By Louise Irvine

Color and form became the new aesthetic of British art pottery in the late 19th century. Exhibitions of Chinese ceramics introduced English potters to the brilliant monochrome glazes of the Qing dynasty. By trial and error, they aspired to recreate intense blood-red flambé glazes known as “sang-de-boeuf” and misty soufflé glaze effects in various colors.

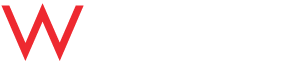

Ruskin Catalog with Souffle, Luster and Flambé Glazes 1905

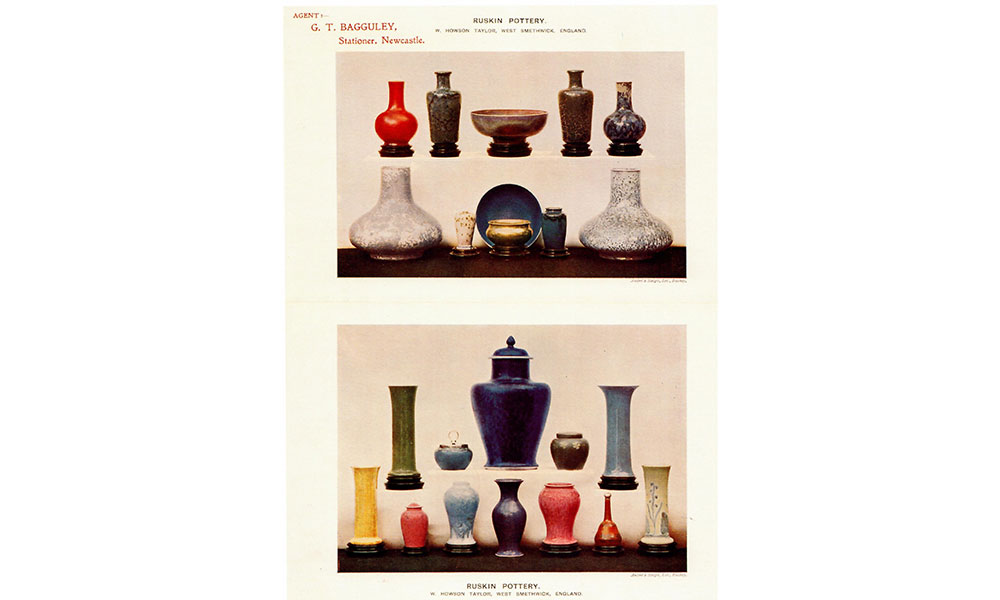

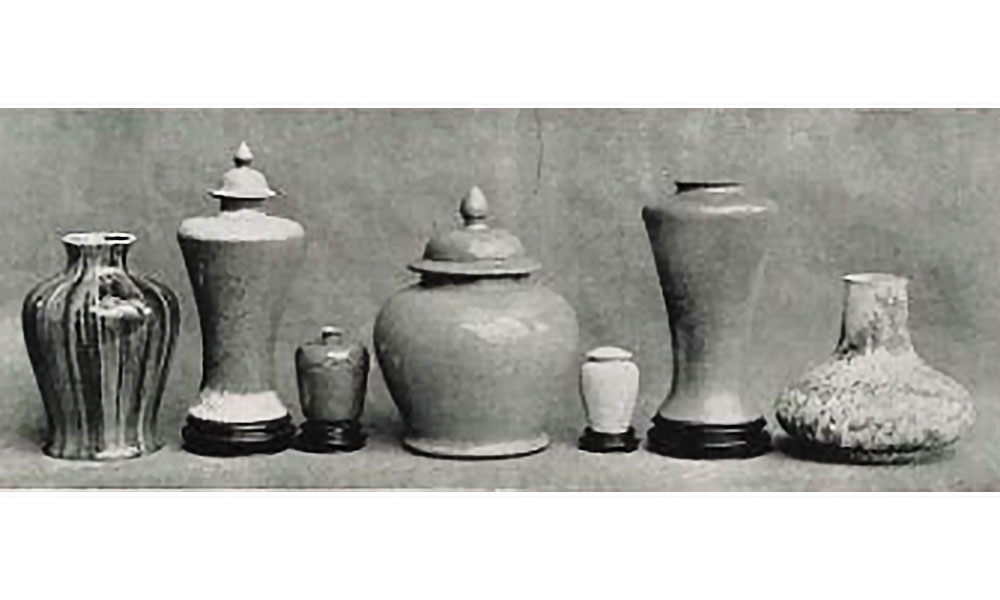

Ruskin Pottery St. Louis World's Fair 1904

Ruskin Pottery St. Louis World's Fair 1904

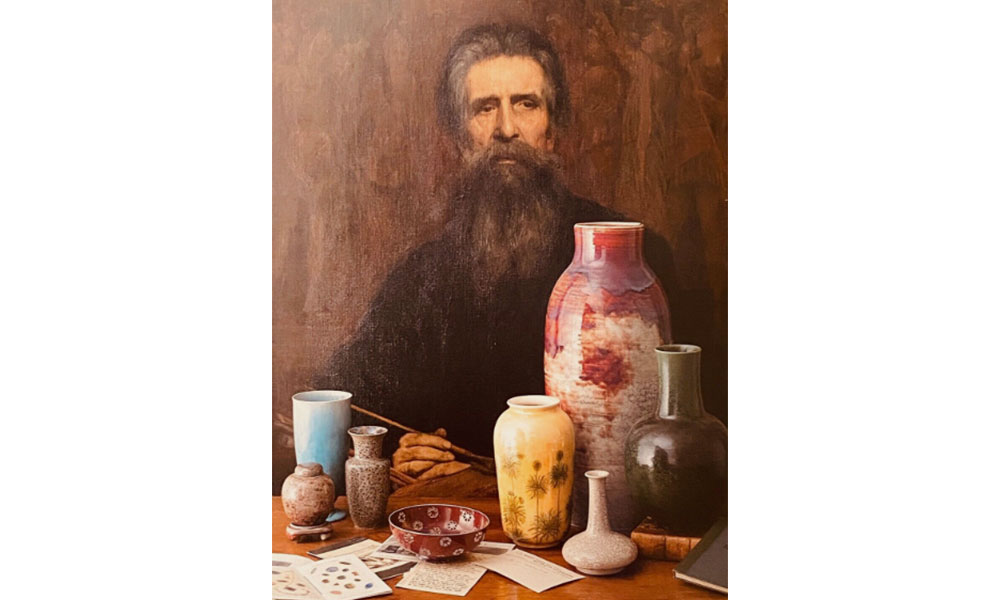

One of the most successful was Edward Richard Taylor, head of Birmingham School of Art, who established an art pottery in 1898 with his son, William Howson Taylor. Edward Taylor was born in Hanley in Staffordshire, the son of an earthenware manufacturer. As a boy, he worked for his father and studied at Burslem School of Art, where he decided to become an art teacher. After training in London, he taught at Lincoln and Birmingham art schools and established a considerable reputation as a painter of portraits and landscapes. He published several textbooks for students, revealing his long-held interest in ceramic design.

Edward Richard Taylor

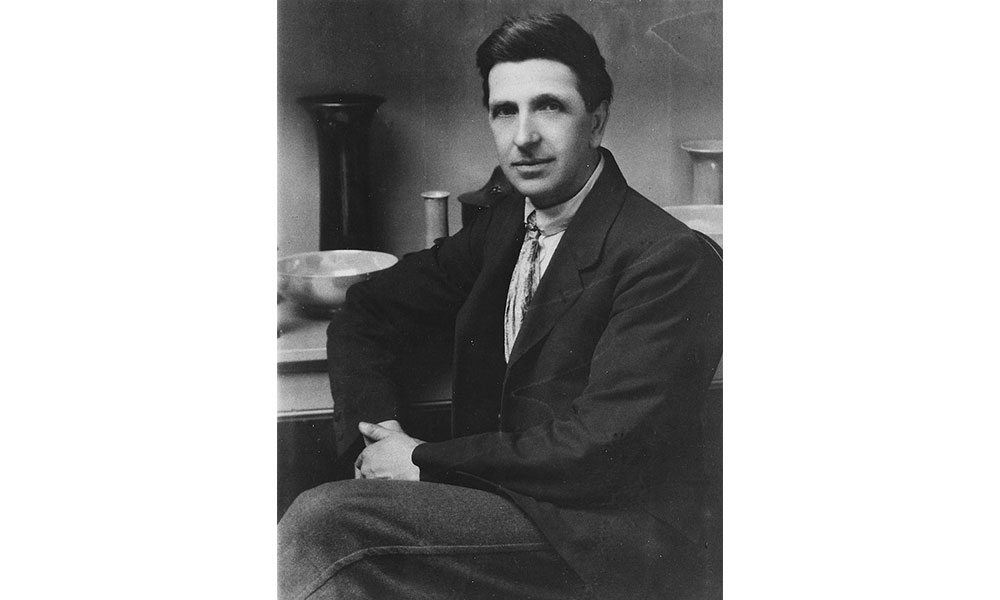

William Howson Taylor

Initially, Edward Taylor made pottery at home, an interest he shared with his son, who went to Stoke-on-Trent to learn practical pottery skills from his relatives in 1897. The following year, father and son set up a workshop to make tiles and art pottery in West Smethwick, where they built kilns and established supplies of coal, clay and glazes. Howson Taylor was fascinated with colored glazes, which he researched in his father’s extensive library and experimented with continuously in the first years of their enterprise. Undoubtedly, he was aware of the landmark exhibitions of Chinese ceramics held at the Burlington Fine Arts Club in 1895 and 1896. Howson later claimed it was three years before a single vase was allowed to leave the pottery due to his quest for excellence.

Ruskin Lemon Souffle 1901

Ruskin Lemon Souffle 1901

Ruskin Green Souffle c.1905

Ruskin Lavender Souffle 1911

Ruskin with Foliate Decoration 1905

Ruskin Pink Souffle 1914

Ruskin Orange Luster 1913

The shapes were designed by Edward Taylor and hand-thrown on the potter’s wheel “free from any mechanical process.” They were praised in the press for being “very thin, light and smooth to the touch.” Their early leadless glazes were admired for their harmonious “broken colors” and delicate hand-painted decoration, which contrasted with the “garish” productions of some factories. Their early soufflé glazes come from the French bleu soufflé, which describes the 18th-century Chinese technique of blowing cobalt blue in powder form onto the glaze. Rather than blowing, Howson Taylor sprayed cobalt to create his brilliant Lapis Lazuli effects, and he used the term “soufflé” to describe the glazes he perfected in various colors, including apple green and canary yellow.

Ruskin Flambé c. 1910

Ruskin Flambé c. 1910

Ruskin Robin’s Egg c. 1910

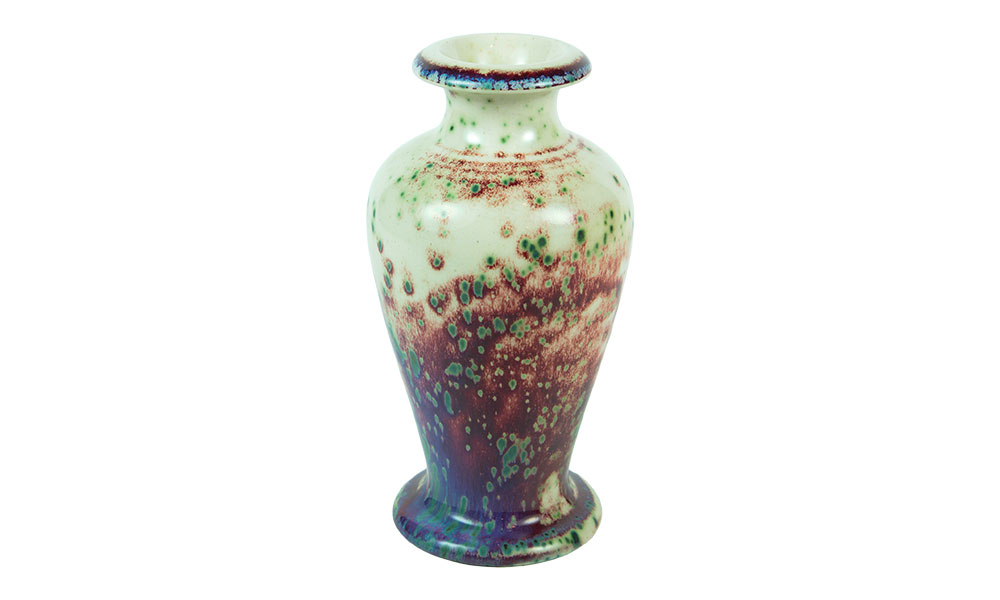

The most elusive and highly regarded color of the time was the Chinese-style sang-de-boeuf, and the Taylors were experimenting with these high-temperature transmutation flambé glazes in 1901. Their experiments in the “red” coal-fired kiln were always shrouded in secrecy, and the results were hard to predict. In addition to the intense rouge flambé glaze, the Taylors also achieved random splashes of green with their reduction-fired copper oxides, crushed strawberry and velvety peach blow glaze effects. One glaze was described as “dove-grey with pigeon’s blood diapering.”

Ruskin Flambé 1906

Ruskin Flambé c.1910

Ruskin Flambé 1905

Ruskin Flambé 1910

“Beauty of design, combined with beauty of color” was the expressed mission of the Taylors. They exhibited their work at Arts and Crafts exhibitions around the country and adopted the name Ruskin Pottery in honor of John Ruskin, the renowned Victorian artist and writer. As early as 1901, pieces were purchased by the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, followed a few years later by museums in Glasgow, Manchester and Liverpool. Silversmiths and electroplaters secured some of the pottery’s early production for mounting in metal. Small Ruskin Pottery roundels were set as gems in decorative woodwork and metalwork and sold at fashionable stores such as Liberty’s of London.

Ruskin Srawberry 1916

Ruskin Lavender 1921

Ruskin Rose Luster 1925

Ruskin Turquoise Souffle 1922

The Taylors entered the international marketplace at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904 and were awarded a Grand Prize. As a relative newcomer, receiving the highest award alongside industry giants such as Minton and Royal Doulton was an incredible achievement. According to the letter announcing their award, this major triumph was because of the admiration expressed by the Japanese experts for their colors and glazes, which “successfully reproduced some of the best glazes of the Ming dynasty.”

Ruskin Pottery Book

Among the Ruskin Pottery colors acclaimed by critics and journalists were a brilliant sealing wax red, dappled-sky gray and mottled rose-du-barry. Howson Taylor also experimented with iridescent luster glazes in orange, kingfisher blue and peacock green. In addition to decorative art pottery, various glazes were used on practical pieces such as candlesticks, inkstands, and potpourri vases. Buttons for ladies’ dresses, hat pins and jewelry also became an important part of the Taylors’ business.

Ruskin Flambé 1930

Ruskin Sang de Boeuf c.1920

Ruskin Flambé 1933

Ruskin Flambé 1933

Their exhibition successes continued unabated at home and abroad until the death of Edward Taylor in 1912 followed by the outbreak of the First World War, which dragged on until 1918. However, during the 1920s, Howson Taylor was working on some of his most spectacular high-fired glaze effects combining contrasting colors in matte and mottled hare’s fur and crystalline effects. No less than 1,500 experiments were carried out to achieve his innovative glazes. Shagreen was the name he gave to his ivory and green ground shaded with purple and flecked with dark green metallic spots. His robin’s egg glaze featured a pale green glaze shading to mauve and spotted with deep green. He exhibited these thickly potted tactile designs at successive British Industries Fairs and the 1925 Paris Exposition, which coined “Art Deco.” However, despite their brilliance, the demand for flambé and luster glazes was waning alongside the overtly modern designs of the era. Howson Taylor decided to close the Ruskin Pottery in 1933, but his retirement was short, and he died in 1935. True to his word, he destroyed all his glaze recipes as promised to his father. “I intend that my formulae and my secrets die with me…They will never be used for pottery again.”