by Louise Irvine

The Ardmore artists in KwaZulu Natal are known as the Isigwili, the fortunate ones. They enjoy a higher standard of living than their neighbors in this remote region of South Africa thanks to their work at the ceramic art studio. The Ardmore studio employs around 60 sculptors and painters and they work together in the spirit of Ubuntu, meaning “We are because of others.” Another popular African proverb “It takes a village to raise a child” highlights the importance of collective responsibility for children to grow in a safe and healthy environment. This ethos of community and traditional values can be appreciated at Ardmore particularly in the work of the artists who celebrate Zulu culture and lifestyles.

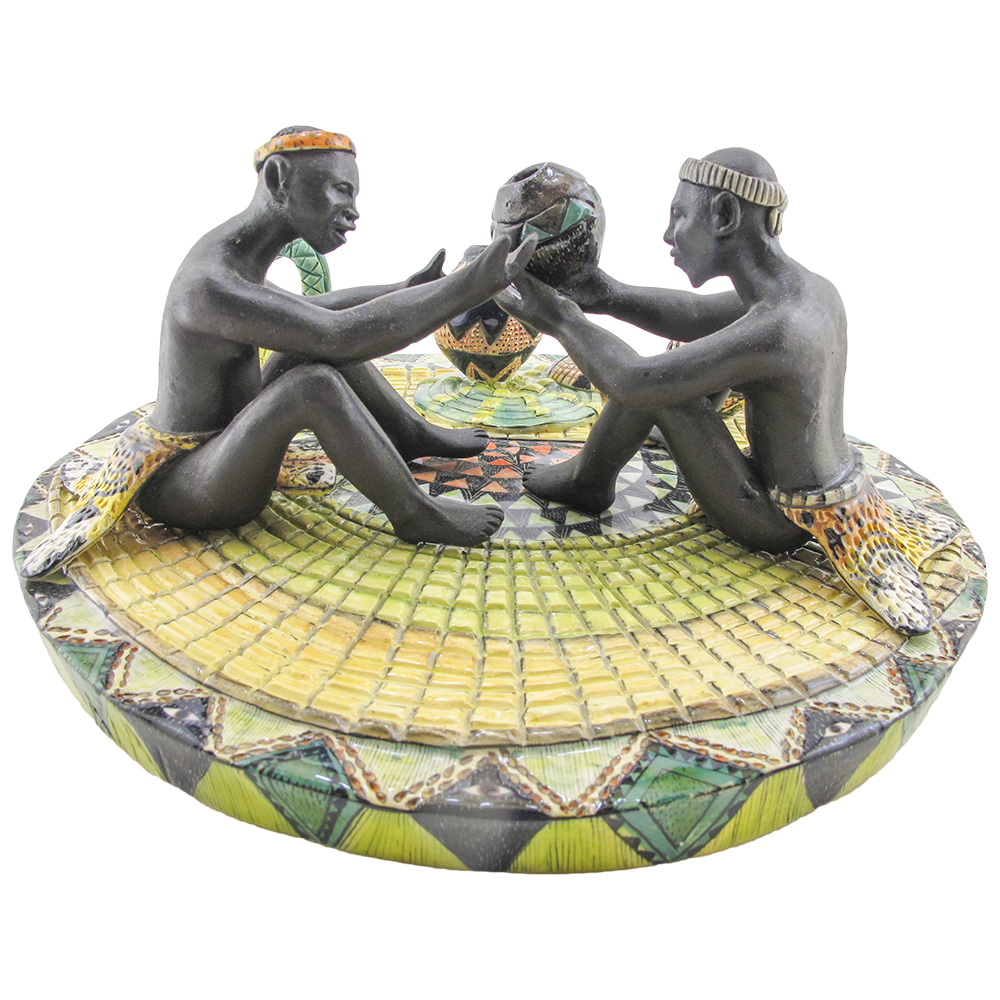

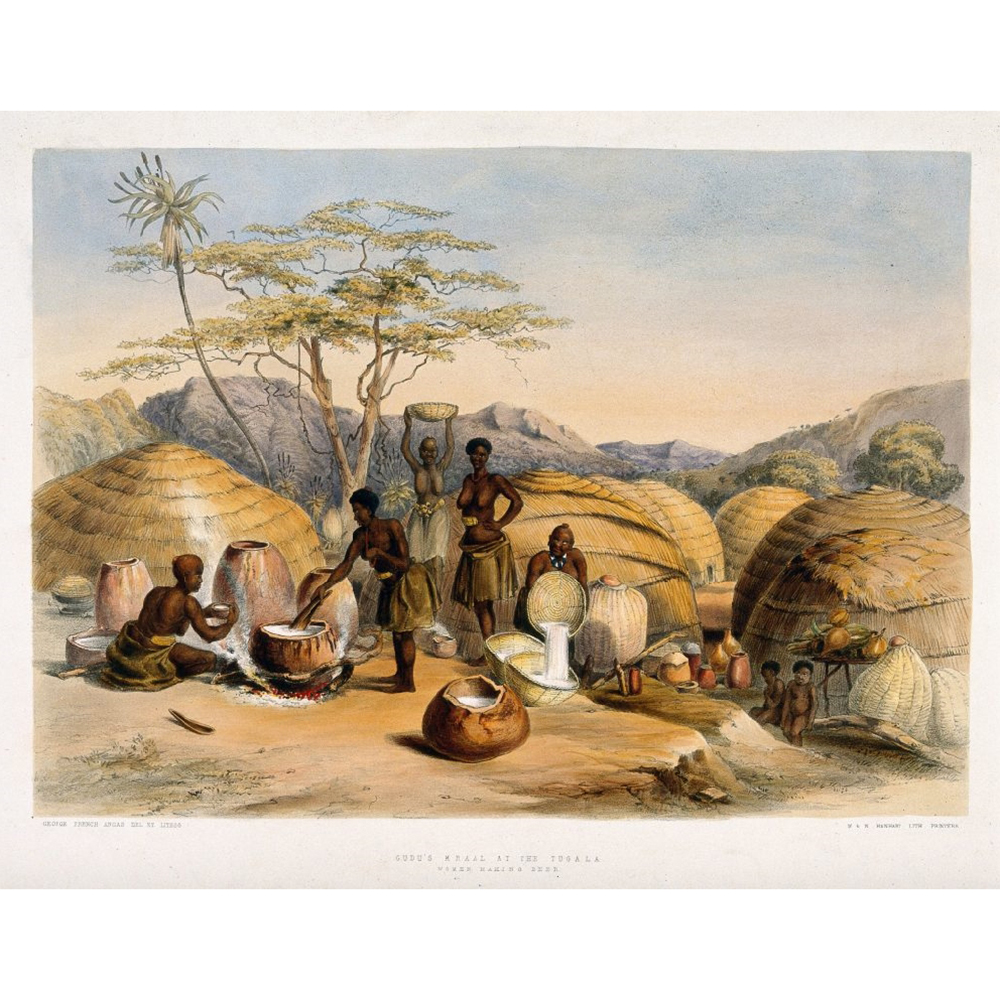

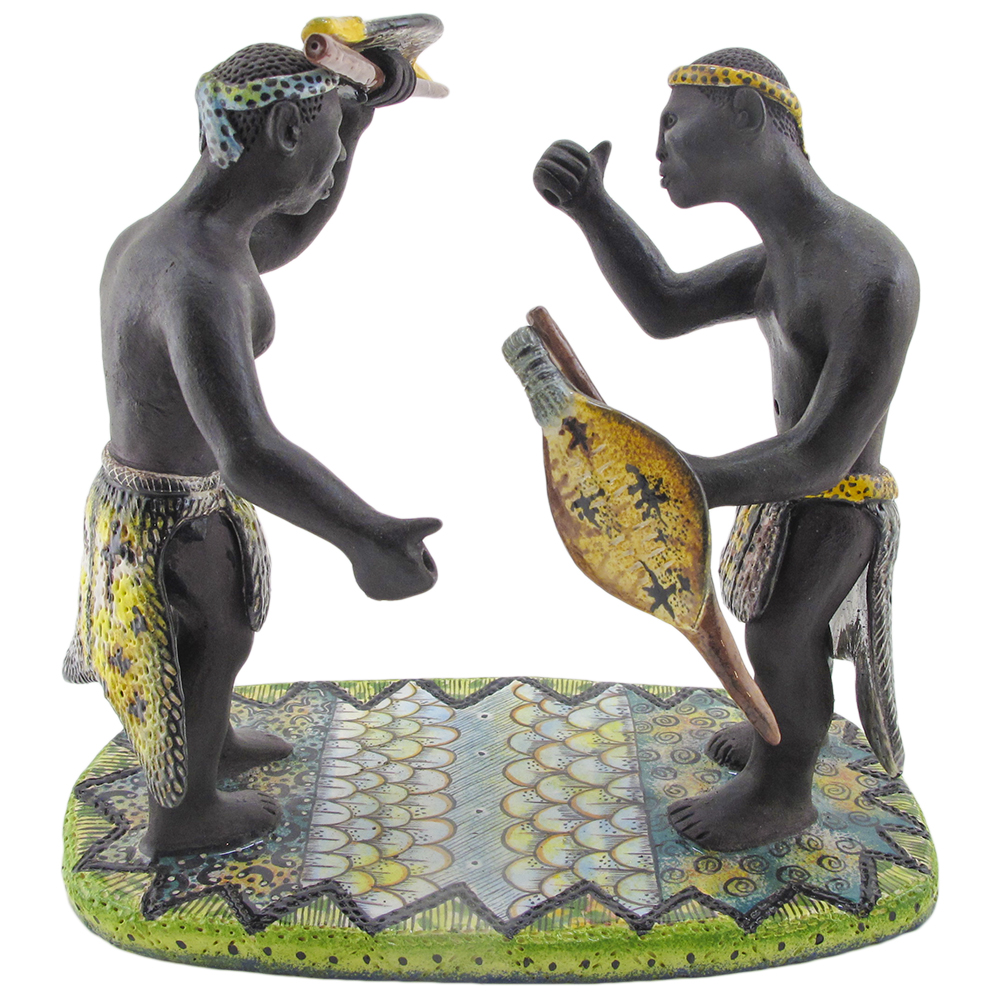

The historical Zulu village scene is by Nhlanhla Nsundwane whose life was anchored in his rural upbringing and pride in his people. The thatched hut is decorated with cow horns at the entrance signifying the importance of cattle to the Zulu kingdom. Women in traditional Zulu dress prepare a meal while the men discuss village business around a communal beer pot. One holds a shield made of cowhide and a knobkerrie, which was used for hunting and war.

Nhlanhla worked at Ardmore for 25 years and was one of the highly respected elders, who taught young recruits. His name means “good fortune” and it was his destiny to discover his extraordinary talent as a sculptor and earn a living at Ardmore despite many hardships in his young life. As a child, he contracted polio and his foot was later amputated. His wife Matrinah was an Ardmore painter who died tragically when their hut was hit by lightning. Nhlanhla was a very spiritual man and received a calling to train as a Sangoma but he returned to his home at Ardmore where he continued to sculpt figures of Zulu daily life until his death in 2015.

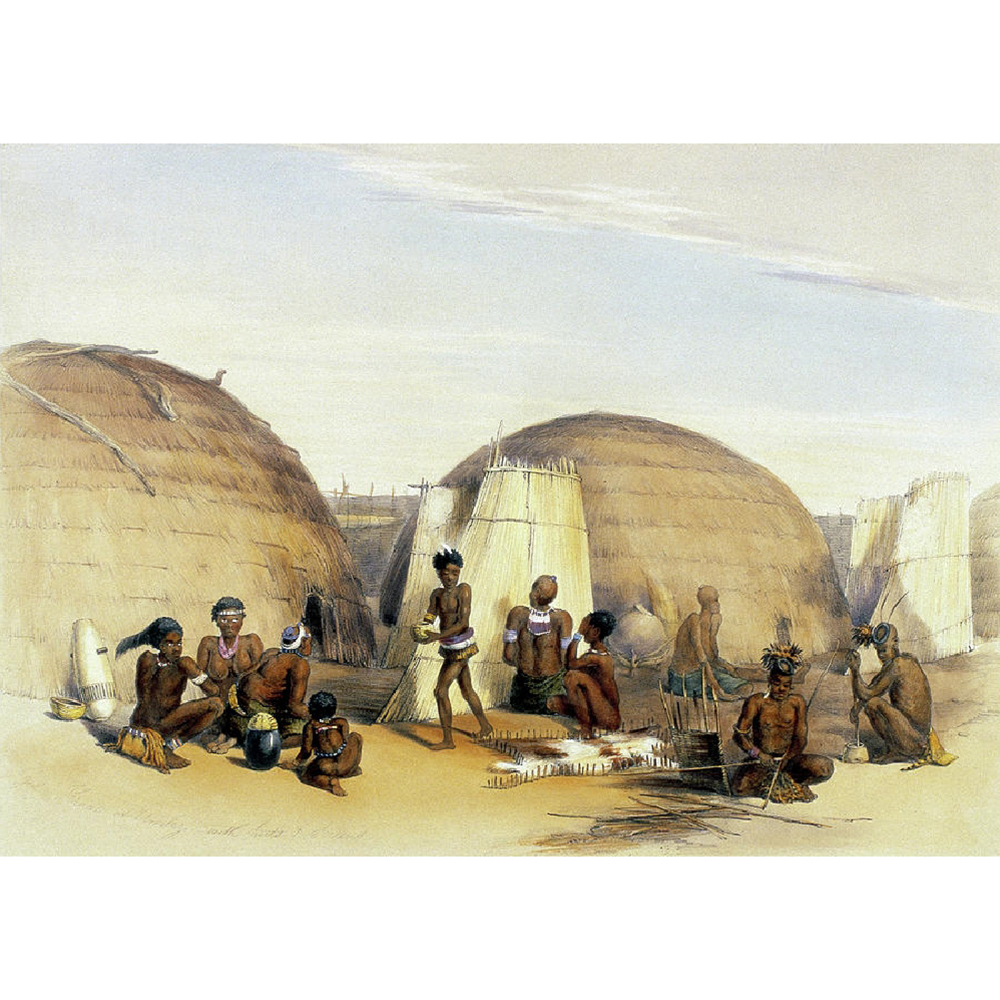

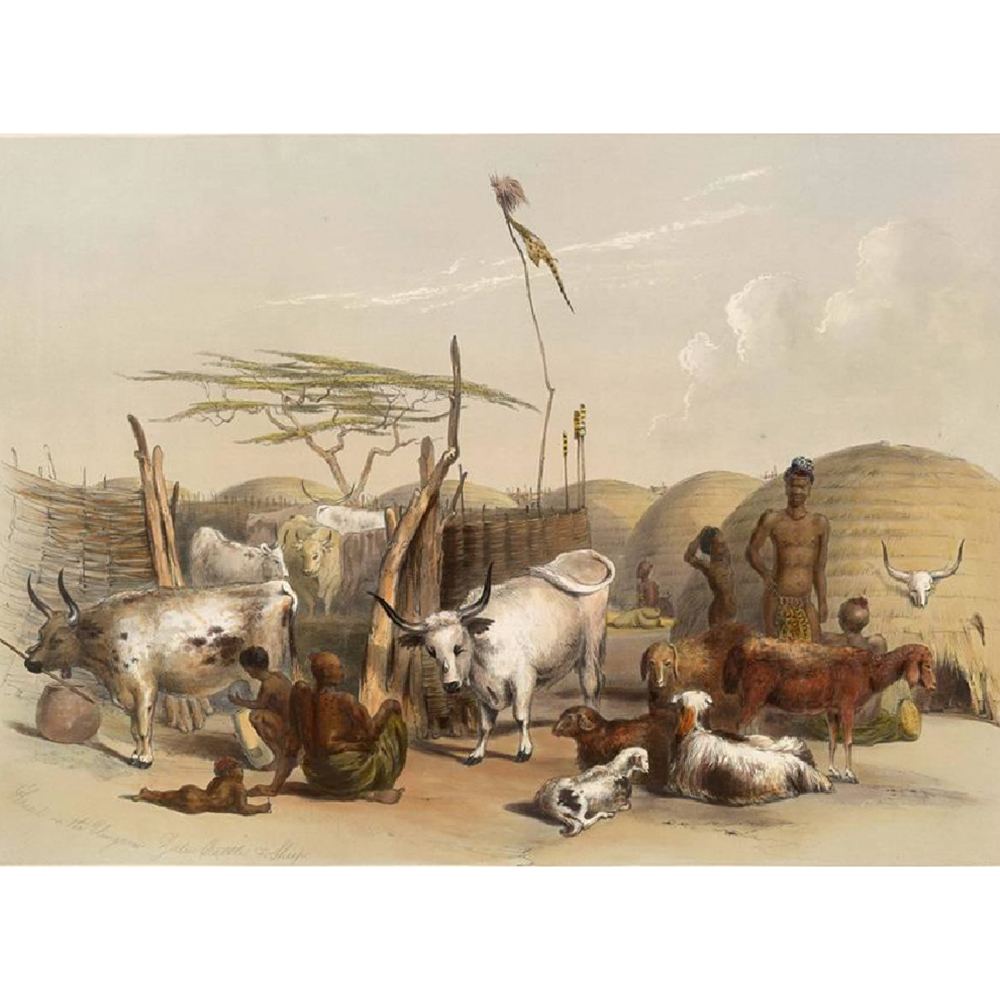

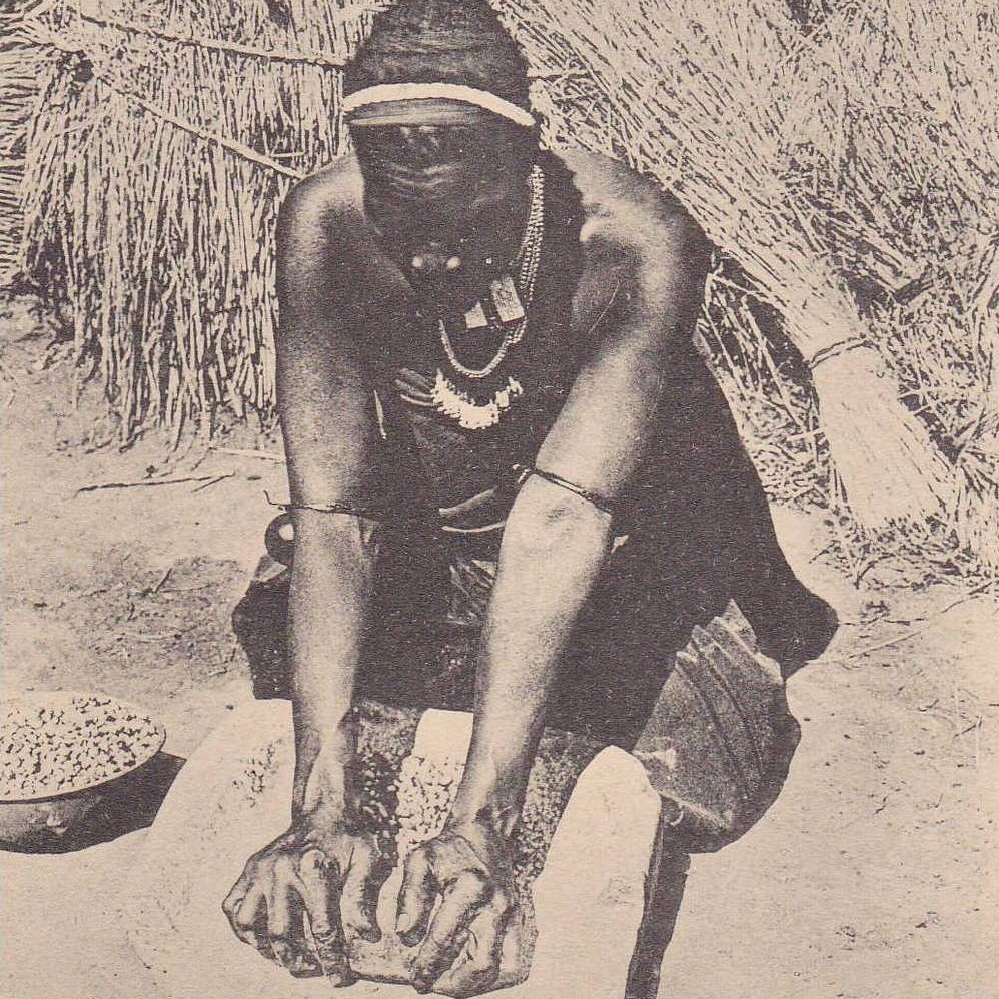

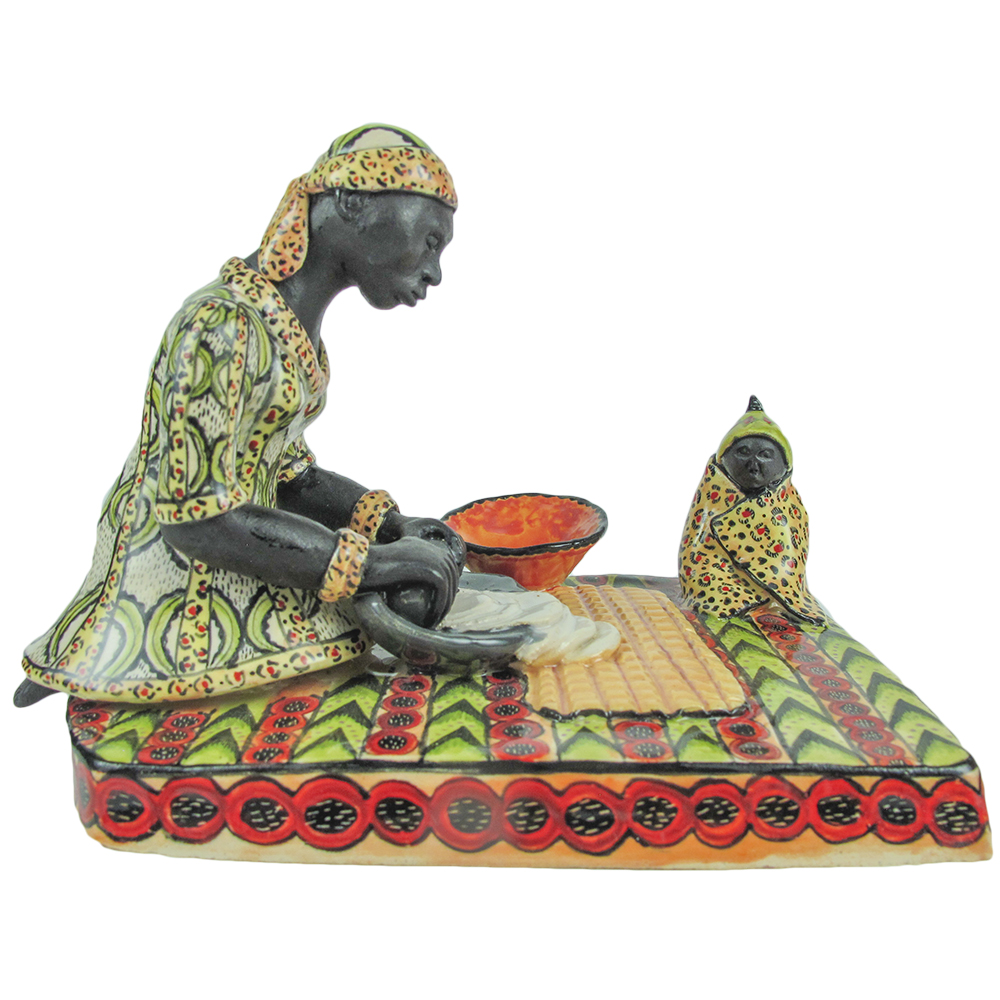

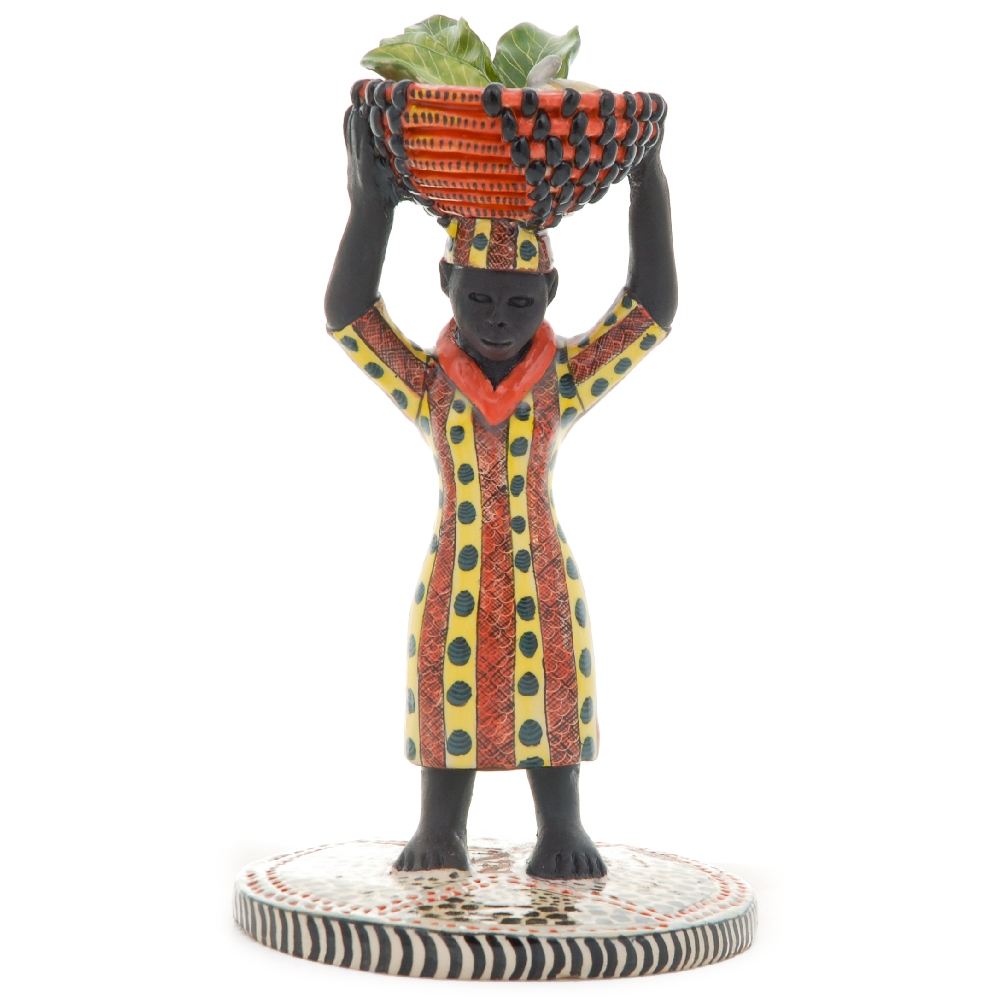

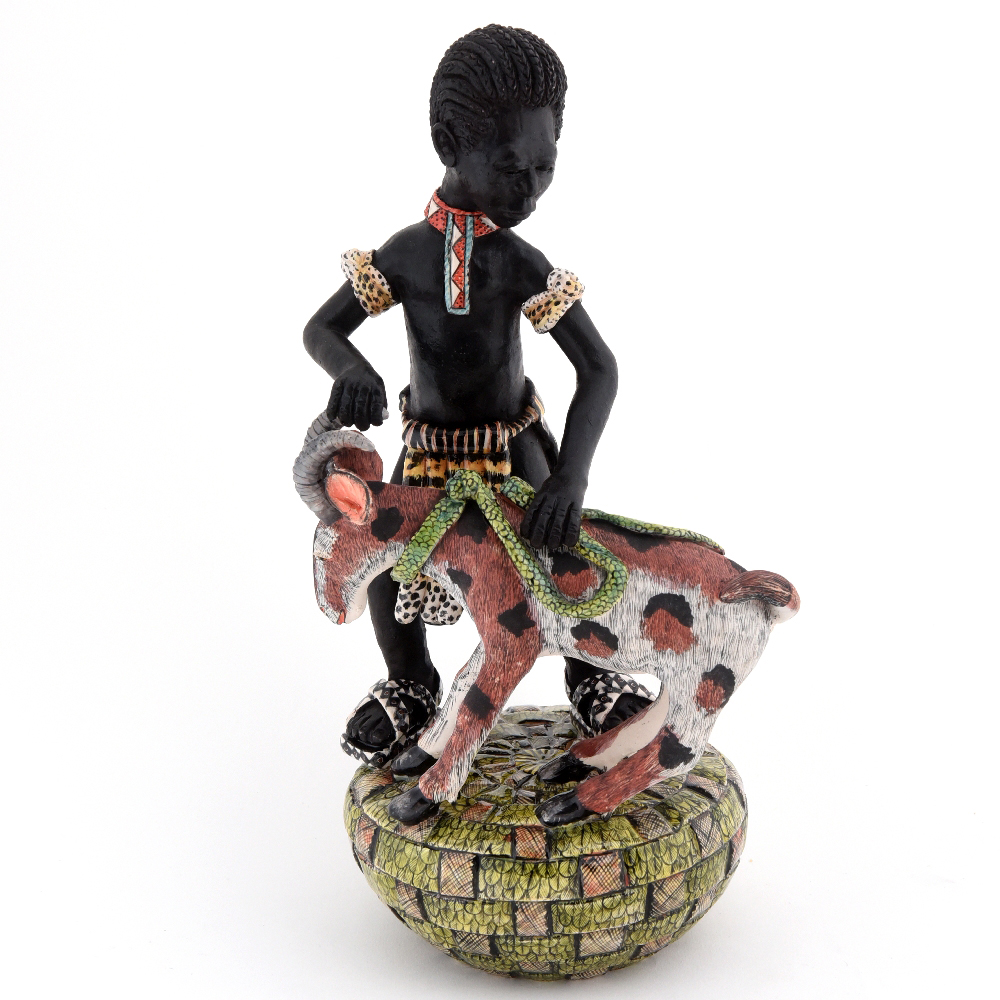

Nhanhla’s sculptures nostalgically portray village life of the past, including hunting, farming, and food preparation. Like many young Zulu boys in rural areas, Nhlanhla used to play with toy oxen that he fashioned from river clay. He was also inspired by Staffordshire figures shown to him by Fée Halsted, the founder of Ardmore. Historically, the Zulu economy depended upon cattle and agriculture and villages were economically self-sufficient. Growing vegetables and corn was the sphere of women, whereas cattle were tended by the men. A man’s wealth was counted in cattle. The Nguni breed provided meat and milk products plus hides for clothing and shields. Cattle also had enormous ritual value for honoring the ancestors, as well as the means of acquiring wives through lobola, or bride-price.

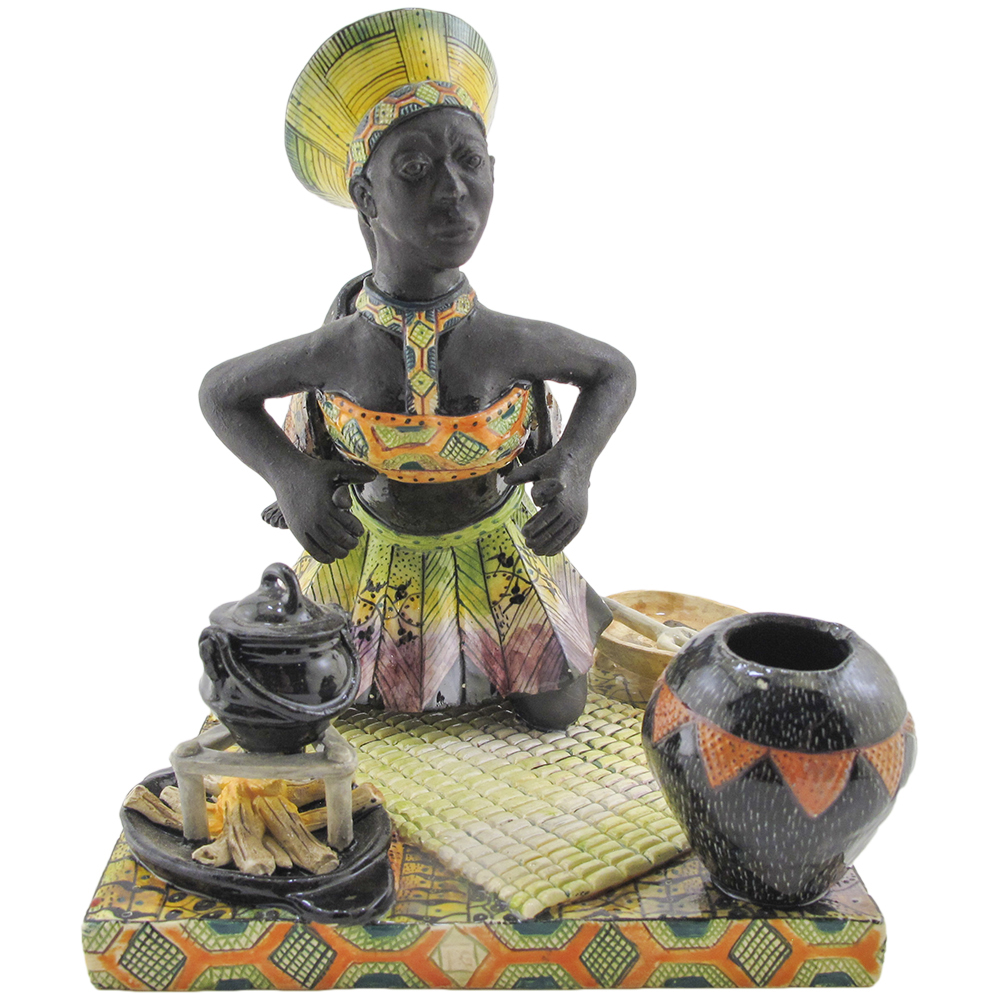

Young boys herded the cattle and milked the cows and men roasted the meat for ceremonies. Women prepared meals of vegetables and corn meal pap, known as mealie-meal. Beer was brewed by the women for hospitality and all types of ceremonies, including weddings and funerals. Legend states that Nomkhubulwane, the Zulu earth goddess, first taught them the technique for “tasteful hands.” Women also use clay from Mother Earth to create the pottery necessary for proper preparation and serving of this nutritious, grain-based drink.

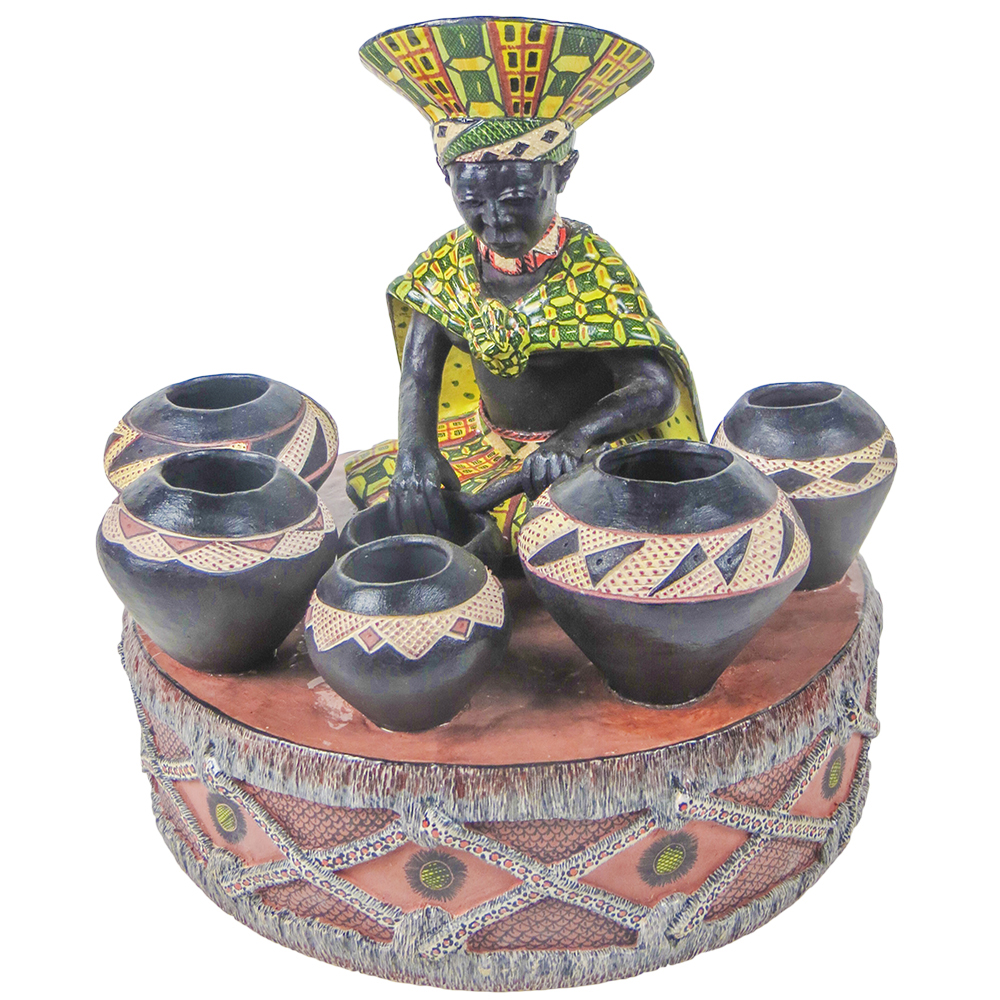

Several Ardmore figures depict Zulu women hand-coiling beer pots known as Ukhamba. The decorative raised bumps that appear in clusters are known as amasumpa and have been linked to cows’ teats, symbols of nourishment and wealth. Incised decoration is also common on the shoulder of the pots. Only black vessels are used at rituals and the distinctive finish is achieved by first burnishing them with a pebble and reducing oxidation during the open pit firing with wood and cattle dung. Soot, ash, and cattle fat are then added to the completed terracotta before firing again.

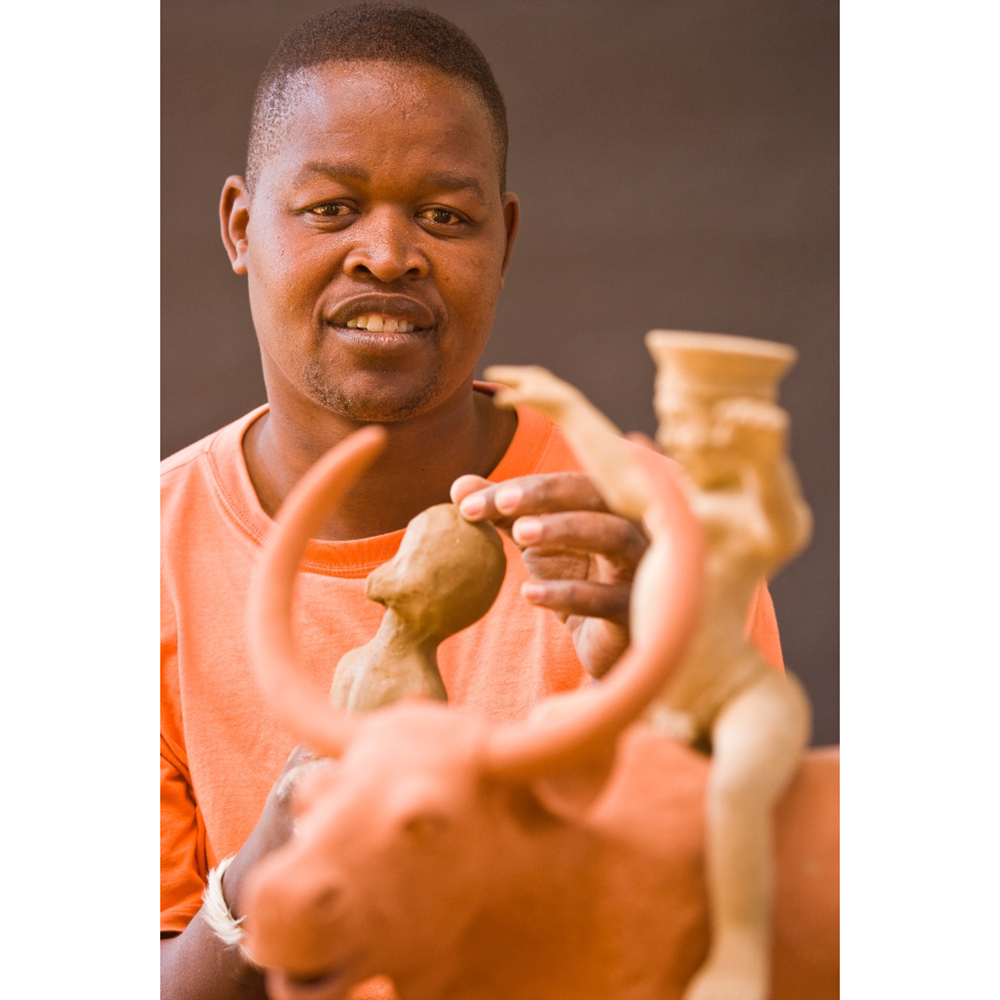

As well as portraying traditional Zulu pottery, the Ardmore artists have celebrated their own history. In 2014, in preparation for the 30th anniversary of the studio, they began sculpting a series of figures honoring their first artists, including Bonnie Ntshalintshali who was one of Ardmore’s early victims of AIDS. Many of these figures were modeled by Nhlanhla’s nephew, Petros Gumbi, whose superb sculpting ability has been recognized since 1999 when he joined Ardmore as a young man of 26. These unique tribute figures were intricately painted by the studio’s leading artists, including Jabu and Zinhle Nene and Roux Gwala.

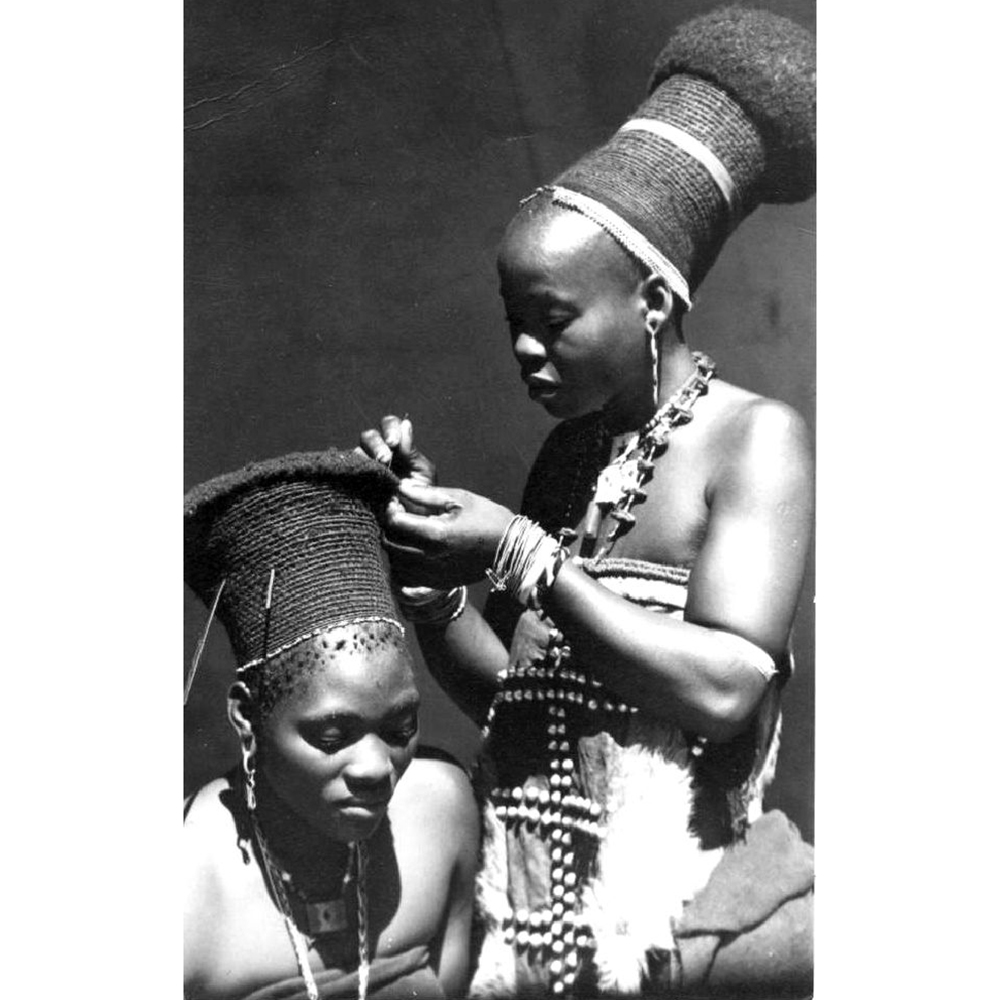

The family group modeled by Petros depicts authentic Zulu costumes worn by high status individuals. The women in the Ardmore figures wear vividly patterned fabrics. Their impressive hats are called Isicholos and they are traditionally worn by married women. They evolved from elaborate coiffures which were extended with woven grasses and false hair into conical shapes. Sometimes they are accessorized with beadwork for which the Zulu women are renowned. Today these hats are no longer daily wear, but they appear for festive occasions and are becoming a fashion statement among young South African women.

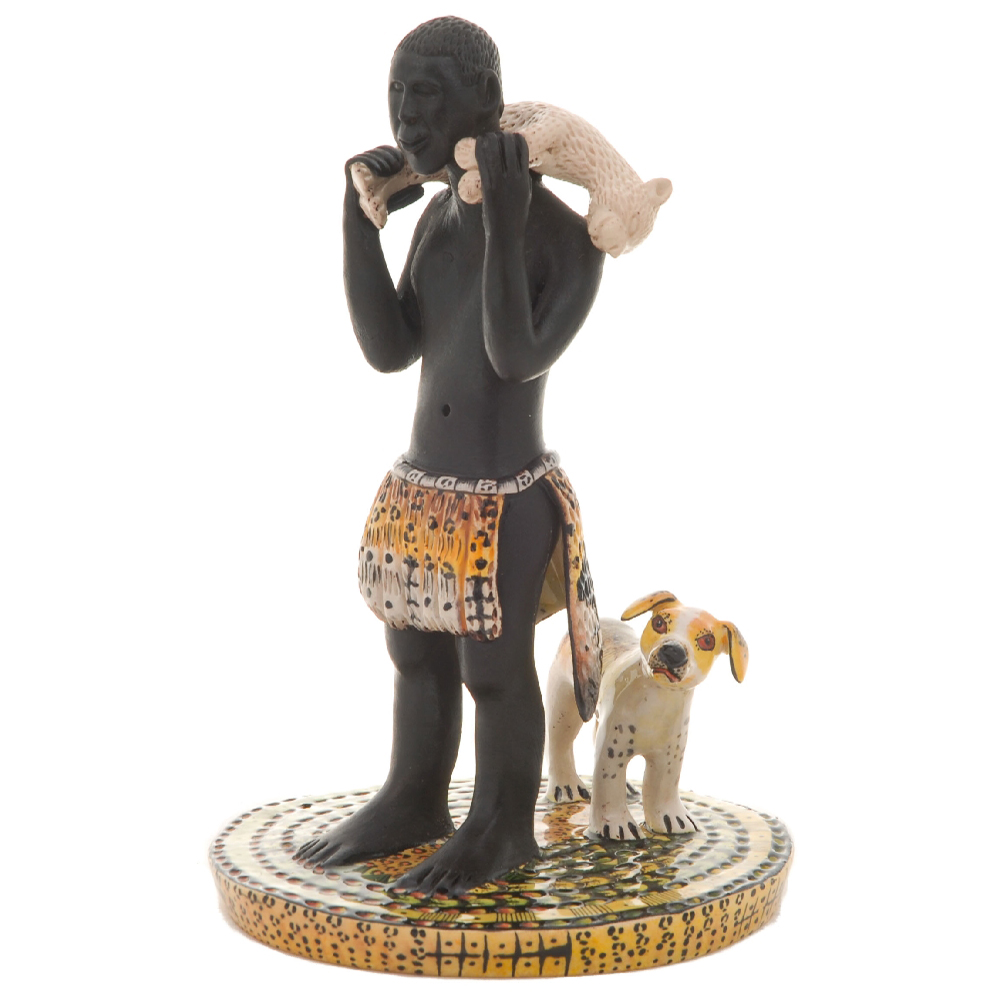

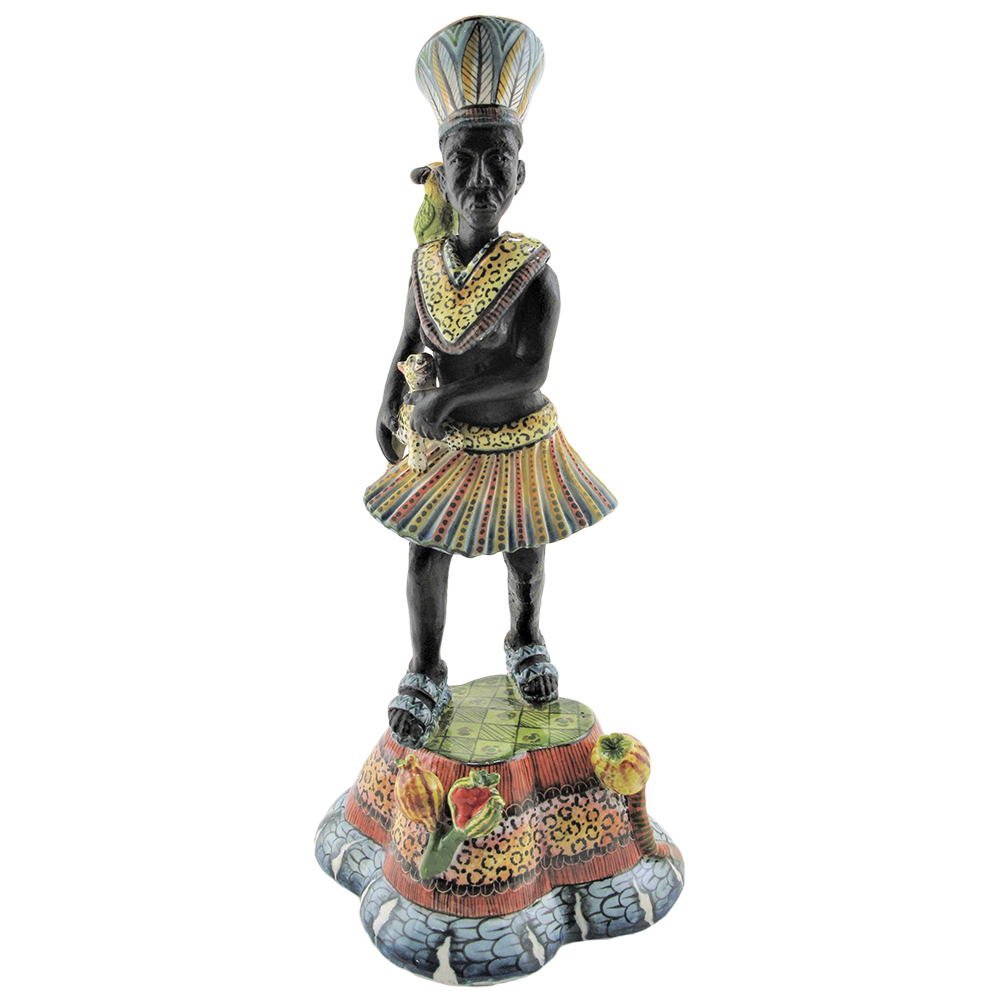

The Zulu men wear kilts with a front apron made of animal skins as well as leather bands around his arms and legs. Tails of civets and other wildcats sometimes adorn their costumes. Only men of an elevated social position wear leopard skin as it is revered as the king of predators. The distinctive Zulu sandals called Ezimbadadas are made of recycled car tires. The soles are cut from the tread and the uppers from the side. They are named for the sound they make when the hit the ground and can be seen in many of the Ardmore figures.

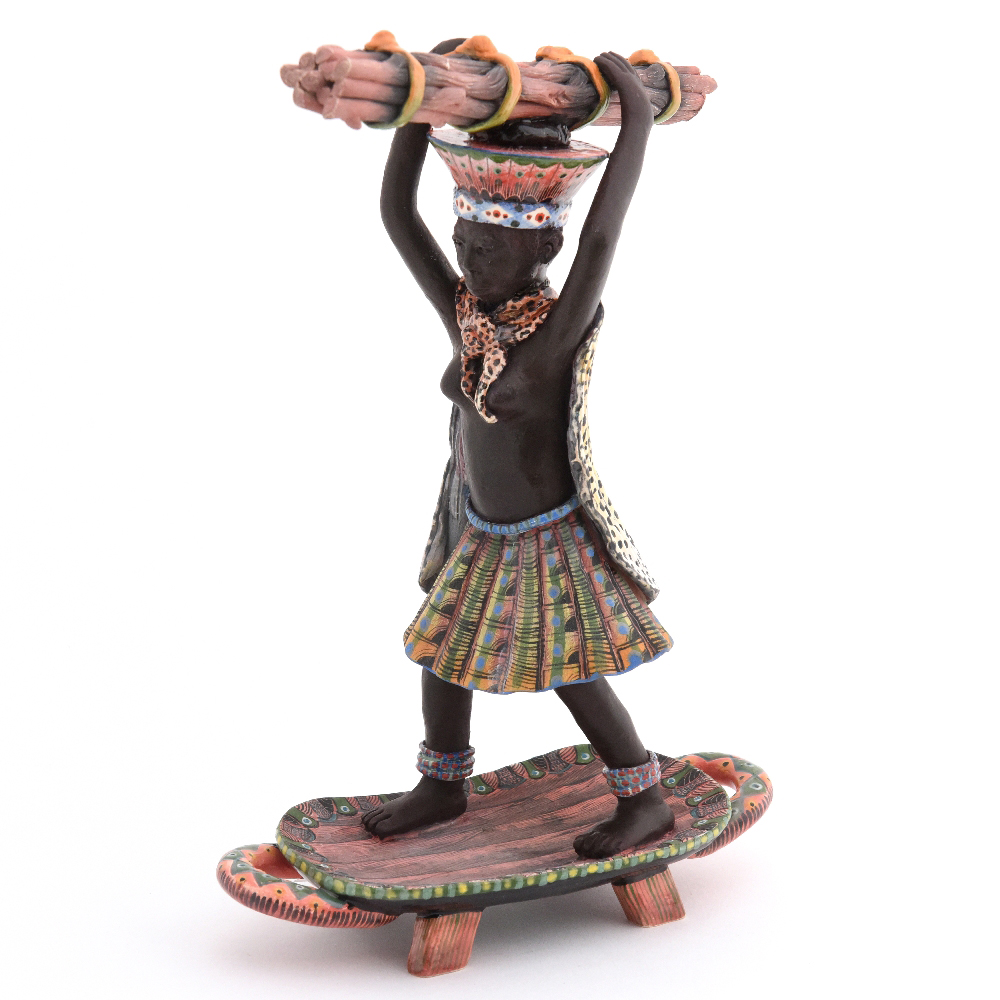

Some of the larger Zulu figures by Petros have unusual bases. The woman gathering firewood stands on a wooden meat platter known as a Ugquoko while the Zulu hunter stands on a three-legged cast iron cooking pot, which will be used to make potjiekos (pot food) from his prey. Another splendid Zulu figure by Qiniso Mungwe is harvesting pomegranates, which are symbols of abundance and fertility in many cultures. On his arm is a white Cockatoo which gazes greedily at the luscious fruit. Parrots feature in several of the Zulu figures, indicating their popularity as talking companions, but also highlighting their endangered status in Africa today because of the illegal pet trade.

The WMODA collection is particularly rich in Zulu cultural figures as the subject particularly appeals to Arthur Wiener. He has been collecting Ardmore since 2010 and is motivated by his appreciation of the artists’ work and the knowledge that his purchases help uplift their families in a region where poverty and unemployment are rife. Typically, the endeavors of each Ardmore artist support a large extended family of several generations. Elderly parents and grandparents are cared for and their children are being educated, with several choosing to pursue a career at Ardmore alongside their family.

Read more in the Ardmore book available from the WMODA museum shop.

Ardmore Village Scene by Nhlanhla and Roux

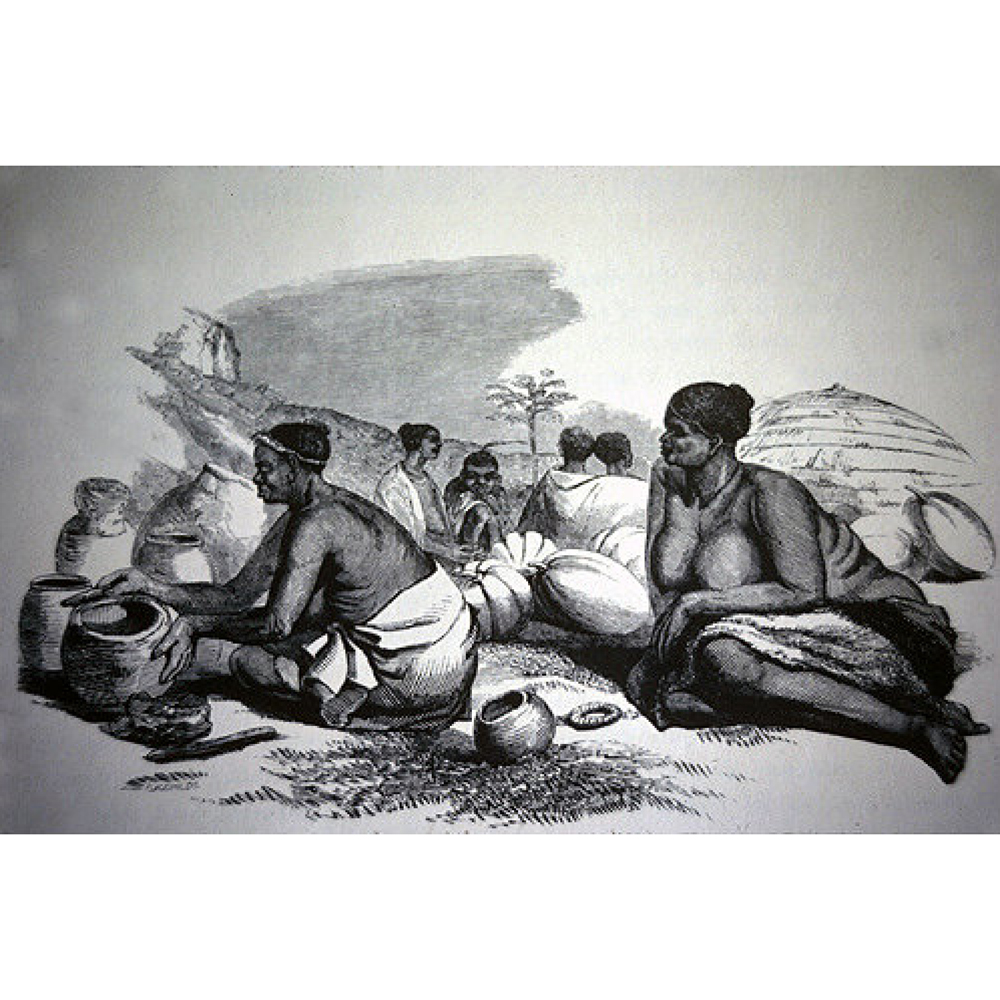

Zulu Kraal G. F. Angas

Sculptor Nhlanhla Nsudwane

Ardmore Returning from the Hunt by Nhlanhla and Roux

Ardmore Drinking Beer by Nhlanhla and Roux

Ardmore Milking a Nguni Cow by Sbusiso and Roux

Ardmore Plowing by Nhlanhla and Roux

Zulu Homestead with Nguni Cattle

Ardmore Tending a Goat by Nhlanhla and Sthabiso

Boy herding cattle

Ardmore Preparing a Meal by Sbusiso and Nondumiso

Grinding mealies

Ardmore Preparing a Meal by Nhlanhla and Xollie

Ardmore Harvesting Vegetables by Nhlanhla and Zinhle

Women Brewing Beer

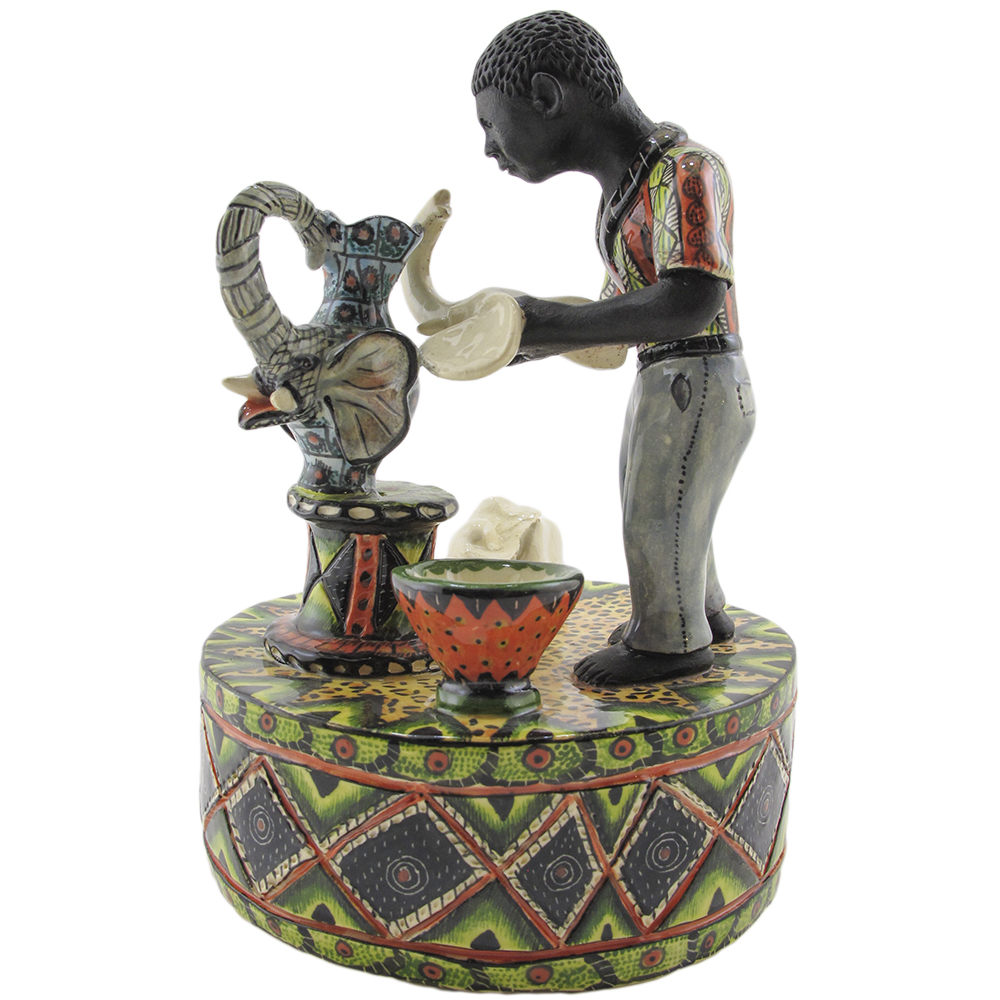

Ardmore Making Pots by Nhlanhla and Roux

Ardmore Painting Pots by Nhlanhla and Nondumiso

Ardmore Artist by Bennet and Jabu

Ardmore Artist by Petros and Jabu

Ardmore Sculptor by Nhlanhla and Xaba

Ardmore Zulu Clay Figure by Petros

Ardmore Mother with Baby by Petros and Roux

Ardmore Artist by Bennet and Mthulisi

Ardmore Potter by Petros and Jabu

Zulu Potters

Women carrying beer pots

Zulu vessel with amasumpa

Beer Pot Detail

Ardmore Remember Bonnie by Petros

Ardmore Zulu Royal Family by Petros and Mandla

Ardmore Woman with Monkeys by Petros and Punch

Ardmore Zulu Woman by Qiniso and Mama

Zulu hat

Zulu women

Sculptor Petros Gumbi

Ardmore Man with Dog by Petros and Siyabonga

Ardmore Man with Goat by Petros and Zinhle

Ezimbadada

Ardmore Man with Birds by Qiniso and Elvis

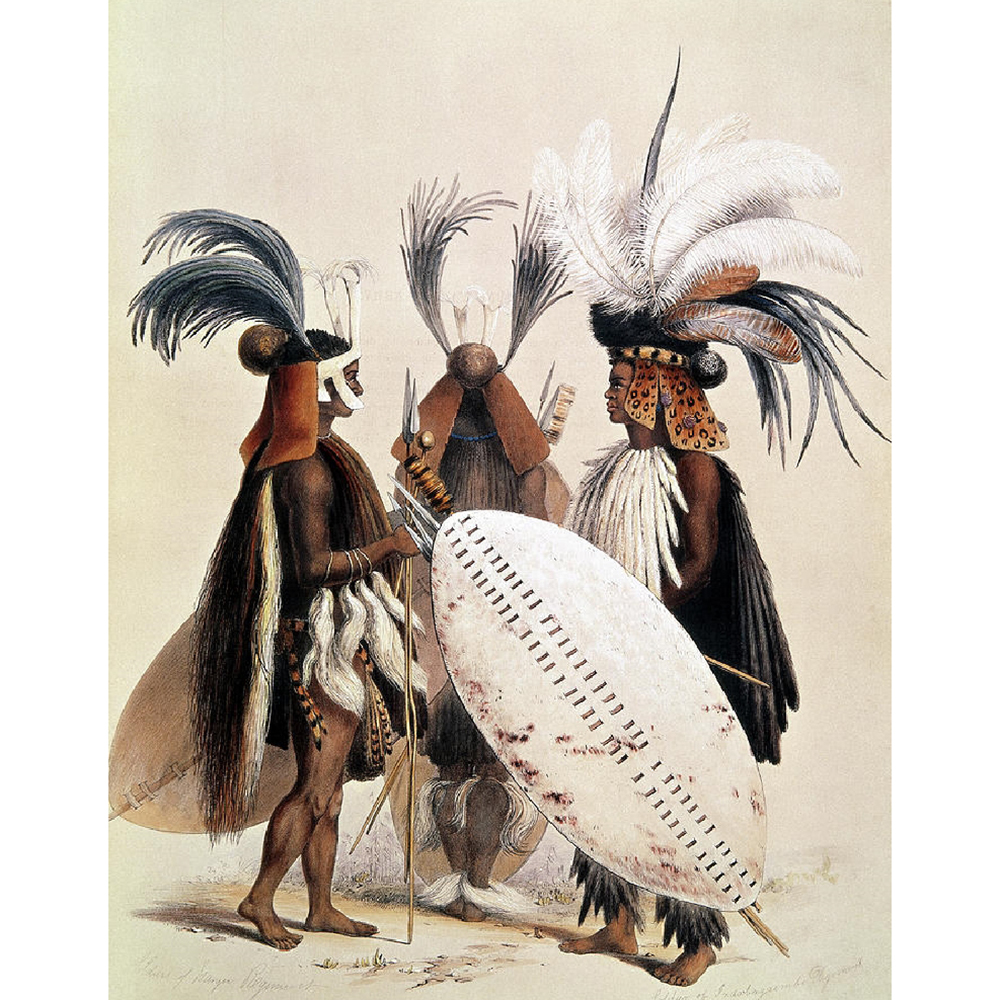

Zulu warriors

Ardmore Zulu Warriors by Qiniso and Elvis

Ardmore Woman Carrying Firewood by Petros and Siyabonga

Wooden meat tray

Ardmore Book