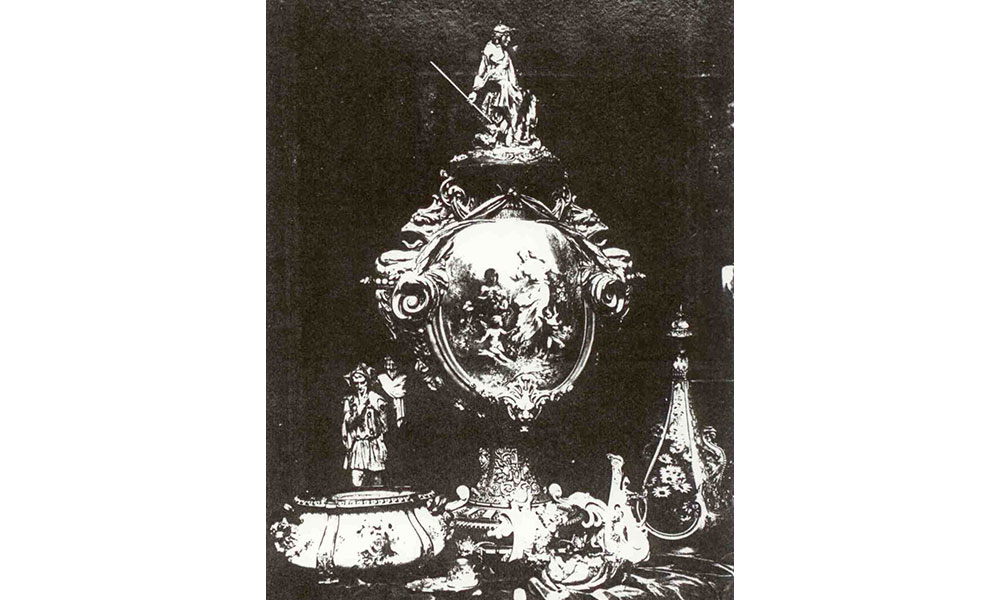

International exhibitions were huge events during the 19th century, and it is hard to imagine their enormous impact in the days before television and radio. The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, held in 1851 at the Crystal Palace in London, was the first truly international event showcasing design and manufacturing from 32 countries. The 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, was the first official World’s Fair in America. It spanned 236 acres and featured 37 countries. The Chicago Exhibition in 1893 marked the 400th anniversary of the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the New World. The scale and grandeur of this exposition were unprecedented, with 200 buildings featuring 46 countries on the 660-acre site, which became known as the White City.

Doulton Lambeth Vase by F. Butler

Doulton's Display at the Philadelphia World's Fair

Doulton Exhibit in Philadelphia

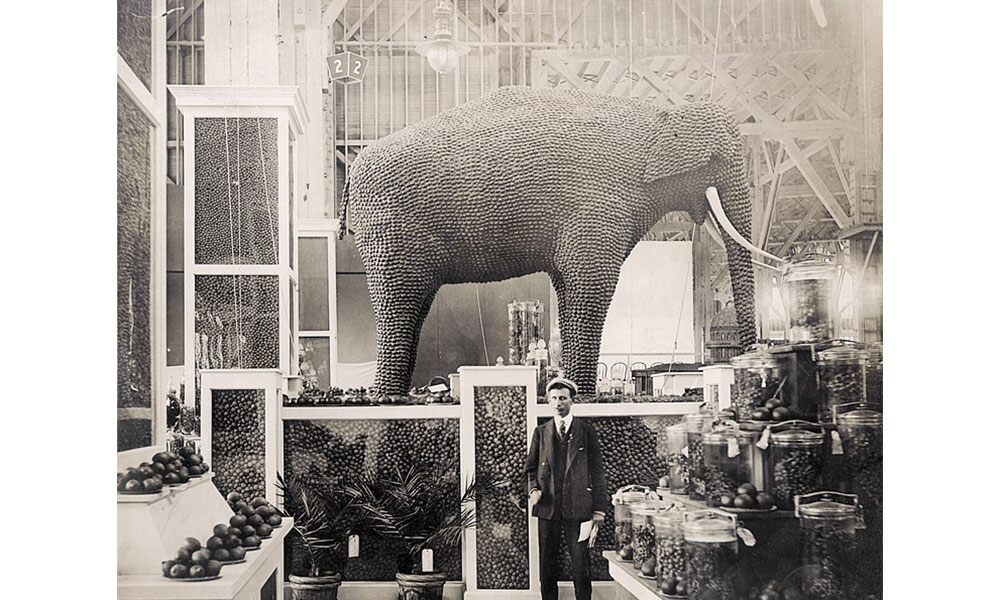

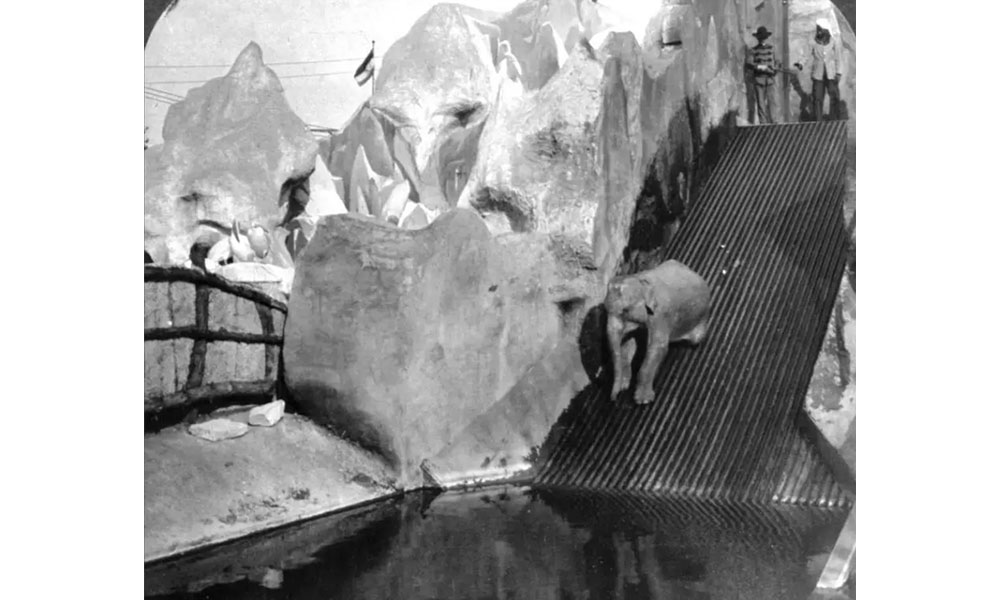

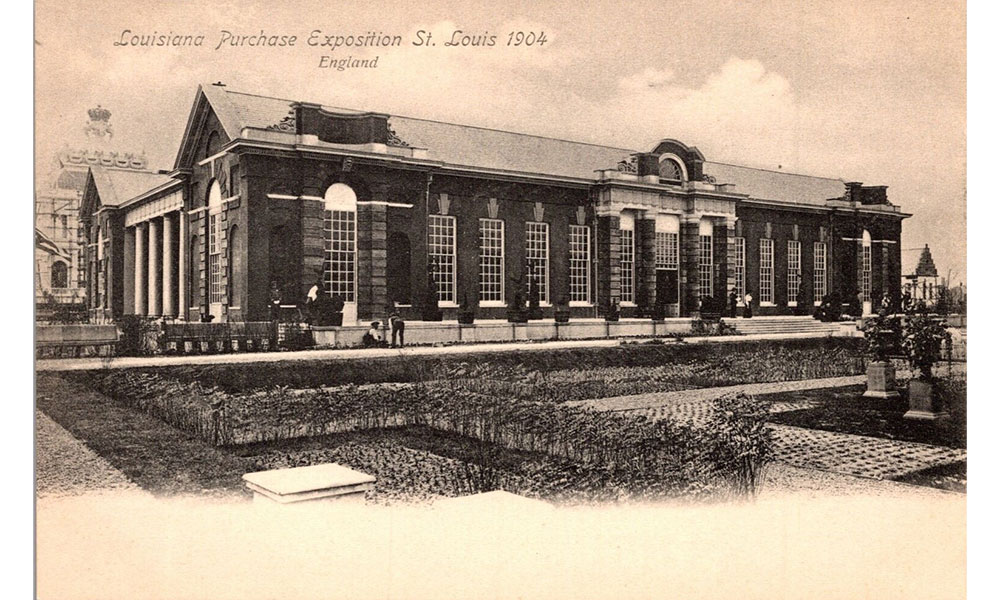

The 1904 St. Louis Exhibition commemorated the centenary of the purchase of Louisiana from the French by the United States. It was intended to eclipse all previous events and was the largest-ever World’s Fair. The site covered 1,240 acres with over 1,500 buildings. Nearly 20 million people visited during the 8-month run to see exhibits from 60 countries and 43 of the then 45 states. For most visitors, the fair was about entertainment, popular culture, new foods and consumer goods. Iced tea and ice cream cones were popularized during the hot weather at this event. The public marveled at the elephant made from nuts presented by California in the Palace of Horticulture and watched Carl Hagenbeck’s trained elephant “shooting the chutes” in the wild animal enclosures.

Doulton Mermaid Centerpiece for Chicago by C.J. Noke

Doulton Christopher Columbus by C.J. Noke

Bleu Royale Vase for Chicago by G. White

Doulton Exhibit in Chicago

Doulton's Chicago Exhibits including the Diana Vase

Chicago World's Fair

Chicago World's Fair Poster

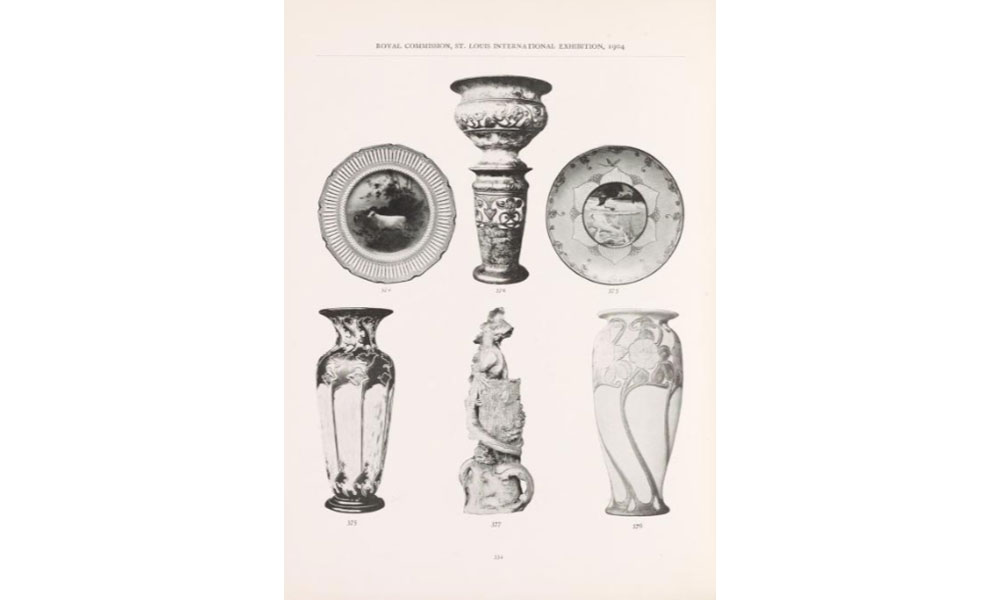

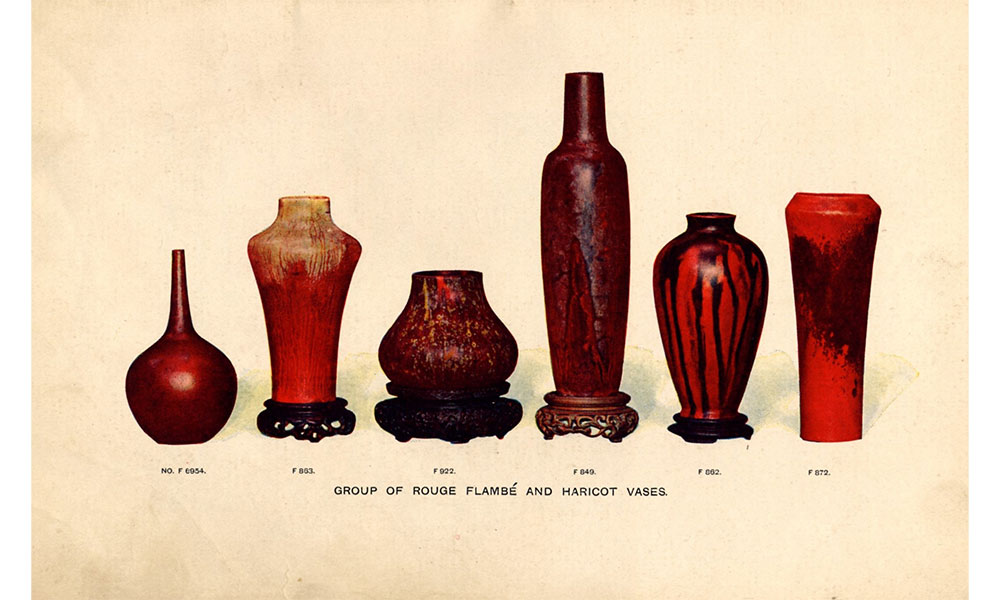

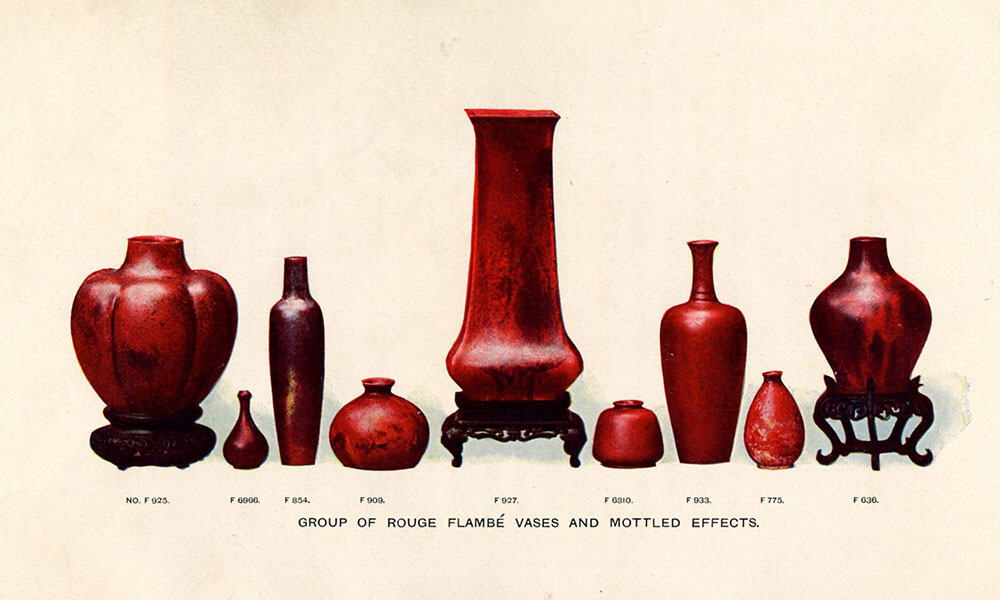

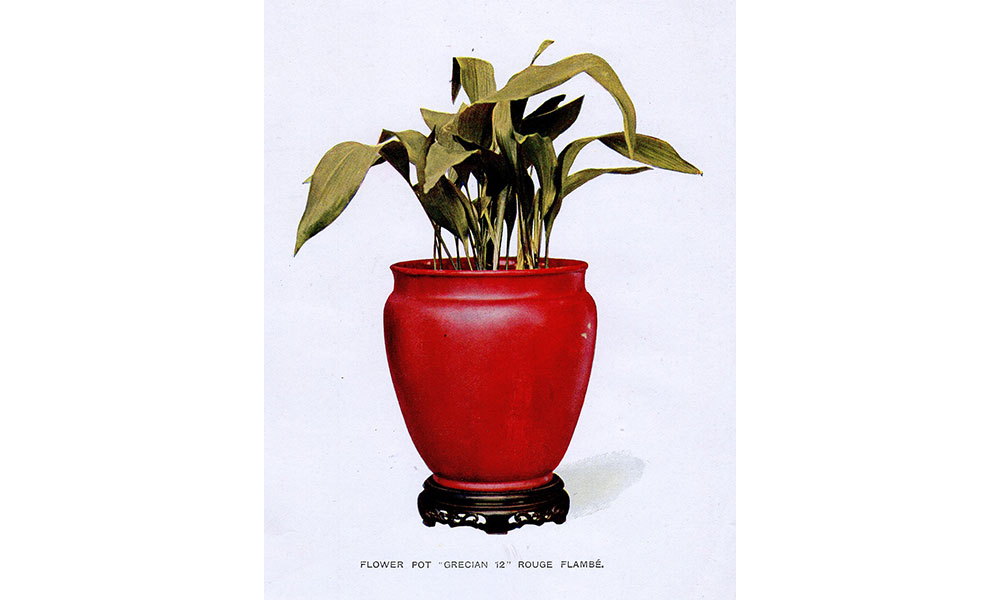

The fair was also an important stage for British potteries, which showcased their latest innovations. Established companies, such as Royal Doulton and Minton, were awarded Grand Prizes for their exhibits alongside a relative newcomer, the Ruskin Pottery. Most manufacturers showed together in the British section, but Royal Doulton took an independent stand 40 feet by 40 feet, anticipating the success of their experimental rouge flambé glazes. Their initiative paid off, and they won 30 awards, including 3 Grand Prizes, 4 gold, and 23 bronze medals. All their exhibits were sold at the fair despite high duties on imported china and 25% commission to the Exposition treasury.

Walnut Elephant St. Louis

Hagenbeck’s elephant “shooting the chutes"

Britain & Ireland with Royal Doulton Stand

St. Louis Grand Prize

England Pavilion St. Louis Postcard

George Tinworth, Doulton’s “evangelist in art” received a Grand Prize for his massive terracotta panel depicting Christ’s Kingdom of Peace, which measured 15 feet by 5 feet. Doulton also provided a terracotta fountain, sundial, urns and parapets for the gardens of the British Commission House. Doulton’s Lambeth Studio displayed stoneware sculptures and vases by leading artists, such as Mark Marshall, Francis Pope and John Broad, who were all awarded bronze medals. Lambeth Faience ware had a new look due to the introduction of leadless glazes in 1900. Art Nouveau style maidens painted by Margaret Thompson and John McLennan won them both bronze medals.

Royal Doulton Highlights at St. Louis

Doulton Lambeth Faience Maidens by M. Thompson

Doulton Lambeth Faience Evening by J. McLennan

Doulton Lambeth Faience Rose Fairies by J. McLennan

Doulton Lambeth Grotesque Reptile by M. V. Marshall

Doulton Archive Photo of Reptile on Rock

Royal Doulton Jardiniere and Stand by F. Pope

John McLennan in Doulton Studio

Mark Marshall

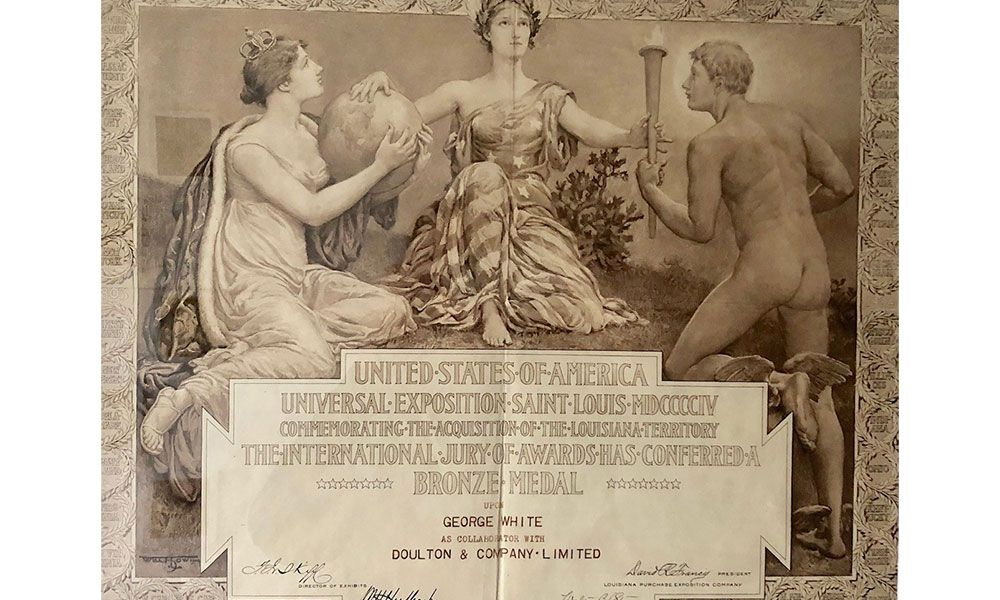

There were also several bronze medalists from the Burslem Studio, including Charles Beresford Hopkins, who painted the magnificent Pastoral vase now at WMODA. Charles Noke, Burslem’s Art Director, was awarded a gold medal for his studio’s contribution to the exhibition. His notebook lists the bone china and earthenware exhibits for St. Louis, including flower vases, centerpieces, tea wares, assorted fish, game and dessert services, umbrella stands, tobacco jars and toilet sets. A new version of the Dante vase, which debuted in Chicago, was painted by George White for the occasion. Noke also displayed a selection of his new Vellum figures, including his iconic Jester.

Royal Doulton Harrowby Plate by C. B. Hopkins

Royal Doulton Pastoral Vase by C. B. Hopkins

Royal Doulton Dante Vase by G. White

Royal Doulton Vellum Jester by C.J. Noke

St. Louis Medal Certificate for George White

Royal Doulton Vellum Jester by C.J. Noke

Royal Doulton Vellum Jester by C.J. Noke

The exhibit that attracted the most attention in the British press as Royal Doulton’s revival of “rouge flambé” and “sang de boeuf” glazes inspired by the “ancient potters of China.” It took Doulton many years of experimentation with the expertise of Bernard Moore to achieve success with their glowing ruby glazes at the St. Louis Exhibition, where they were acclaimed as a “Discovery of a Lost Art.”

Royal Doulton Flambe Wares

Royal Doulton Flambe Wares

Royal Doulton Flambe Flower Pot

Royal Doulton Flambe Coffee Pot

Read more about the American Ceramic Circle conference in St. Louis

Read more about Doulton at the World’s Fairs

Doulton at Chicago World’s Fair | Wiener Museum

World Expo Wares at WMODA | Wiener Museum

World Expo Wares at WMODA | Wiener Museum