Imagine a time when many people believed that fairies really existed. When Tinker Bell was dying in J.M. Barrie’s 1904 play Peter Pan, everybody in the audience had to save her by crying out, ‘I do believe in fairies!’

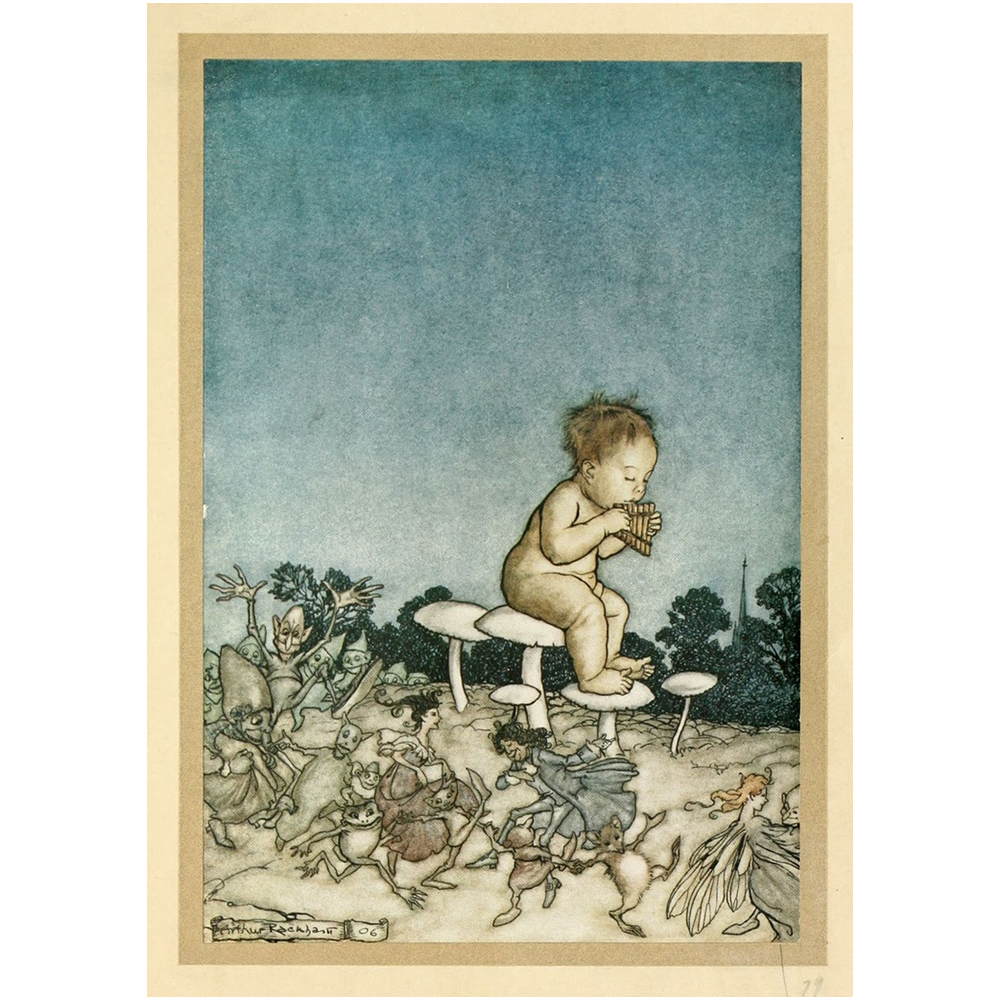

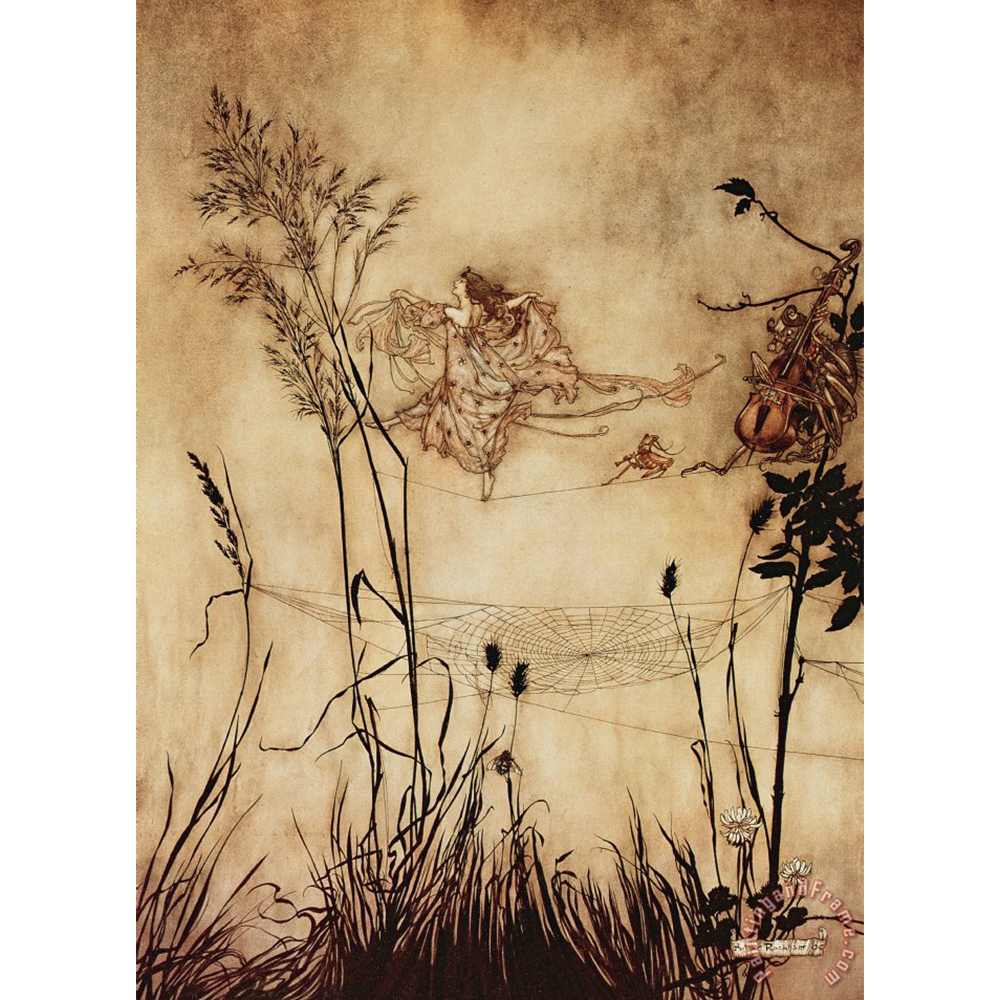

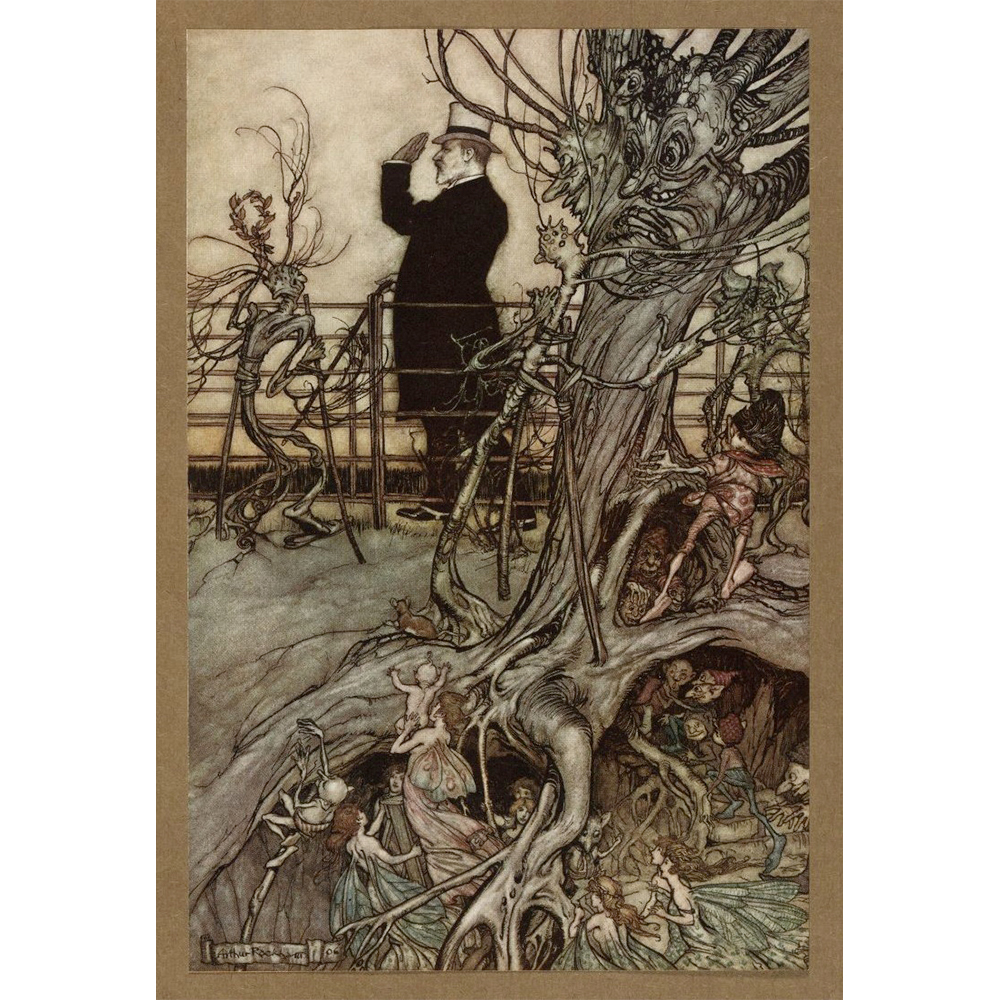

In his book Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, J.M. Barrie claimed that fairies came out to play when the London park closed at night. These were not all dancing fairies with diaphanous dresses, as can be seen in Arthur Rackham’s illustrations for Barrie’s book, which feature sprites, gnomes and other mischievous fairy folk. Rackham’s supernatural residents of Kensington Gardens inspired Charles Noke to create the striking Gnomes designs for Royal Doulton and Leslie Harradine modeled an unusual stoneware figure entitled I do believe in fairies.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

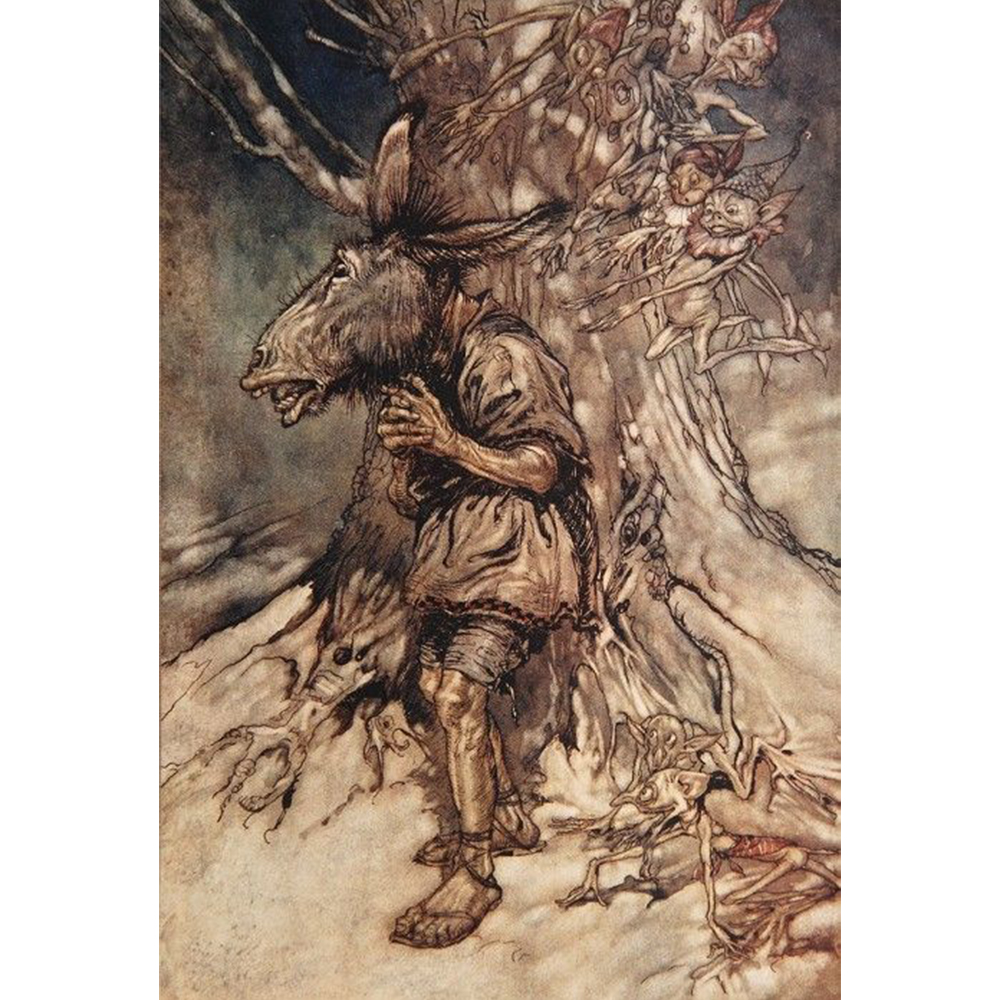

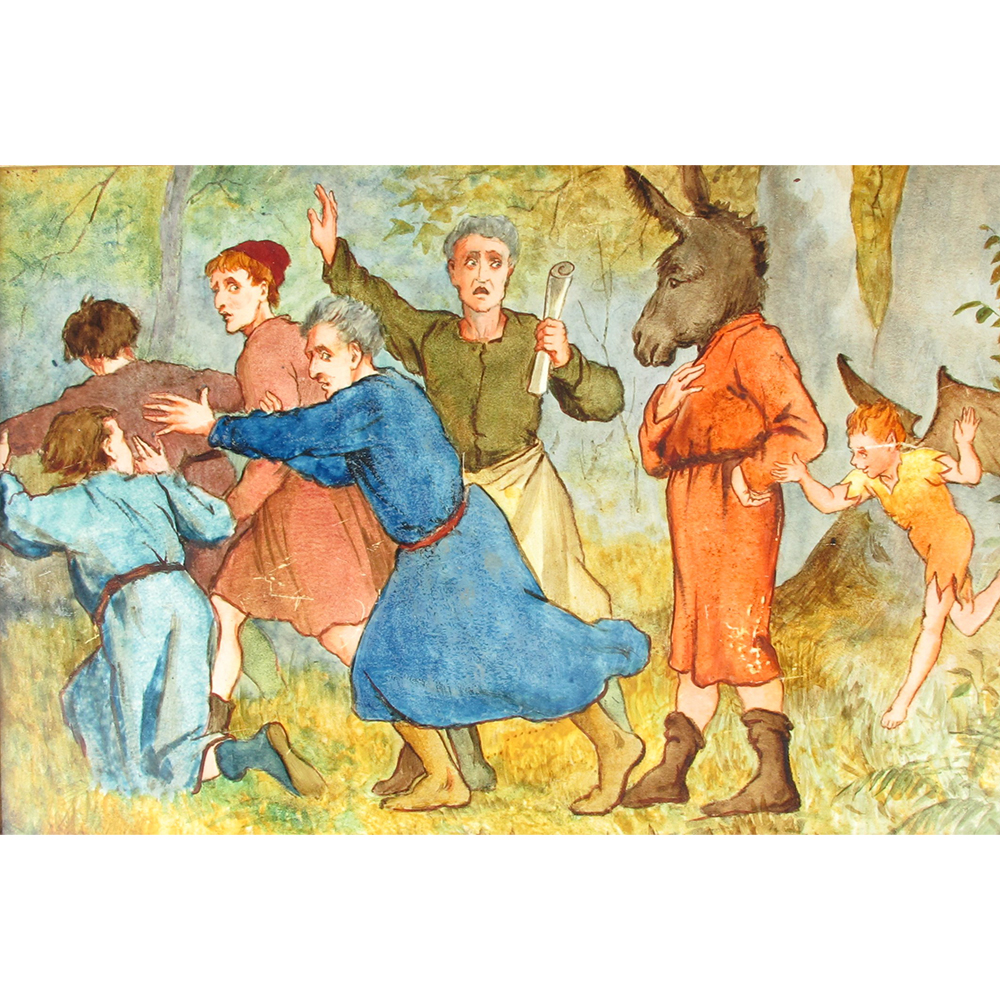

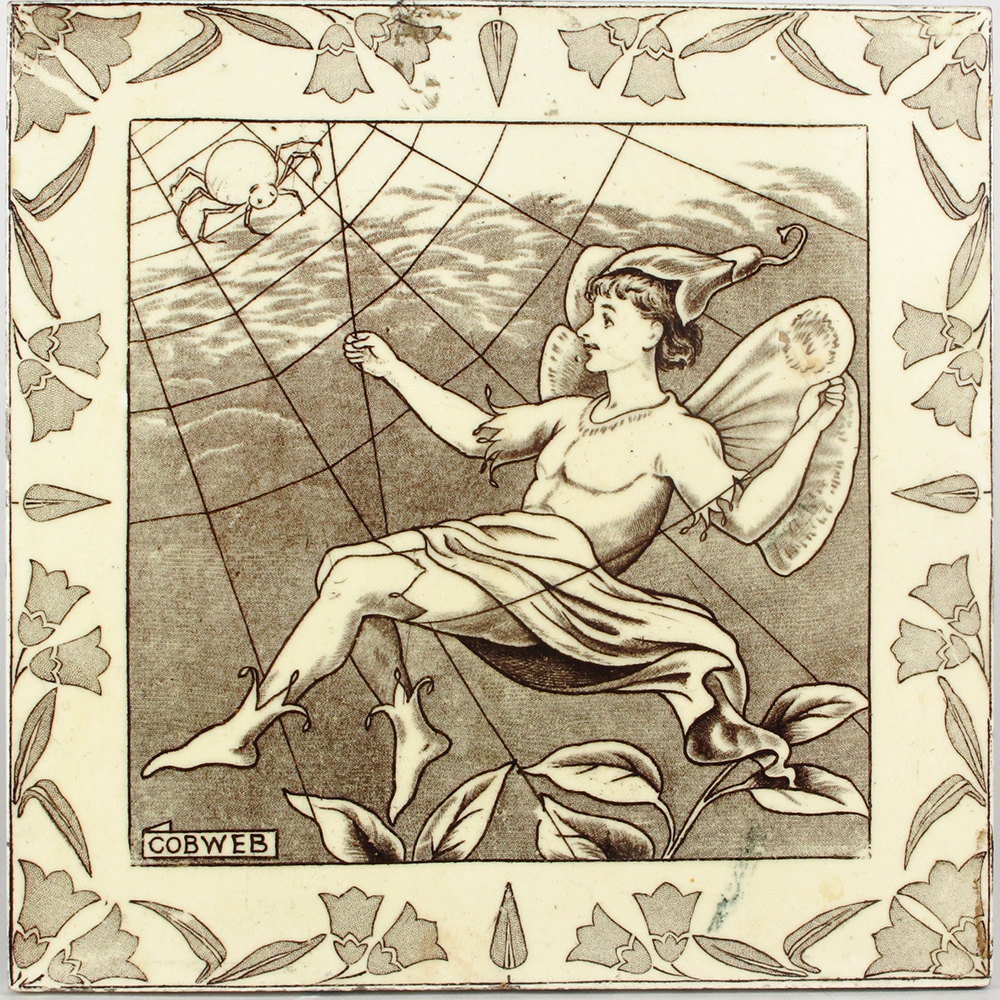

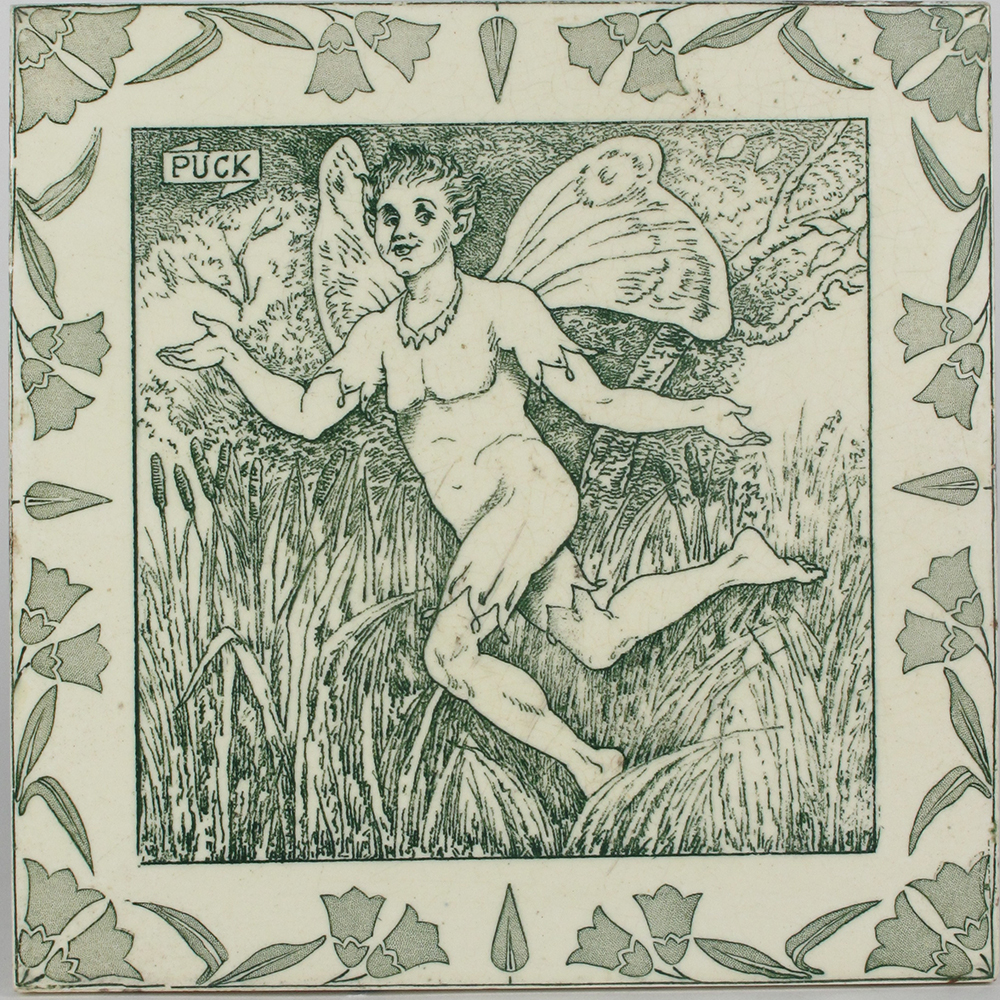

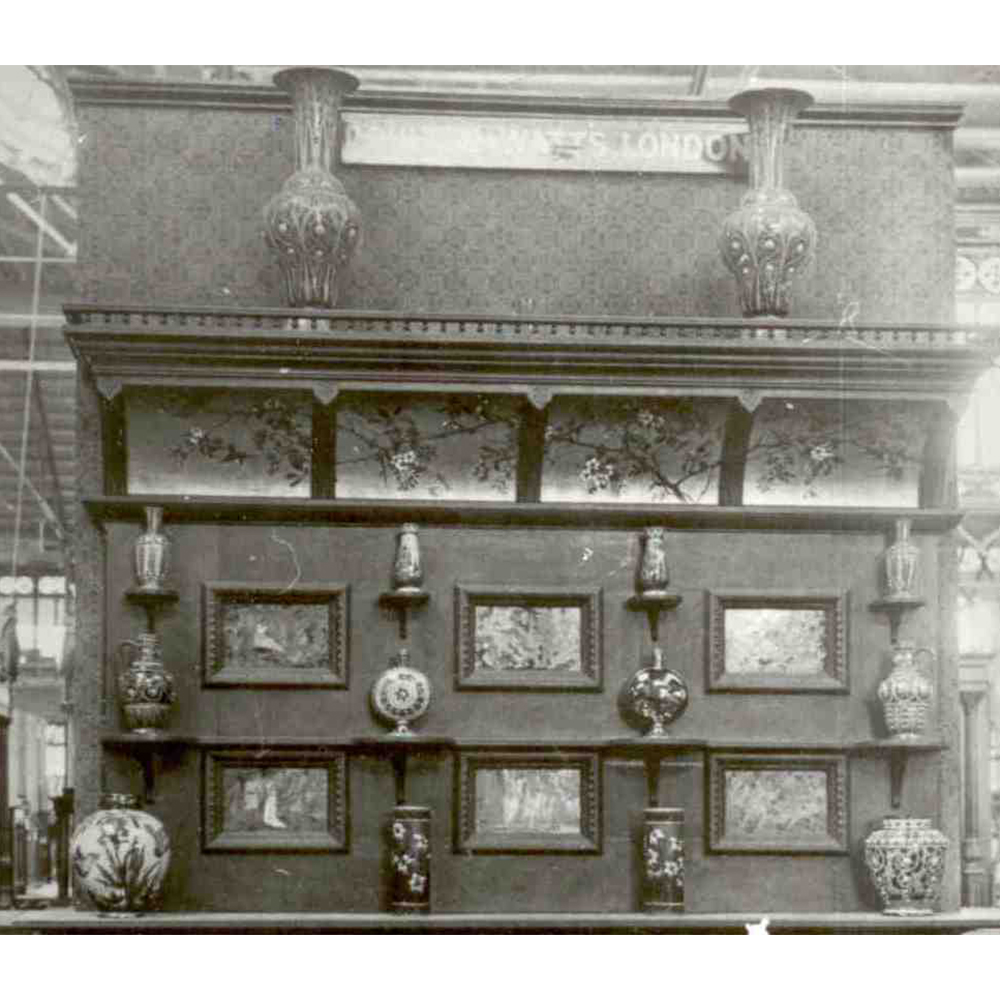

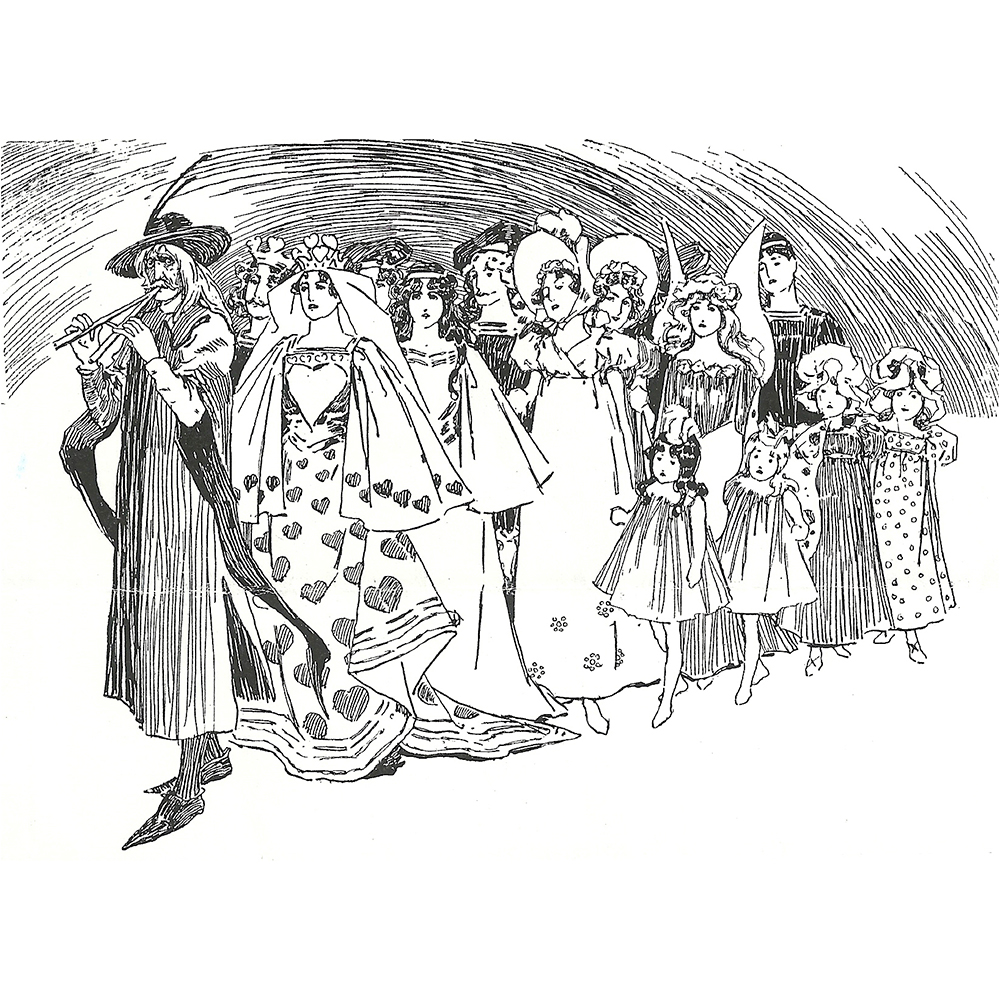

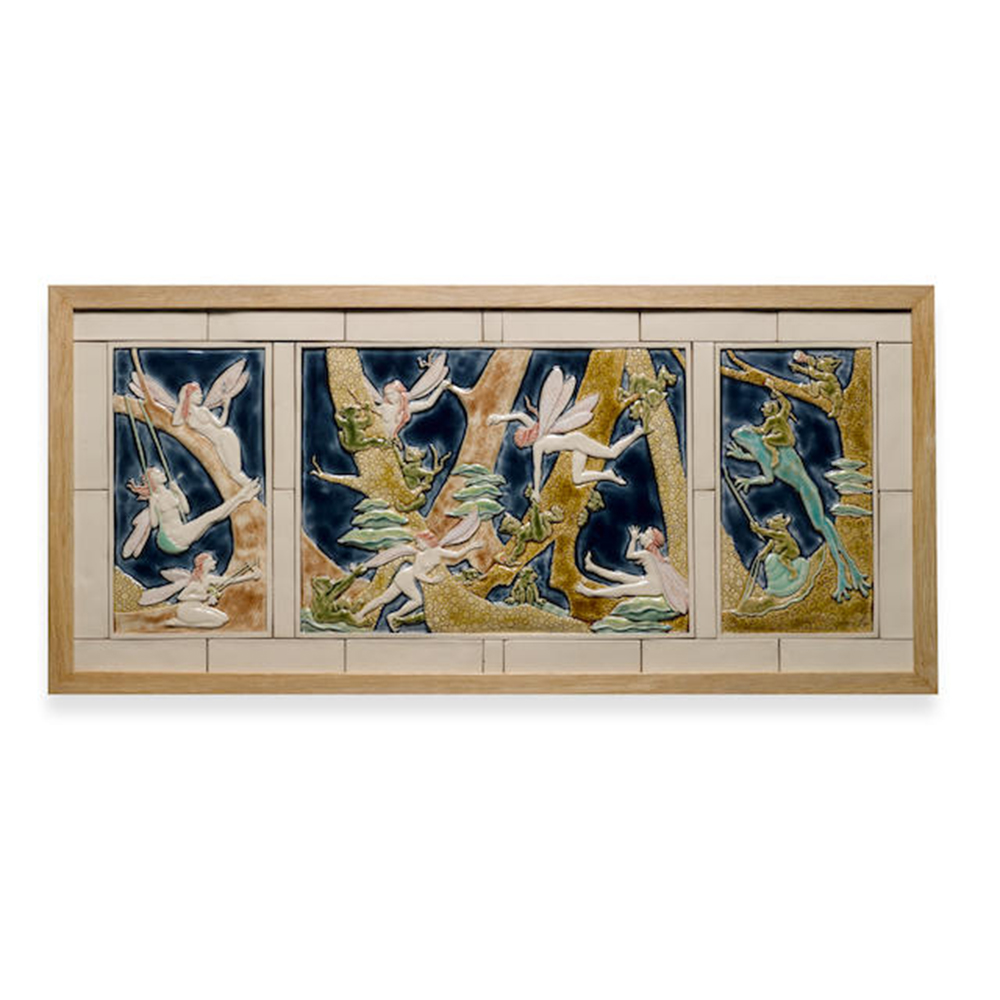

Fairy derives from the Latin goddess of fate. In old French romances, a fée was a woman skilled in magic. In English medieval folklore, a fairy was an ethereal, magical person, described as human in appearance. Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which was first performed in 1596, introduces us to Oberon and Titania, the King and Queen of the Fairies, and the capricious quick-witted Puck, who delights in playing pranks. His magic causes Titania to fall in love with a mortal called Bottom with the head of an ass. Shakespeare’s fairies were popular subjects on tile designs in the Victorian era and WMODA has a rare panel which was once incorporated in a Shakespearean mantlepiece at the Philadelphia exhibition in 1876.

A Rainbow of Fairy Books

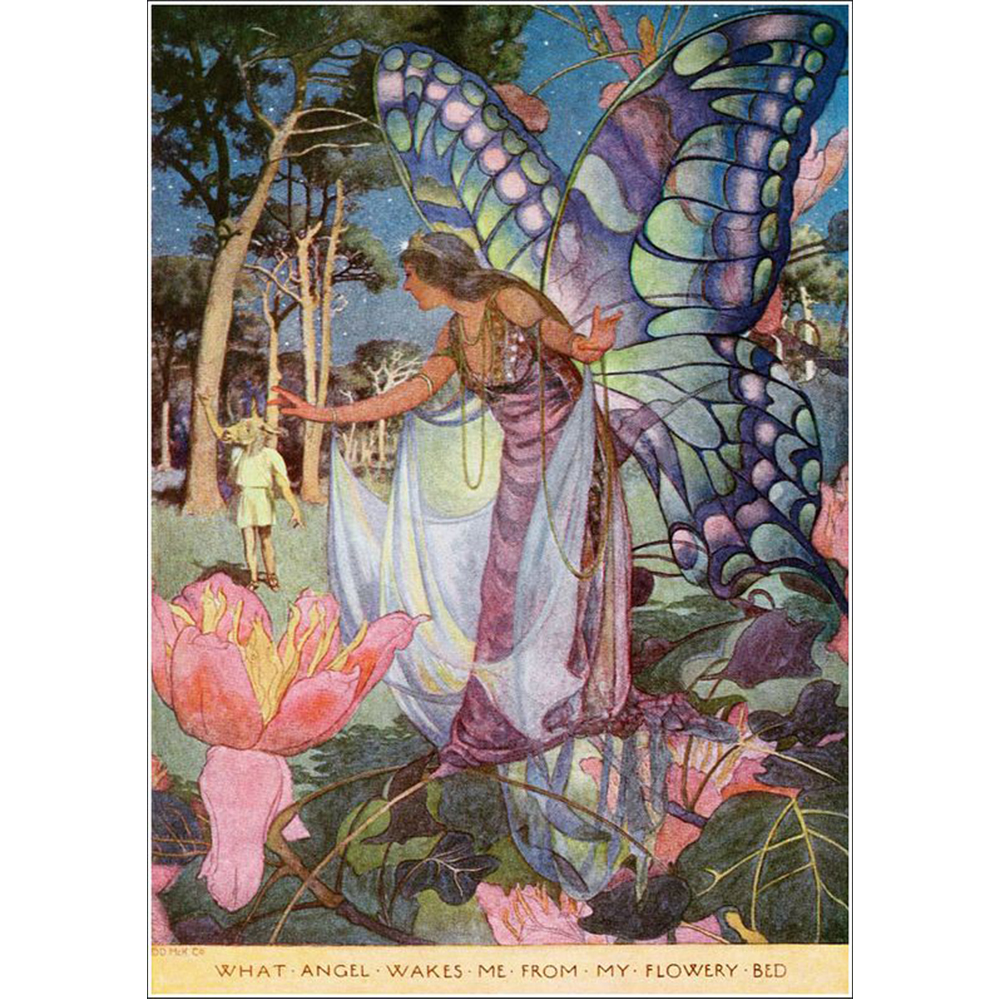

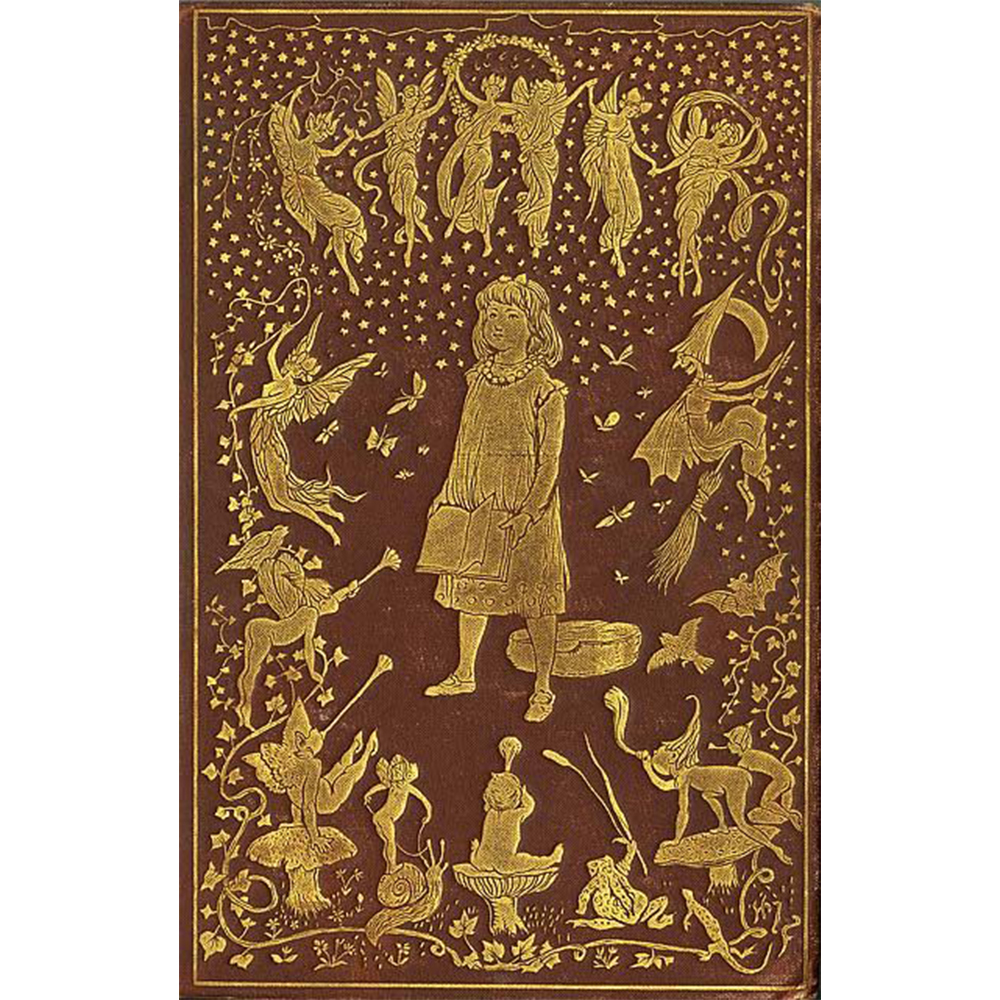

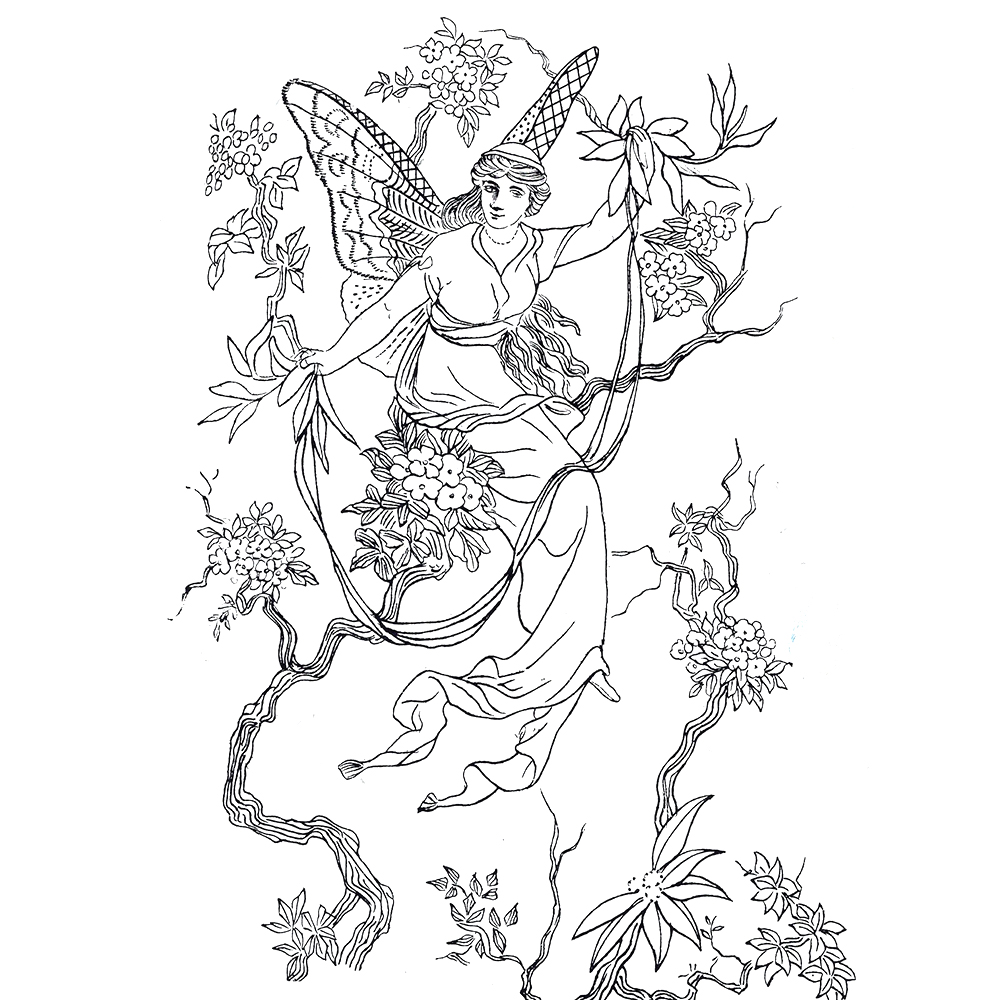

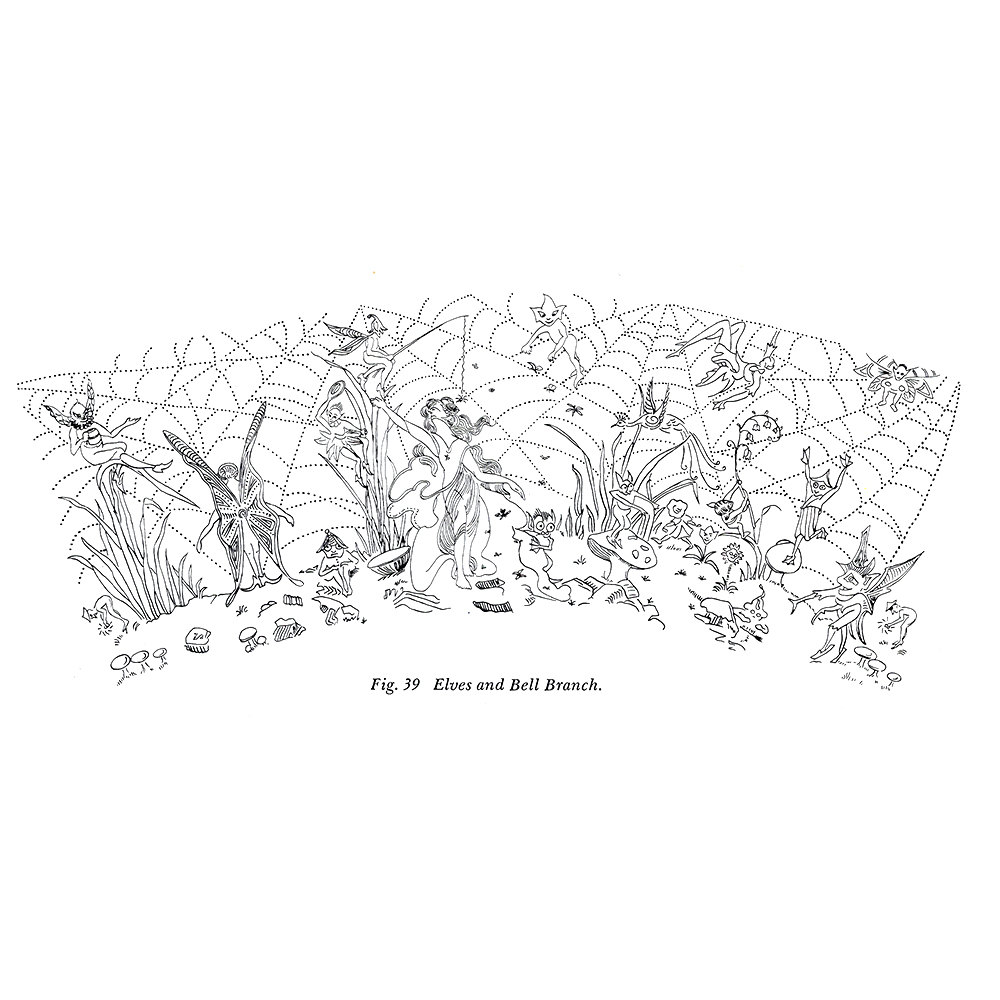

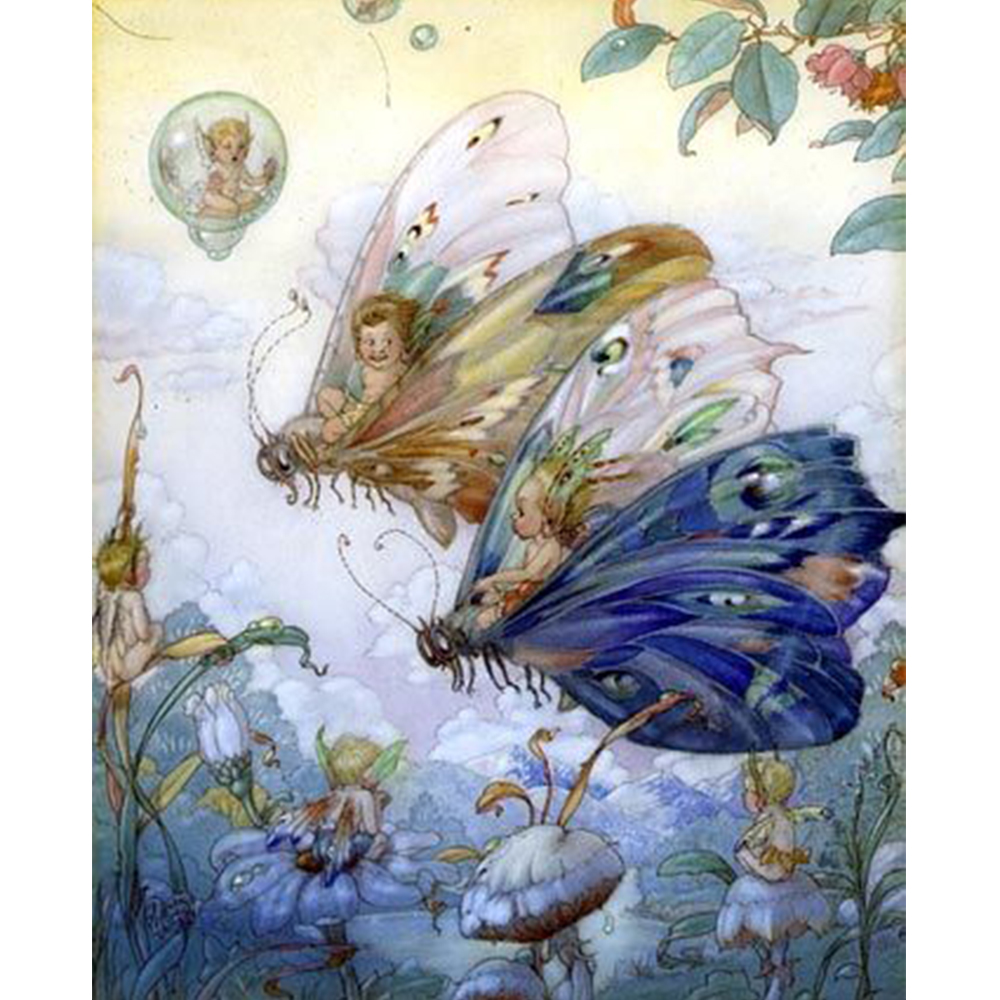

By the Victorian era, fairies were usually diminutive with butterfly wings as can be seen in the illustrations for Andrew Lang’s series of Rainbow Fairy Books, which were published between 1889 and 1910. In all, 437 fairy tales from around the world were published by the Scottish poet and folklorist and his 12 Rainbow Fairy Books were a huge influence on Daisy Makeig Jones and her Fairyland Lustre collection for Wedgwood. However, pretty fairies are rare in Daisy’s designs and she is better known for portraying the darker side of Fairyland as can be seen in our new Fantastique video.

The Celtic Twilight

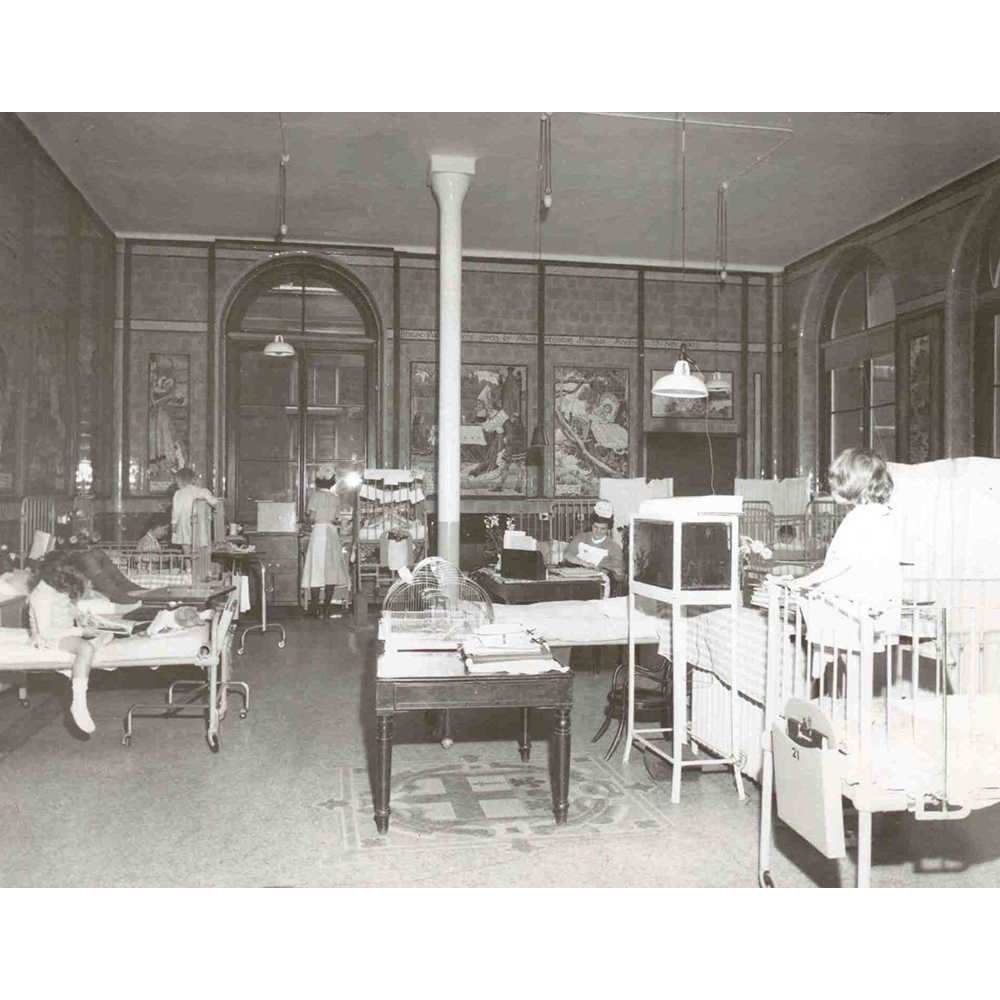

The Celtic Revival of the late 19th century also renewed interest in the world of Faerie for adults and children alike. Doulton’s Lambeth studio responded with beautiful Faience flower fairy vases designed by Margaret Thompson. Miss Thompson was also a talented book illustrator and she designed many Royal Doulton tile murals of fairy tales and nursery rhymes to decorate the children’s wards of hospitals in the early 1900s. Philanthropists of the period often donated these panels in memory of loved ones and a well-endowed hospital, such as St. Thomas’ in London, had scores of enchanting murals to entertain young invalids confined to their cots.

Once upon a time

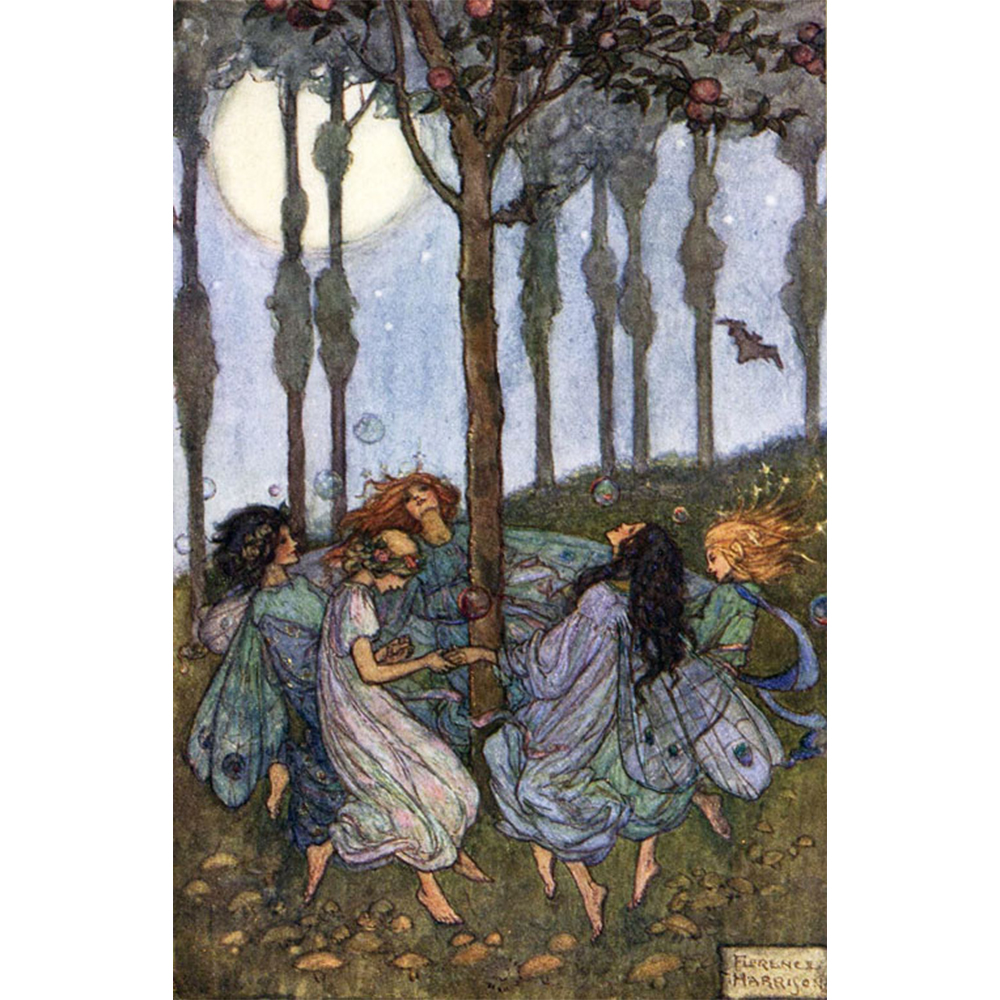

Many female illustrators established their reputations with fairy art in children’s books, which was considered an appropriate career for women. Depicting charming bedtime stories was identified with women’s maternal instincts as opposed to life drawing for ‘fine art’ which was not considered lady-like. Florence Harrison, Anne Anderson, Margaret Tarrant and Cicely Mary Barker were among the most talented artists in the UK who became famous for their fairy illustrations. In the USA, Jessie Willcox Smith was one of the highest paid illustrators of her time. Her work is still well-known today thanks to reprints of her illustrations, for example the 1905 edition of Robert Louis Stevenson’s A Child Garden of Verses. These poems about darkness and solitude, in particular The Little Land, inspired the Royal Doulton figure of the same name which depicts a child dreaming about all the little people in fairyland.

The Coming of the Fairies

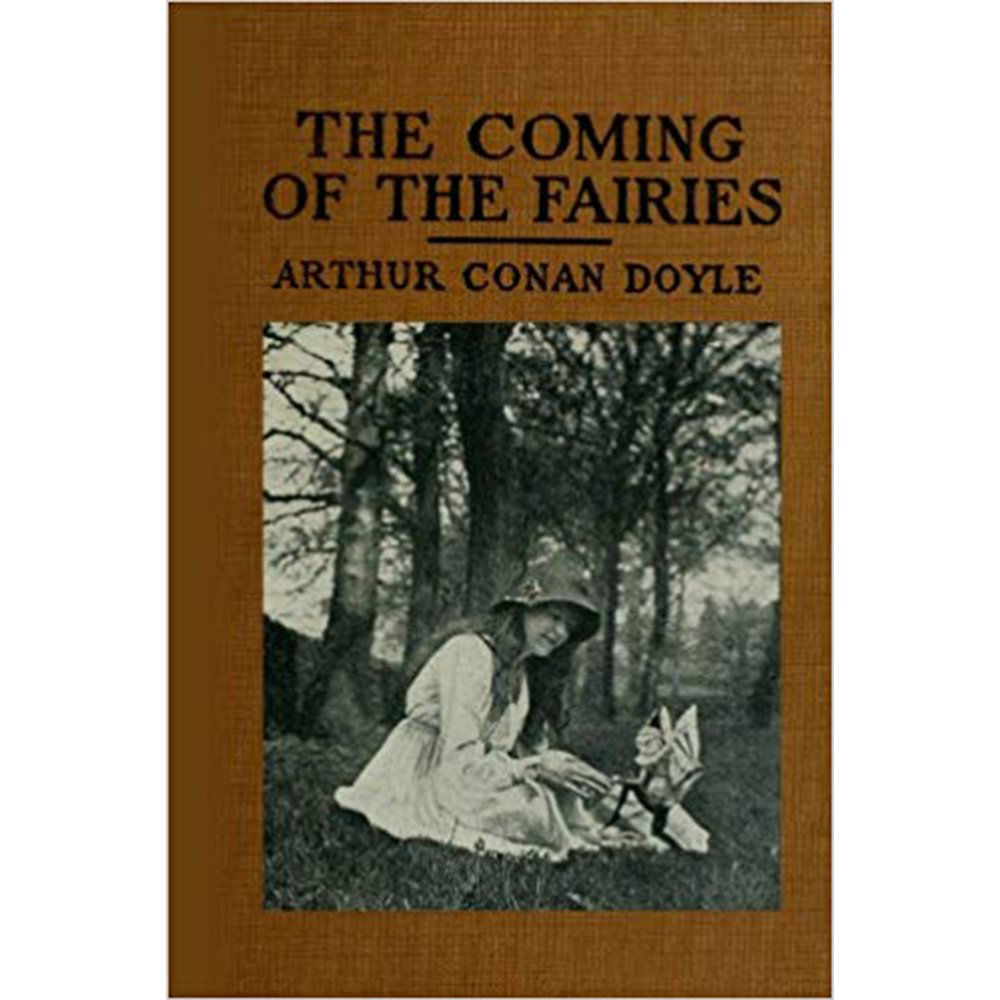

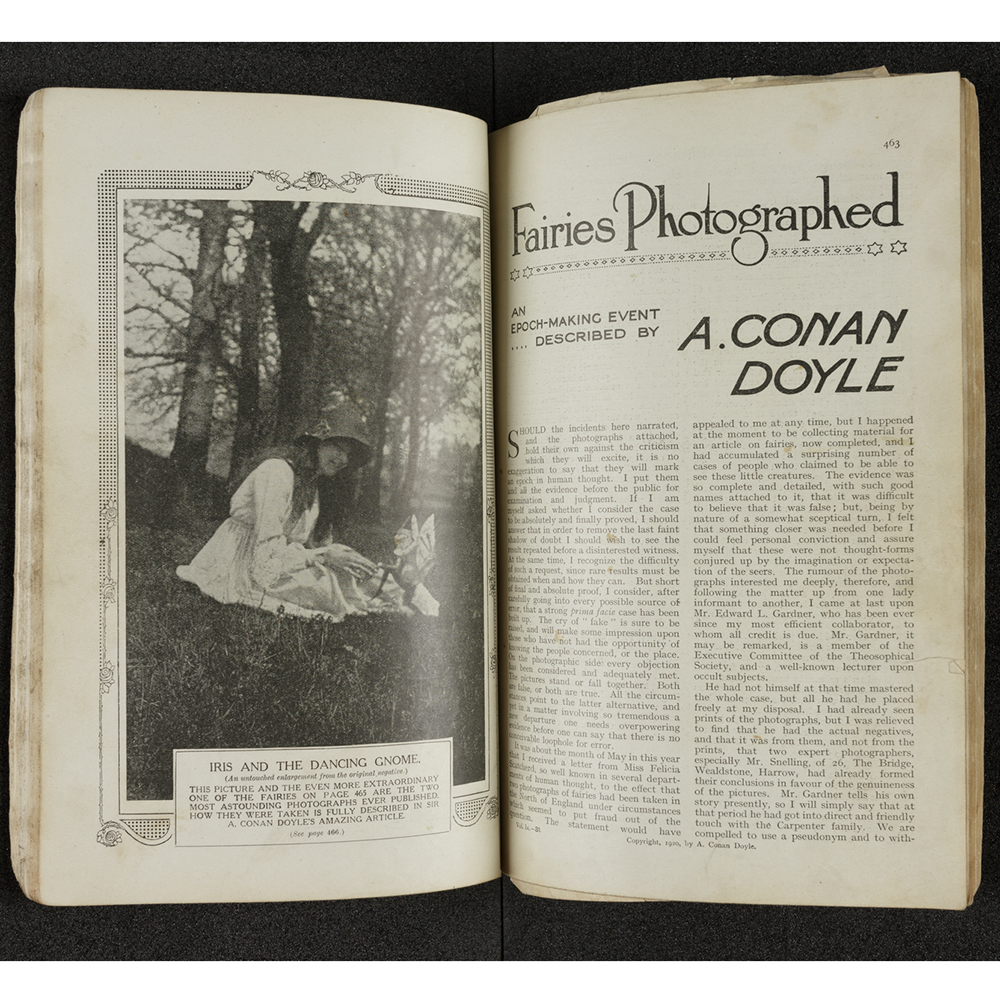

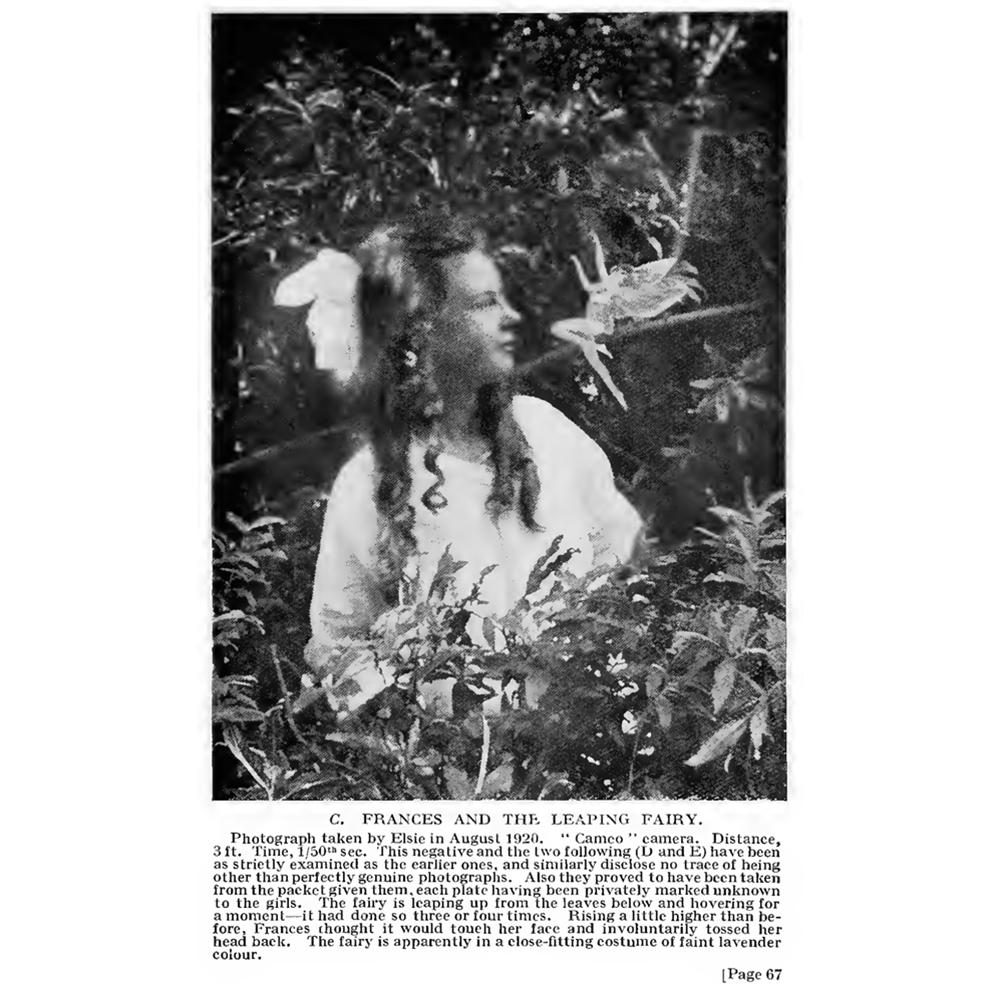

It was not just children who were fascinated by fairies particularly during the trauma of the First World War. Spiritualist and theosophy movements encouraged belief in fairies along with other types of psychic phenomenon. The existence of fairies was ‘proven’ in the 1920s with the famous hoax of the Cottingley photographs which purported to show fairies dancing at the bottom of the garden. The ‘fairies’ were photographed in 1917 by two girls, Elsie Wright and her cousin Frances Griffiths. The case received international acclaim through Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the author of Sherlock Holmes, who was fascinated by the account and wrote an article for the Strand Magazine in 1920. In The Coming of the Fairies, which was published two years later, he featured fairy sightings all over the world.

Fairy Tale · A True Story

With the world’s attention focused on them, the Cottingley girls had little option but to stick to their story and did not confess until the 1980s that they had photographed cut out illustrations by Claude Shepperson from Princess Mary’s Gift Book. The hoax photos continue to fascinate us today as evidenced by the 1997 movie Fairy Tale - A True Story and vases by the Moorcroft pottery. Last month two of the photographic prints, which could be purchased at Edward L. Gardner’s theosophical lectures in the 1920s, sold at auction in the UK for a phenomenal £20,000.

Do you wonder where the fairies are?

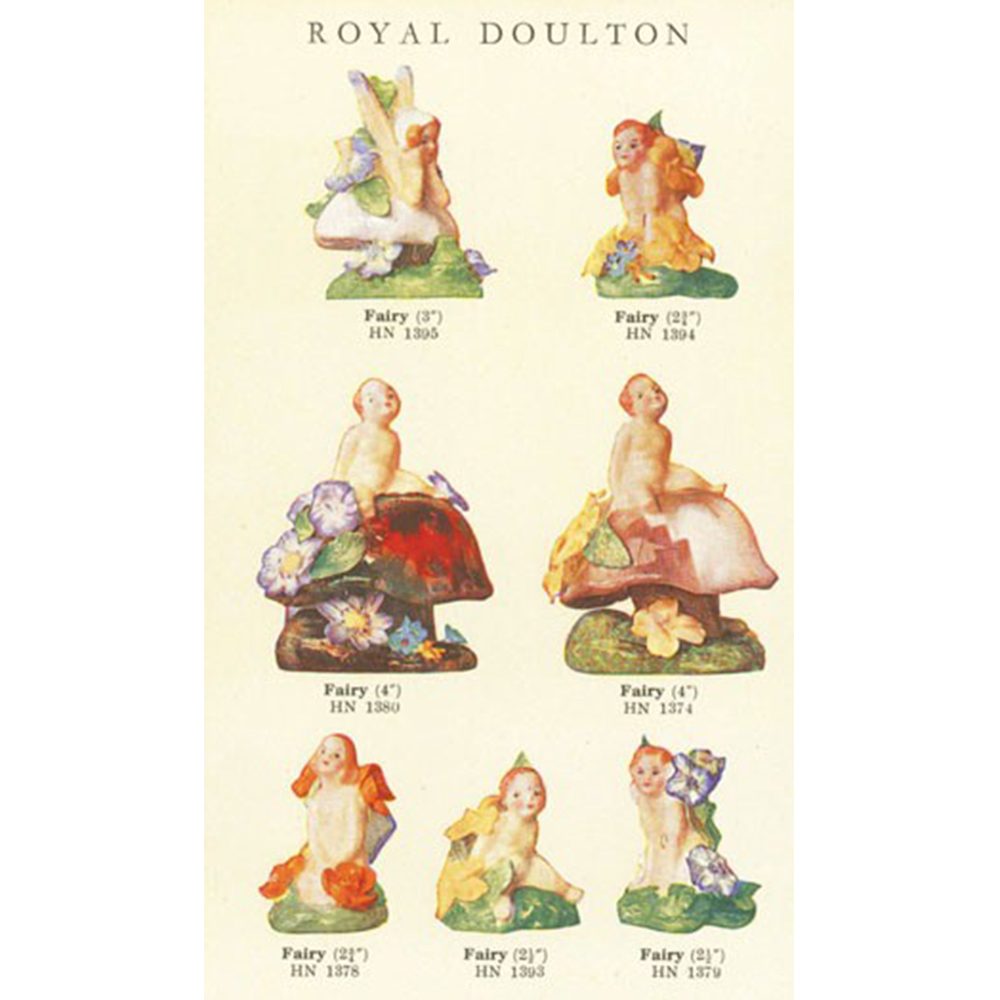

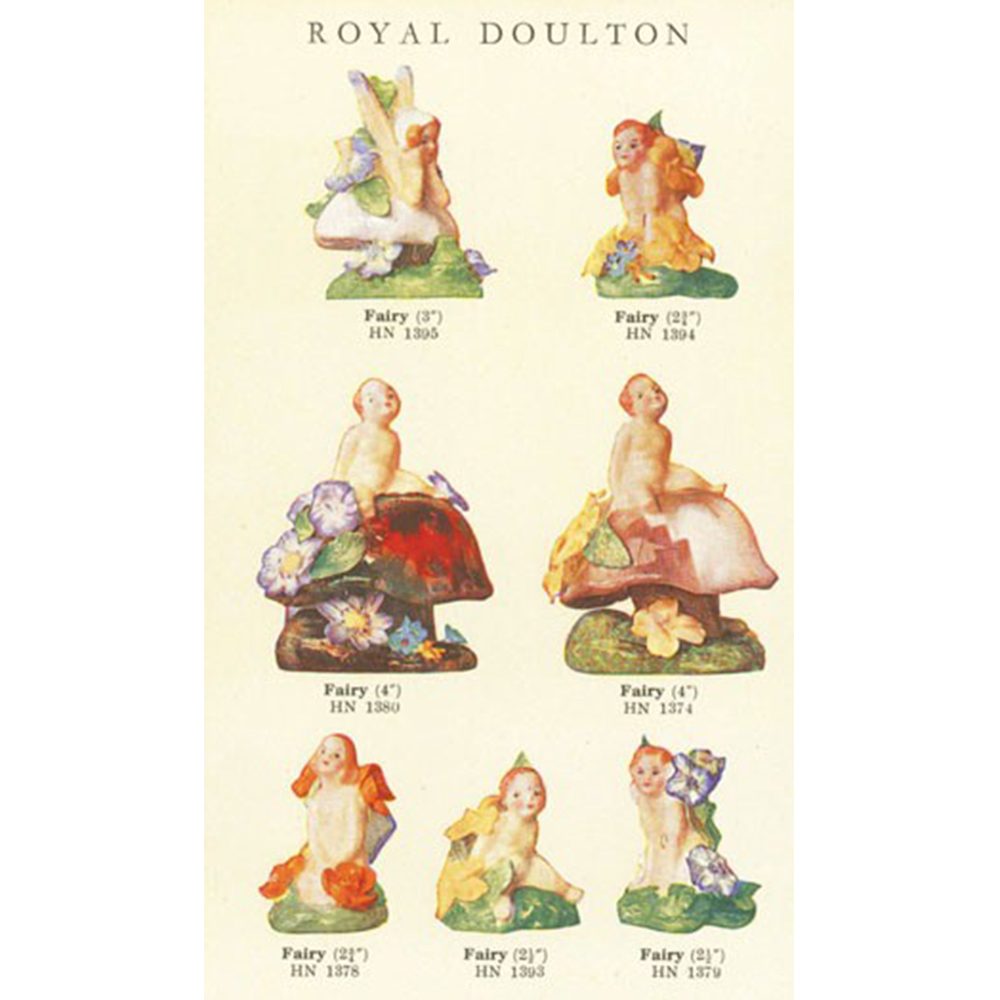

The juvenile prank grew into a mass media circus during the 1920s. Royal Doulton responded to this new fairy phenomenon with a beautiful collection of fairies cavorting amongst flowers and toadstools modeled by Leslie Harradine. Six different models of fairy figures were accessorized with different flowers, assembled petal by petal and decorated in a variety of colors. Production of the fairy collection ceased in 1938 making these fairies almost as elusive as their fantasy friends, a sentiment echoed by Harradine’s child study of 1933 entitled Do you wonder where the fairies are that folk declare have vanished?

Fairy Aviators

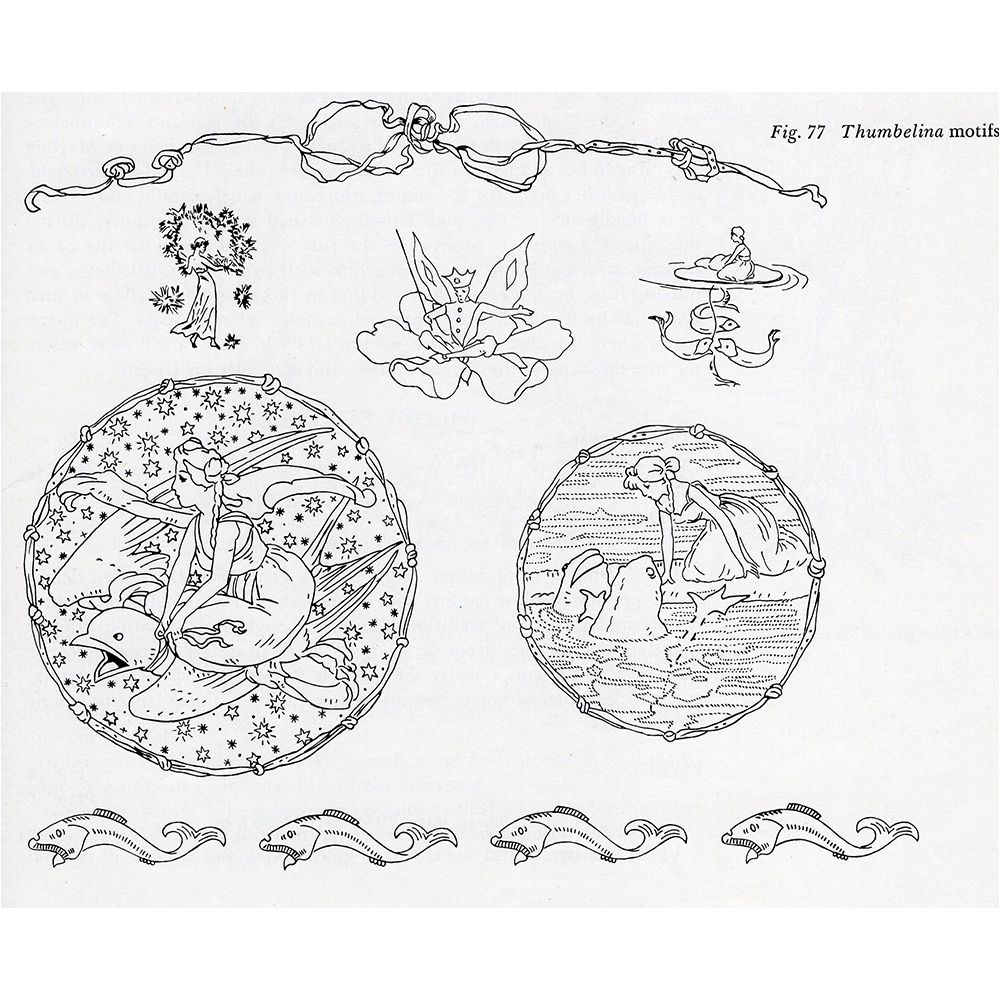

Not all fairies have wings as can be seen in Harradine’s models. Some need help to fly from their friends in the insect world. Fairy art abounds with images of fairy aviators, as can be seen in the illustration by Harold Gaze, who was known as the Bubble Man from his tendency to feature fairies in bubbles. A striking 1875 Minton plaque by Boullemier in the Fantastique exhibit shows a fairy swooping through the air on a butterfly. In the 1920s, the Rosenthal factory featured little folk on the backs of dragonflies and grasshoppers while Thumbelina by Charles Vyse is transported by a toad.

In more recent years, Victoria Ellis has revived the enchanted world of ceramic art with her relief-modeled and hand-painted panels representing the denizens of fairyland and the wonders of the deep.

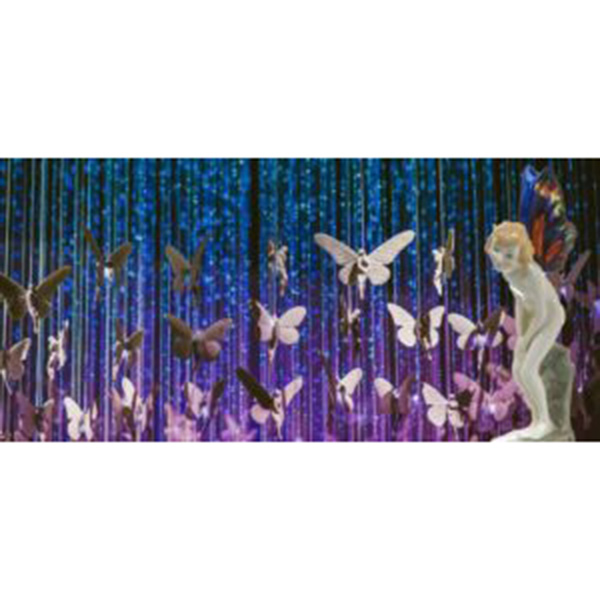

Visit our Fantastique exhibit to discover more about Fairyland in ceramic art and don’t miss the stunning Lladró Niagara chandelier which hangs at the entrance to the Gallery of Amazing Things on the first floor.

Related Stories

Peter Pan Rackham

Peter Pan Rackham

Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens

Gnomes Royal Doulton

Doulton I do believe in fairies

Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens

Titania Doulton Lambeth H. A. Miles

Bottom Midsummer Nights Dream Rackham

Bottom Doulton Lambeth 1875

Anna Pavlova

Moth

Peter Pan Rackham

Puck

Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens

Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens

Anna Pavlova

Fairyland Lustre Case

Wedgwood Butterfly Woman

Fairyland Lustre Case

Leapfrogging elves & elves on branch

Detail Doulton Bluebells Fairy

Margaret Thompson

Daffodil Fairy M Thompson

Margaret Thompson Fairy Bluebells

M. Thompson

Fairies at Christening

Seymour St Thomas

The Little Land Royal Doulton

Cicely Mary Barker

Florence Harrison Elfin Song

Florence Mary Anderson

Sleeping Beauty Margaret Tarrant

Coming of Fairies

Strand Magazine

Coming of Fairies

Cottingley Fairies

Royal Doulton Flower Faires

Royal Doulton Flower Faires

Royal Doulton Flower Faires

Royal Doulton Fairies catalog page

Royal Doulton Fairies catalog page

Butterfly Fairy

Rosenthal

Fee du Printemps

Rosental Gliding Flight Caasmann

Margaret Tarrant

The Faeries torment the Tree Imps Ellis

Thumbelina

Fairy Aviators H. Gaze

Fairy and Butterfly

Boullemier Minton 1875

Niagara chandelier