As we prepare for our Fantastique exhibition at WMODA, we are discovering how mask-wearing has retained its appeal from ancient Greek theater via the Venetian Carnival and decadent cabarets of Europe to the Halloween parties of today. The word mask descends from the old French masque, meaning a face covering. A masque also became a courtly entertainment involving pantomimes, dancing and acting.

The laughing and weeping masks representing comedy and tragedy are symbols of the classical muses – Thalia was the muse of comedy while Melpomene was the muse of tragedy. Mask motifs from ancient Greek drama can be found on many Neo-classical pottery and porcelain pieces in the WMODA collection

Mask wearing became a feature of Venice’s Carnival season, which can be traced back to the 11th century and was well established by 1436 when mask makers or mascereri were officially recognized with their own guild. Wearing disguises in the streets of Venice and to social gatherings was encouraged for many months of the year and provided a release from the strict moral codes of public behavior instigated by the city council. Sumptuary laws restricted the excessive display of wealth, which could be disguised by the traditional black silk cape, known as a domino, and tricorn hat. The mask also helped equalize social differences and enabled sexual freedoms.

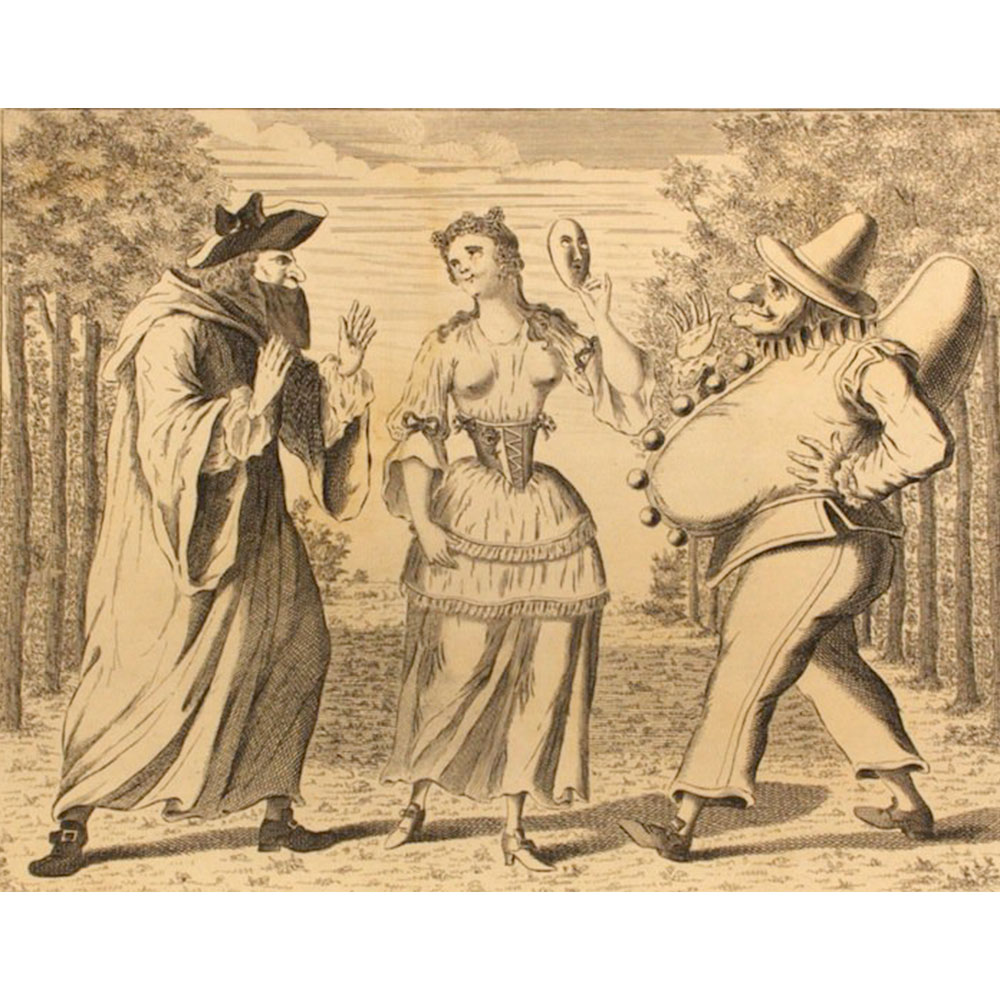

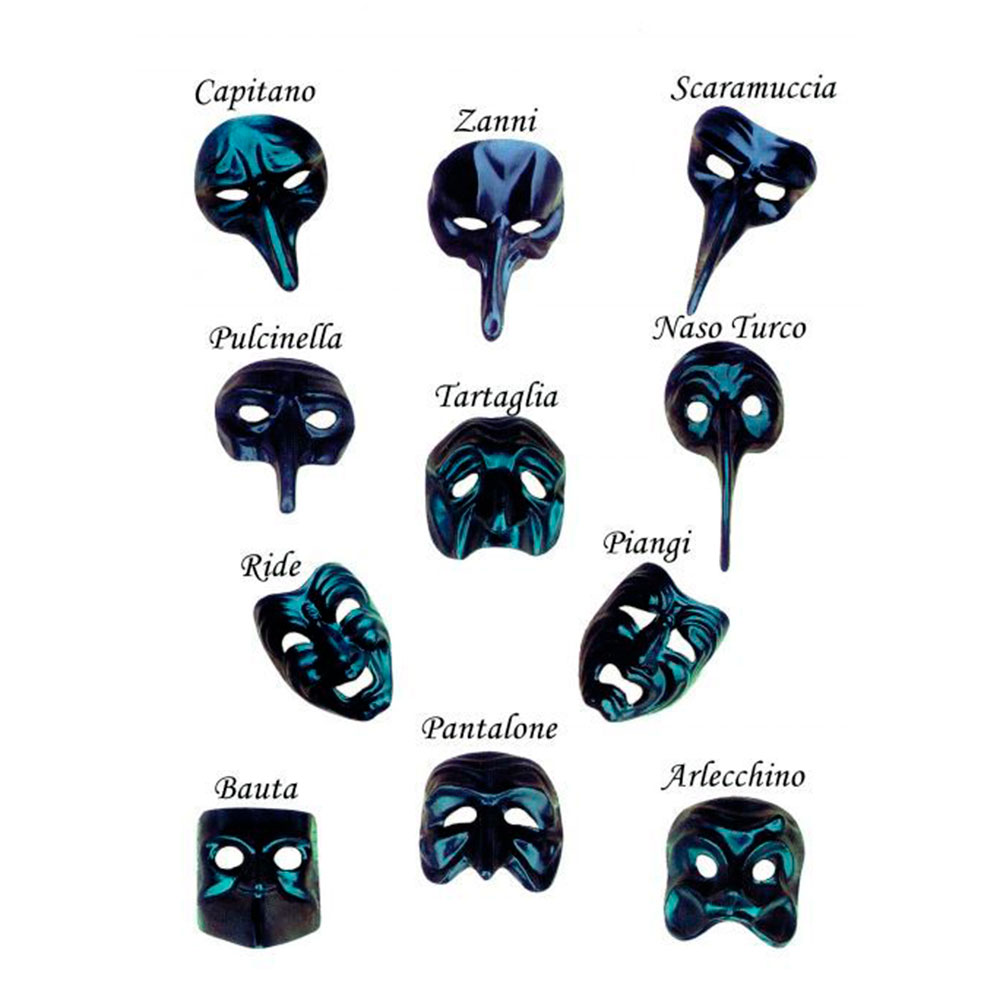

Casanova’s Venice of the 18th century became the pleasure capital of Europe with its carnival, courtesans and casinos. The fall of the Venetian republic put an end to all this frivolity but the 20th century revival of Carnevale has ensured the continued fascination with traditional Venetian masks. Distinct forms, including the Bauta and the Plague Doctor, are on display in our Carnival & Cabaret exhibition, courtesy of Balocoloc Artisans of Venice. Many Venetian masks, such as Arlechino and Columbina, are derived from the Italian commedia dell’arte, the improvised street theater with masked performers which was a huge influence on European entertainments during the Renaissance era.

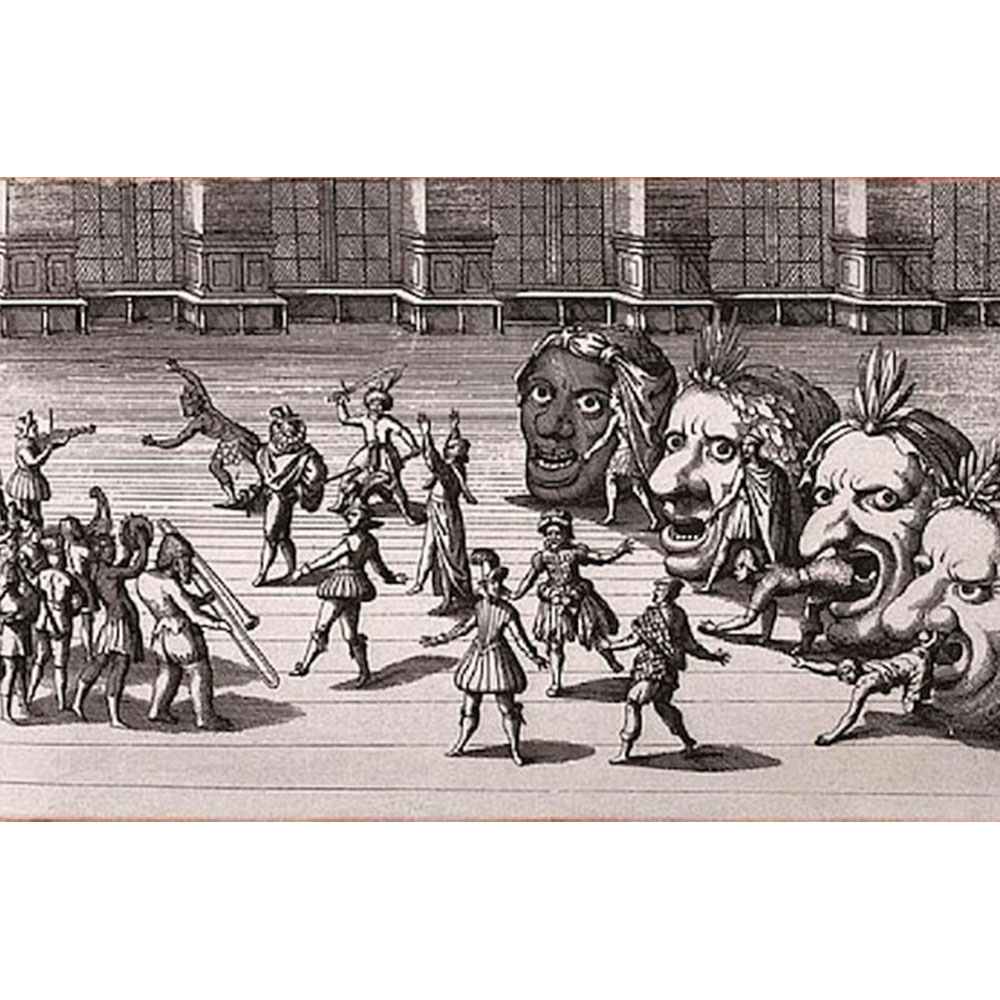

In Tudor England, extravagant court masques became fashionable during the reigns of King Henry VIII and Queen Elizabeth I. These lavish, dramatic entertainments were commissioned from famous dramatists of the era and performed by masked players representing mythological or allegorical figures. Masked ladies of the court often took part in these opulent occasions to show off their singing and dancing skills. Masques were also a feature of royal progresses and the spectacular pageants given when European monarchs made a formal entry into a town. When traveling, wealthy Elizabethan women wore velvet visards to cover their delicate visages from the sun. Although decidedly creepy, these masks were a high fashion accessory in France and England until the 17th century.

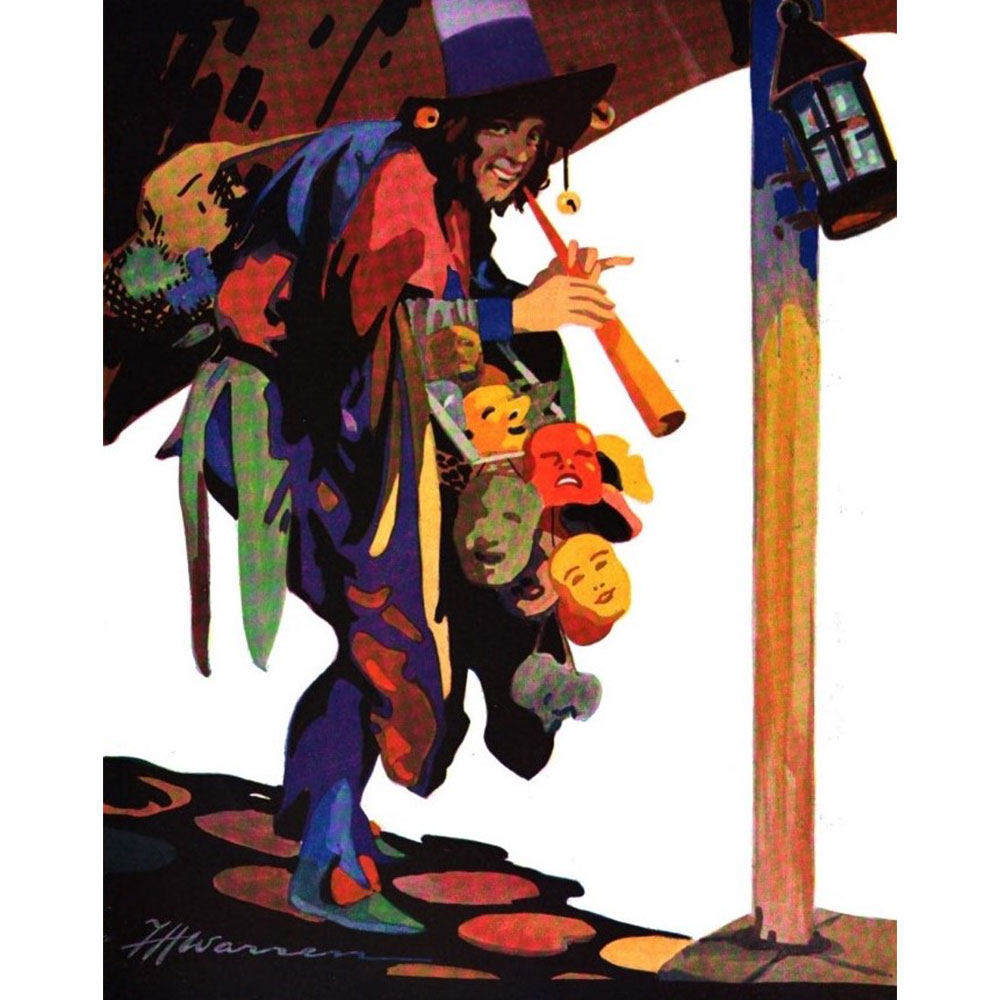

Mask-wearing in England was not confined to the aristocracy and can be traced back to Medieval folk dramas, which included dancers wearing masks portraying animals and human characters. Churches staged dramatized versions of biblical events, known as liturgical dramas, to enliven annual celebrations. These morality plays reinforced the conflict between good and evil for the audience by alternating comic slapstick scenes with serious tragic ones. Villagers would gather in masks and costumes to take part in elaborate processions to mark festivals and holidays. Mummings and disguisings were popular entertainments during the Christmas season. A medieval Mask Seller was depicted by Leslie Harradine for Royal Doulton, after an illustration by F.H. Warren.

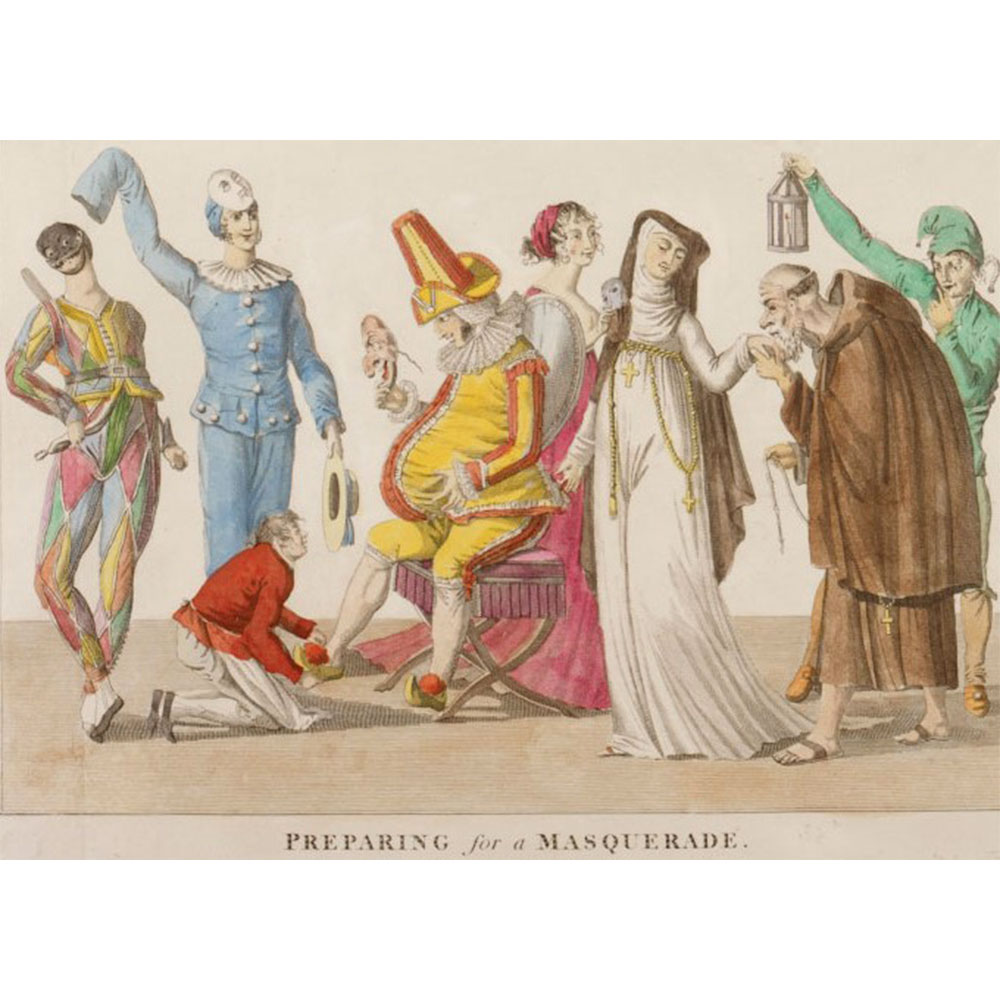

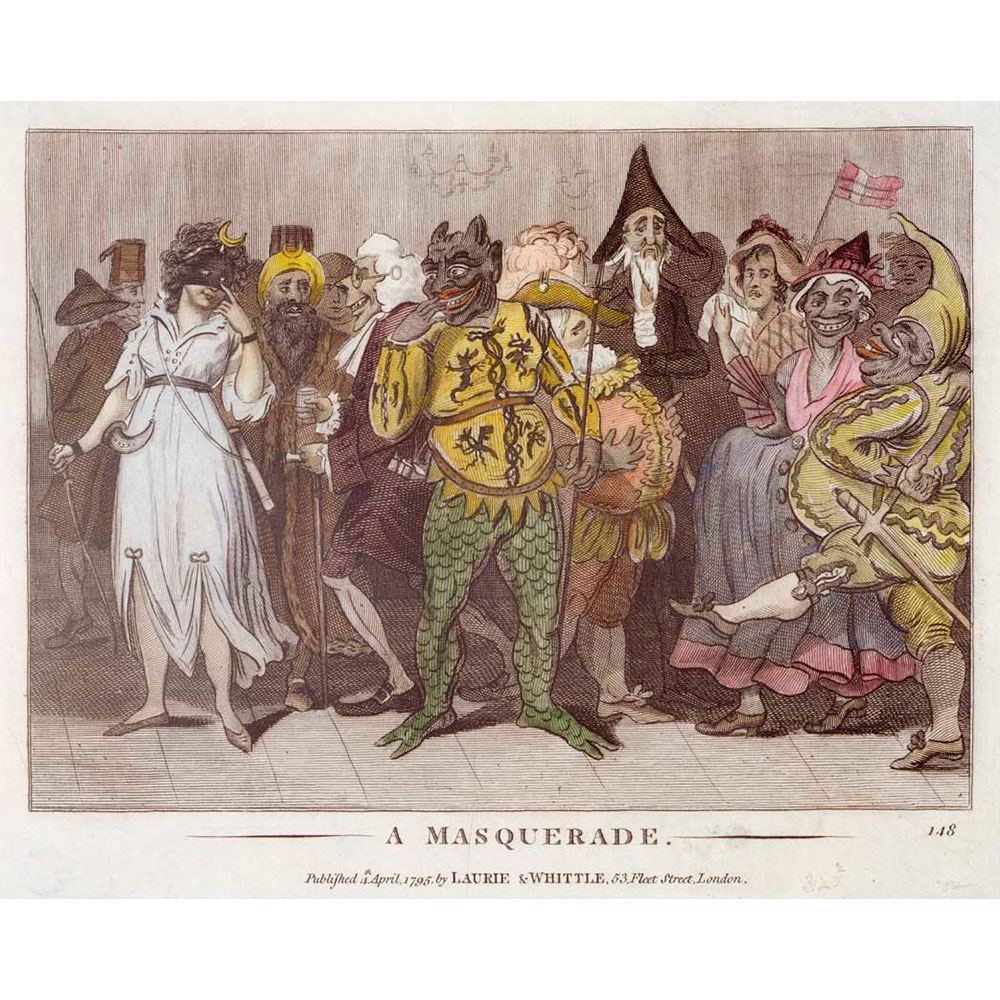

People from all walks of life enjoyed masquerading in the pleasure gardens of 18th century London assuming they could afford the expensive tickets, often as much as one guinea which was a week’s earnings for a skilled laborer. The lavish entertainments at Vauxhall Gardens and Ranelagh Gardens were inspired by the Venetian ridotto, private gambling salons where masked patrons remained incognito. In similar style, London’s rich, famous and infamous could congregate to flirt and intrigue in the guise of heroes and goddesses from antiquity and characters from the commedia dell’arte. However, the licentious behavior of the revelers was often condemned as immoral and scandalous and the popularity of masquerades waned with the increased public moralism of the early 19th century.

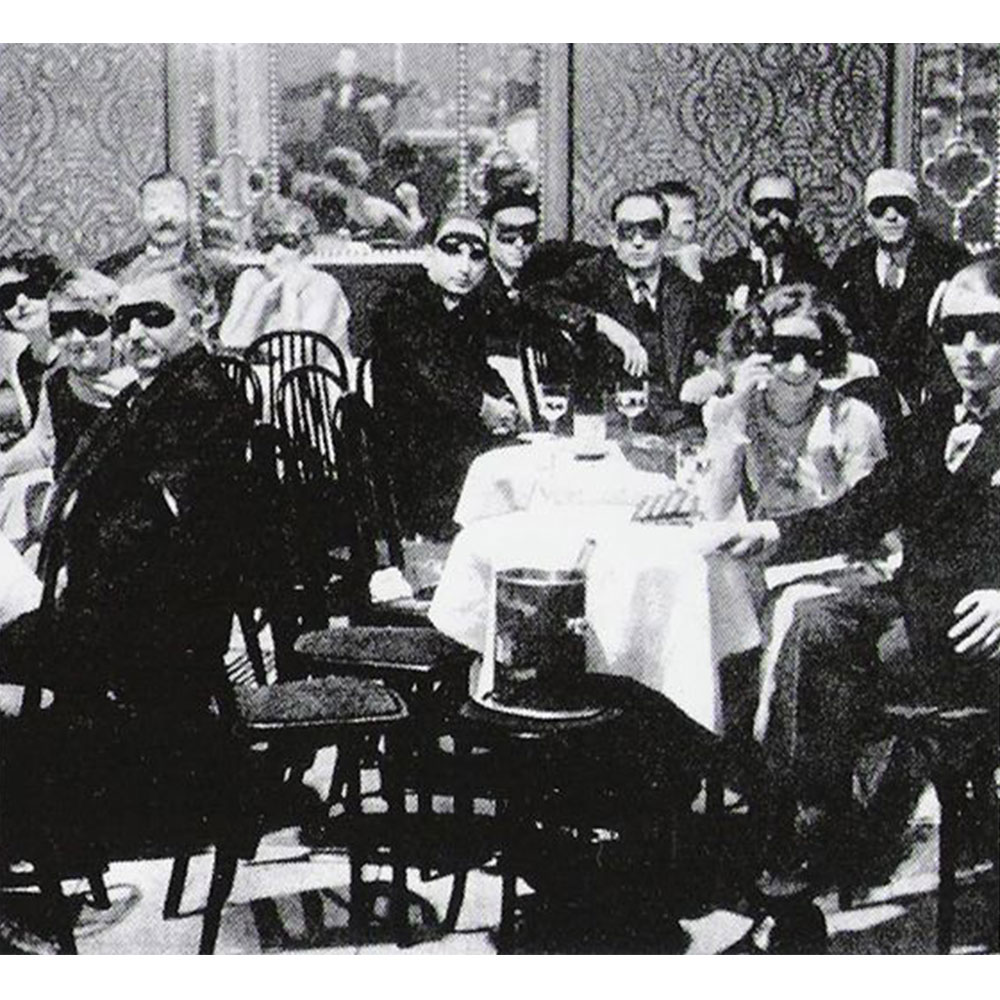

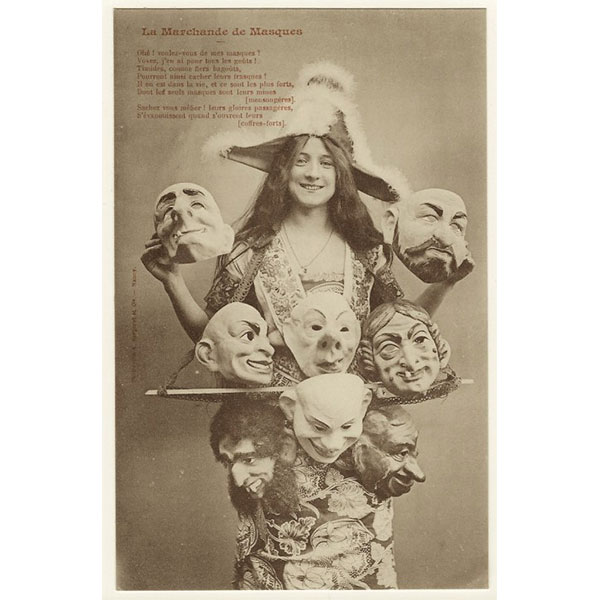

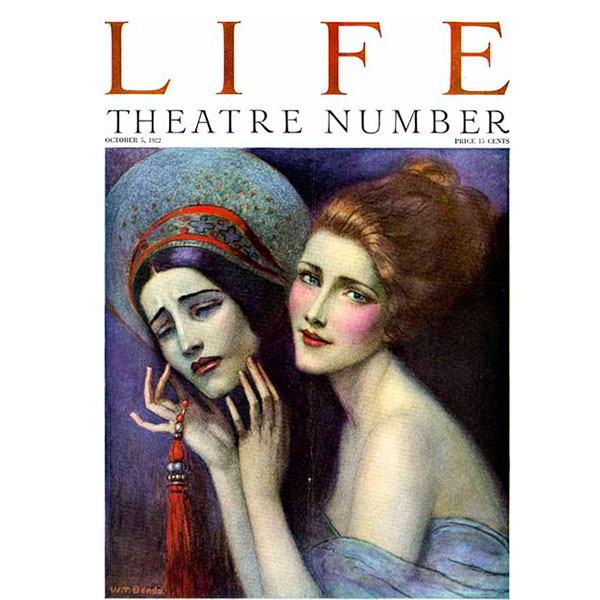

Masking became popular again at nightclubs and cabarets in fin-de-siecle Paris, such as the Folies Bergère. The French cabinet card depicts a female mask seller photographed by Albert Bergeret, who specialized in pin-ups of pretty girls in typically male professions. The cabarets of Weimar Berlin were also renowned for their decadence during the 1920s. One of the most famous, the Weisse Maus (the White Mouse) staged naked “beauty” dances and offered masks to customers who wished to obscure their identity. In America, the artist W.T. Benda became famous for his papier-mâché masks which were used in stage productions and masques in New York City.

Masqueraders of the Jazz Age often dressed up as Harlequin, Columbine and Pierrot as can be seen in the porcelain sculptures from Royal Doulton, Goldscheider and Hutschenreuther. Many other dramatic stage costumes were plagiarized by the mischievous flappers and vamps. Mephistopheles, a demon who corrupts men and collects the souls of the damned for Lucifer, evolved into Mephisto, the traditional demon king of pantomime and loaned his scarlet cloak and devil’s horns to devilish revelers.

Today the more sinister masks and costumes are associated with Halloween. All Hallows Eve on October 31 originated from the old Celtic festival of Samhain when it was believed that the ghosts of the dead returned to earth. Druids built huge sacred bonfires and made animal sacrifices to the Celtic deities. During the celebration, the Celts wore fearsome costumes, typically consisting of animal heads and skins and blackened their faces with ashes from the sacred bonfire to ward off the ghosts.

Join all the masked revelers at WMODA during our first Saturday opening of the season on October 27 and be first to see our new Fantastique exhibition. Watch Matteo Montagner from Balocoloc Artisans of Venice painting authentic Venetian masks and buy one for your next Halloween or Masquerade party. Meet glass artist and Chelsea Rousso and find out how you can make your own wearable glass mask as part of our Fantastique program.

Related Pages:

Masquerade Parties

Venetian Masks

Behind the Painted Mask

Sensational Saturdays

Royal Doulton Dante

Royal Doulton Aria

Pantalone, Columbine & Pulchinello

Plague Doctor Engraving

Perfume Seller P. Longhi

Venice Ridotto P. Longhi

Venetian Mask Shop

Commedia dell’arte Masks

Royal Doulton Queen Elizabeth

Royal Doulton Belle of the Ball

London Courtesan M. Laroon

Preparing for Masquerade

Masquerade Engraving

Royal Doulton Lady with Mask

London Pleasure Garden

Medieval Manuscript Animal Masks

Royal Doulton Bottom

Medieval Mummers

Royal Doulton Mask Seller

Pedlar of Masks W. H. Warren

Tudor Masque

Tudor Lady in Vizard

Tudor Vizard

Royal Doulton Harlequinade Masked

Royal Doulton Pierrette Masked

Weiss Mauss Cabaret

Royal Doulton The Mask

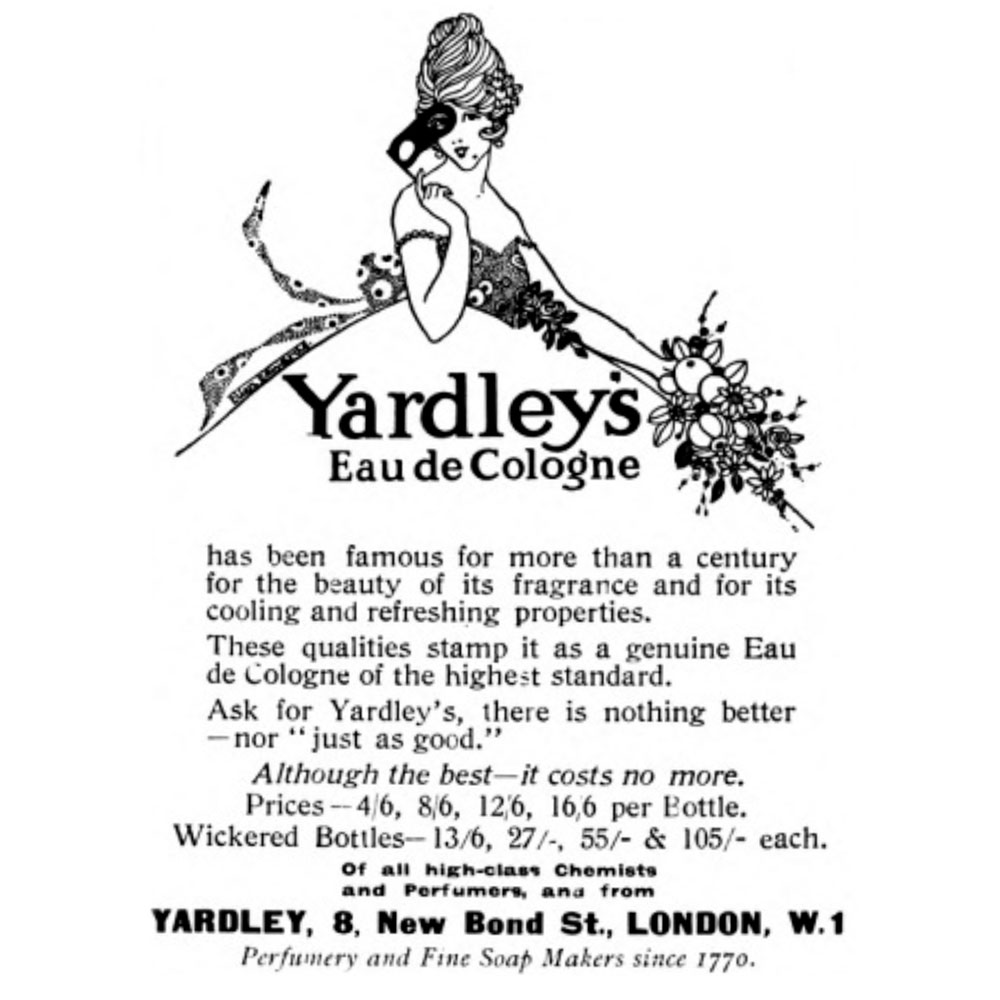

Yardley’s Advertisement

Pierrette Detail

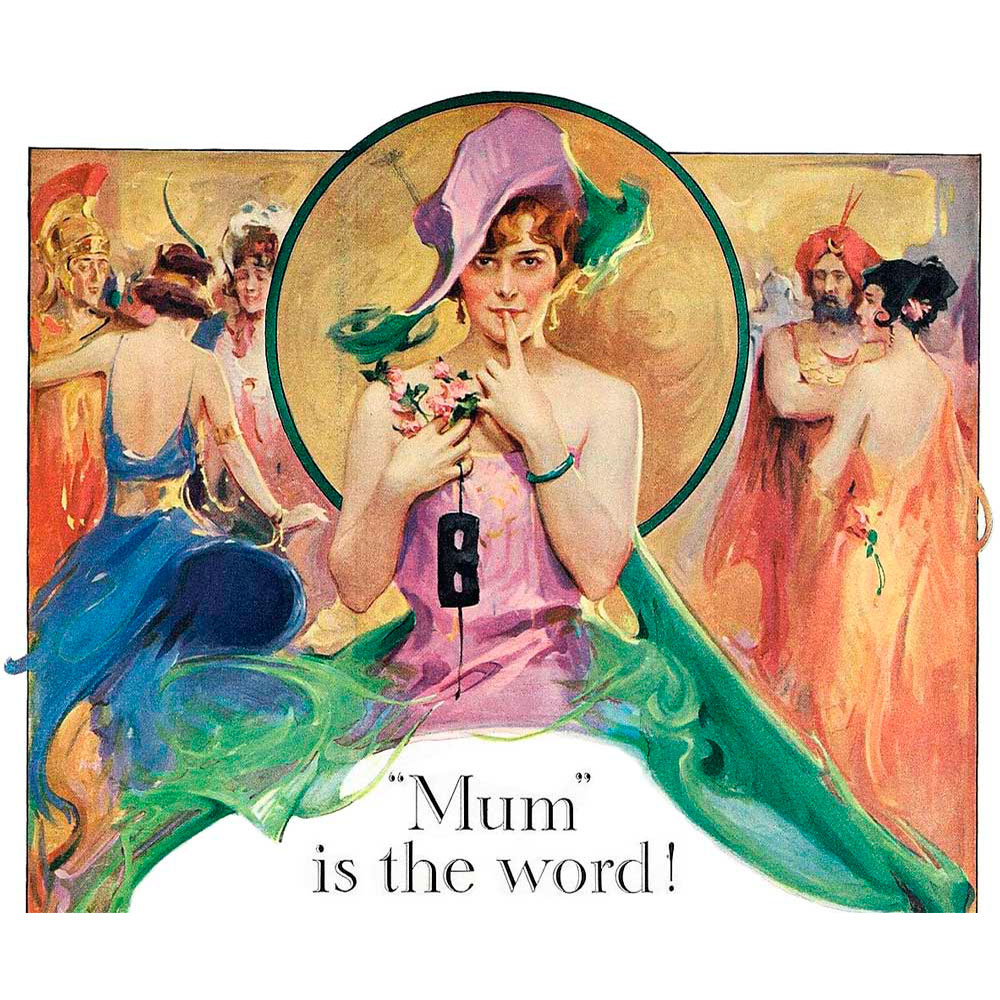

Mum Advertisement

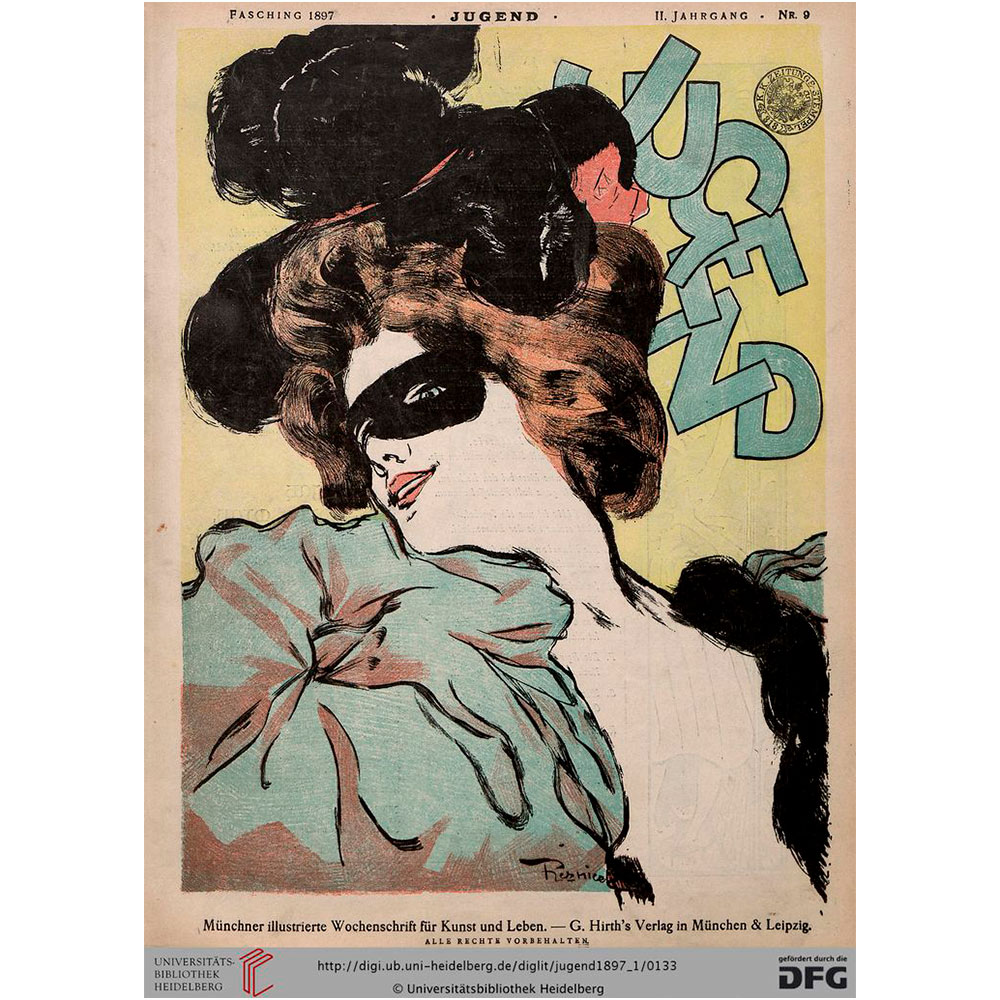

Jugend Magazine

Chelsea Rousso Glass Mask

Matteo Montagner Balocoloc

Balocoloc Mask

Balocoloc Mask

Balocoloc Masks

Balocoloc Masks

Benda Mask

La Marchande de Masques

Life Magazine Benda