By Louise Irvine

Ancient Egypt inspired the Art Deco Day celebration in Florida this year during the World Congress. Not surprisingly, there were many reincarnations of Egyptian pharaohs including Cleopatra and Tutankhamun. The discovery of King Tut’s tomb in 1922 led to an Egyptomania craze during the Art Deco era. However, a fascination for Queen Cleopatra preceded the Roaring Twenties and she is one of the most alluring femmes fatales featured in the Fired Arts.

To the ancient Egyptians, Cleopatra was the incarnation of the goddess Isis, the role model for all women as a mother and a healer. Her magical powers transcended all the other deities, and she was invoked on behalf of the sick and the dead. However, Cleopatra’s enemies believed her to be a ruthless seductress who was responsible for the downfall of her Roman lovers, Julius Caesar and Marc Antony. After Caesar’s assassination, Cleopatra named their son co-ruler of Egypt at the age of three and he was compared to the divine child Horus.

Cleopatra also had three children with Marc Antony but her love affair with Caesar’s general and successor ended in tragedy when she committed suicide with the bite of an asp. Shakespeare portrayed Cleopatra as a tragic heroine in a play first performed in 1607 and her legacy has continued in numerous dramatizations and works of art over the centuries.

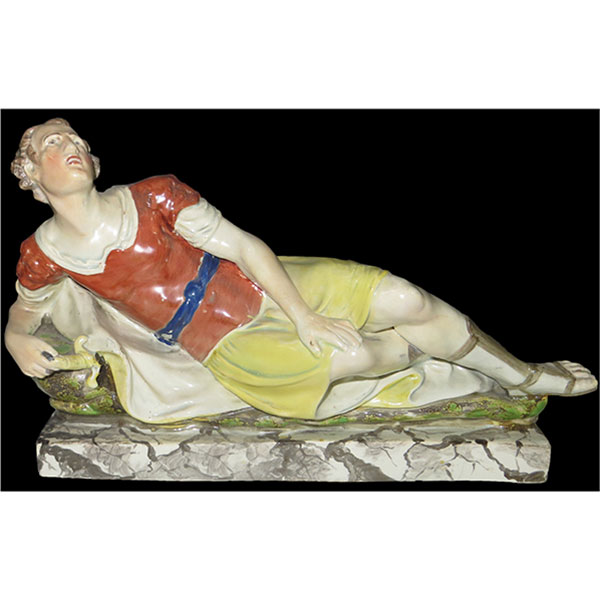

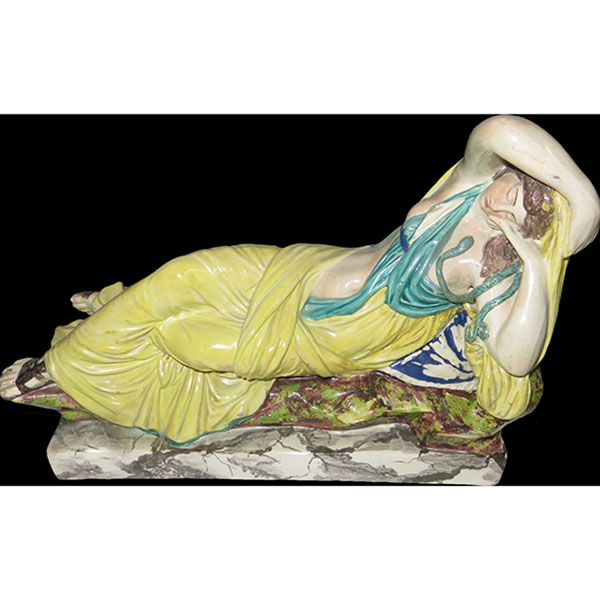

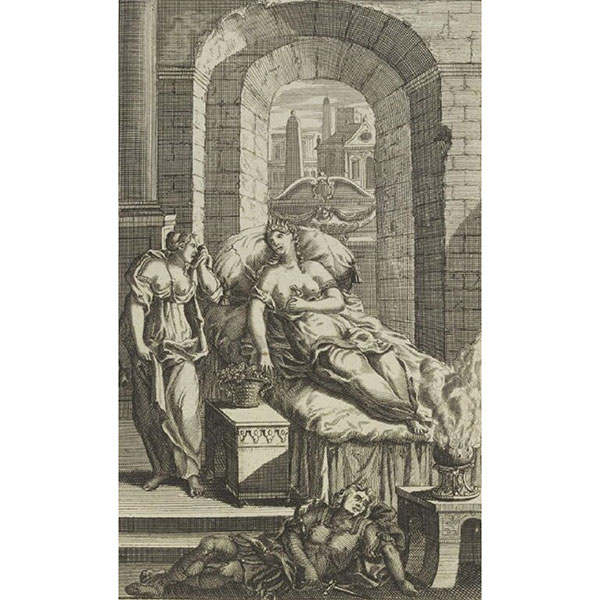

The earliest portrayal of Antony and Cleopatra at WMODA is a pair of enameled creamware figures from the late 18th century attributed to Ralph and Enoch Wood. Similar figures were made by other Staffordshire potteries in different color schemes. This portrait of Cleopatra was based on one of the most renowned sculptures of antiquity in the Vatican which was identified originally as the Egyptian queen because of the snake bracelet on her arm. Michael Vandergucht’s 1709 illustrations for Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra could also have been a source for the early Staffordshire potters.

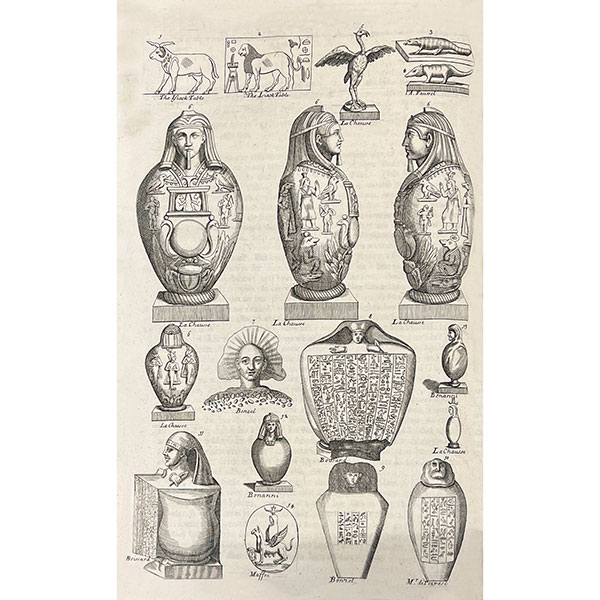

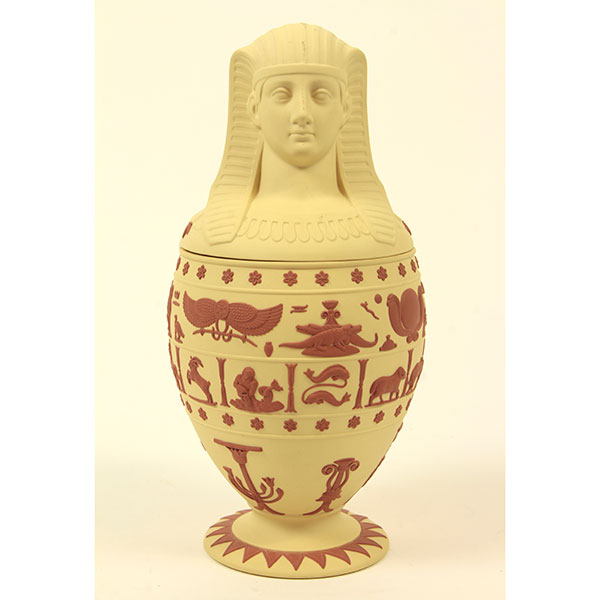

During the 19th century, the Wedgwood factory introduced several versions of Cleopatra in Black Basalt, Carrara, and Majolica ware. Egyptian motifs became popular in the decorative arts following Nelson’s naval victory at the Battle of the Nile in 1798. Wedgwood introduced a teapot with a crocodile motif and hieroglyphics as well as a jug depicting the Sphinx. Their most distinctive Egyptian design is the canopic jar which was produced in Caneware, Black Basalt and Jasperware in the mid-19th century and revived in the 20th century. These vessels were used during the mummification process and feature hieroglyphics and the head of the funeral deity, Imsety, a son of Horus.

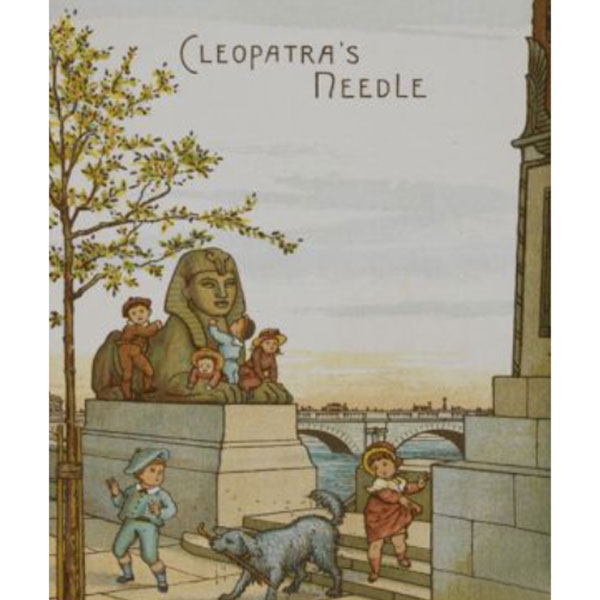

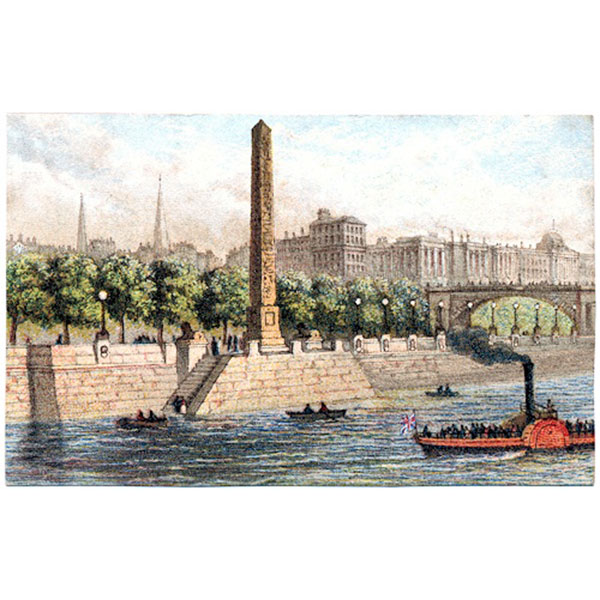

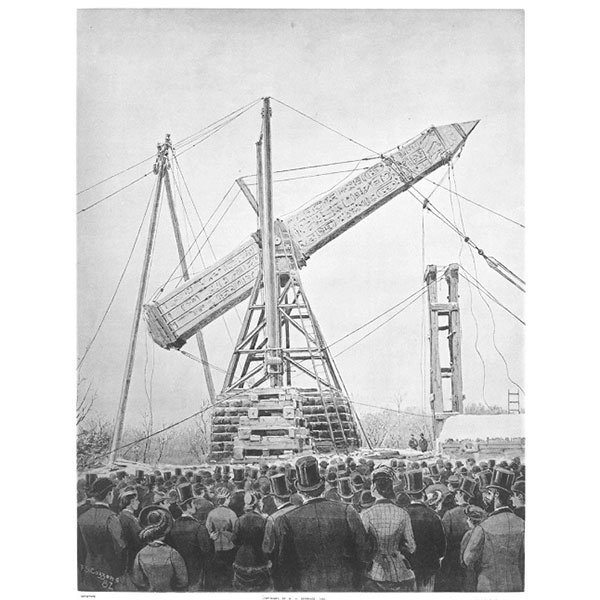

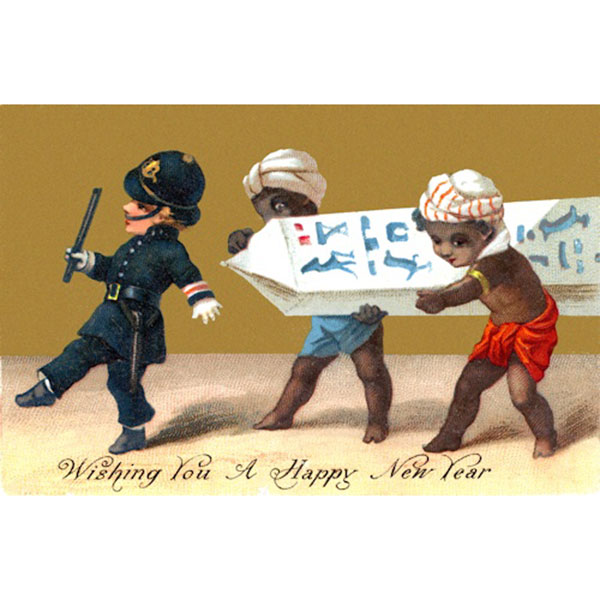

The public’s fascination with Egypt and hieroglyphics continued when Cleopatra’s Needles were erected in London and Central Park, New York in 1878 and 1881 respectively. These monuments to the pharaohs were built 3,500 years ago and were diplomatic gifts from the ruler of Egypt. Originally, the obelisks stood in Heliopolis but they were moved to Alexandria reputably by Cleopatra in memory of Julius Caesar. Time capsules were buried under both monuments and Doulton’s Lambeth factory provided the stoneware container for the London collection which included a portrait of Queen Victoria and 12 English beauties of the day. Copies of the Bible were added to both time capsules and the American one also included the complete works of Shakespeare and the Declaration of Independence.

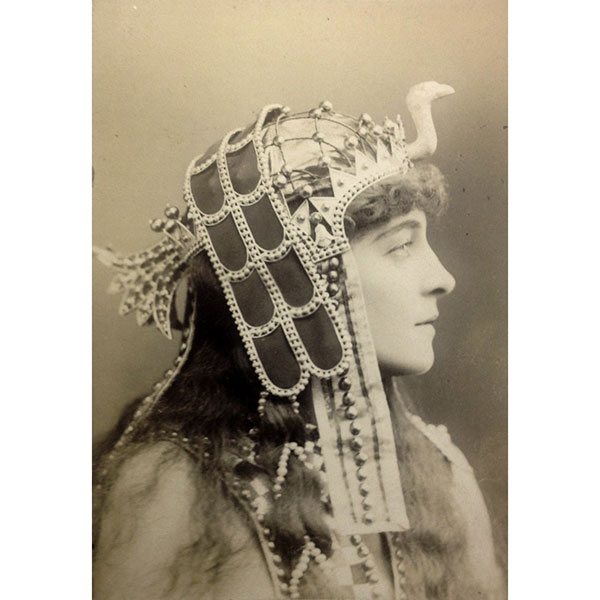

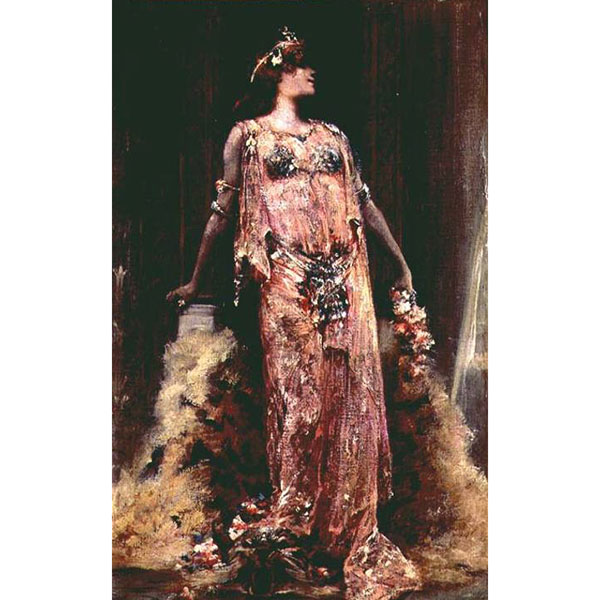

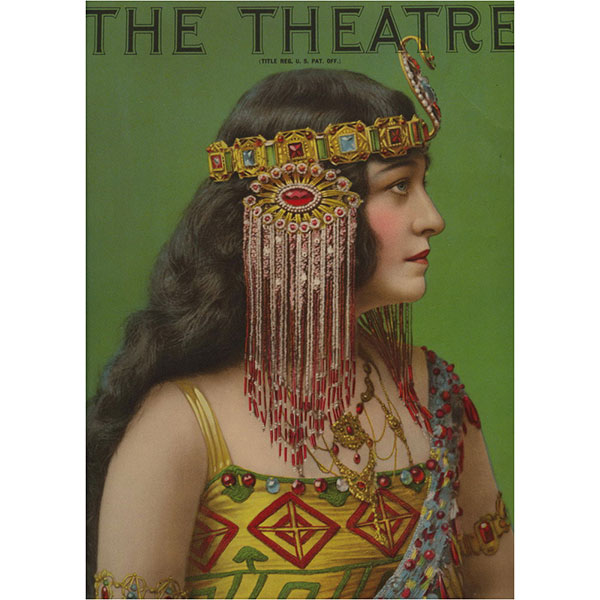

Several famous Victorian actresses starred as Cleopatra in the late 19th century and created the image of the Egyptian queen as a sultry femme fatale. Sarah Bernhardt, the actress and courtesan, beguiled her way across the stages of Paris, London, and New York and enhanced Cleopatra’s reputation as a dazzling seductress in Sardou’s play in 1890. The “divine Sarah” kept two live garter snakes to play the role of the poisonous asp in her melodramatic performance. Cleopatra was also portrayed on stage by Lillie Langtry, the vivacious blonde vixen who captivated London high society and became a mistress of the Prince of Wales. Photo cards of the two stars inspired Charles J. Noke to model a figure of Cleopatra for his new series of ivory glazed porcelain known as Vellum.

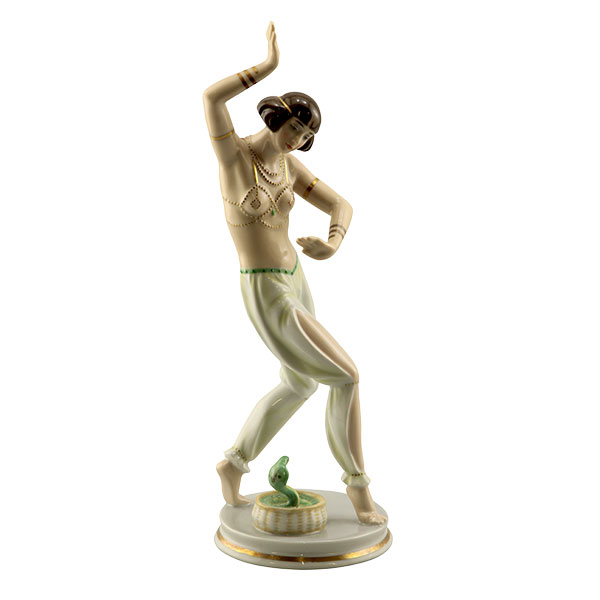

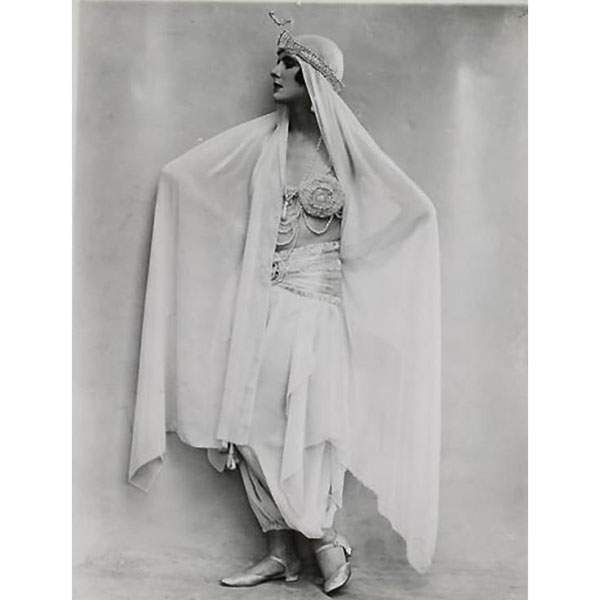

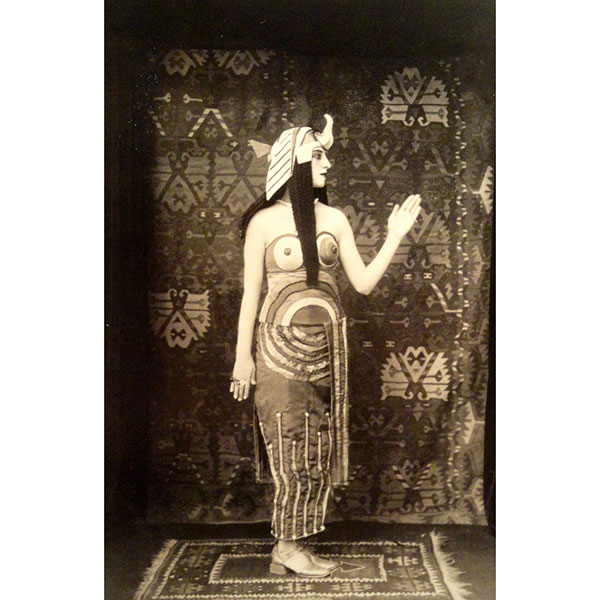

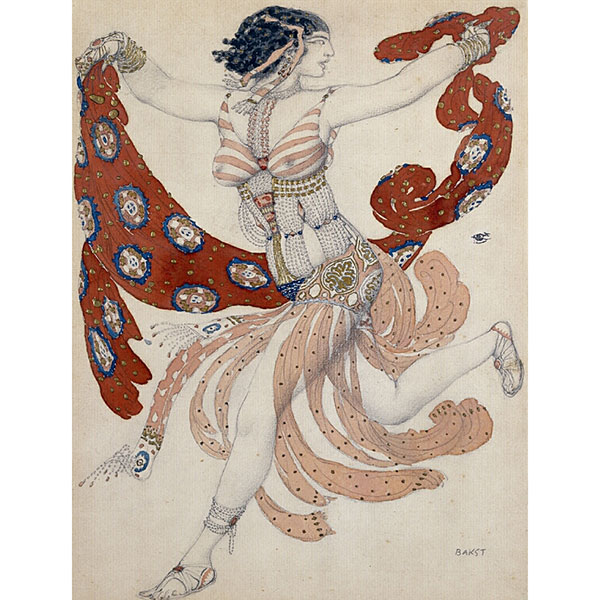

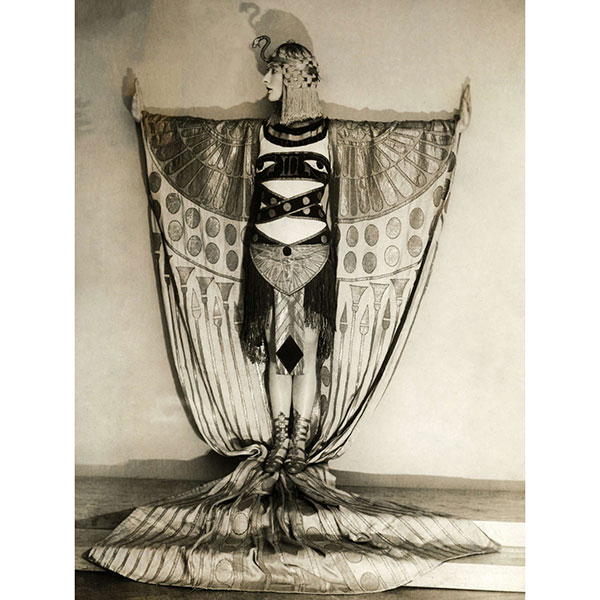

Cleopatra caused a sensation on the European stage when the Russian dancer, Ida Rubinstein, appeared as the Egyptian queen with the Ballet Russes in 1909. Miss Rubinstein caught the attention of Diaghilev, the Russian dance impresario, the previous year when she stripped naked during a private performance of Salome’s Dance of the Seven Veils. Her horrified family briefly committed her to a mental asylum but she married a cousin to earn her freedom to perform. Her sumptuous Ballet Russes performances in Cleopatra and Scheherezade, wearing costumes designed by Leon Bakst, set a trend for Orientalism and exotic sensuality in fashion and design during the early 1900s.

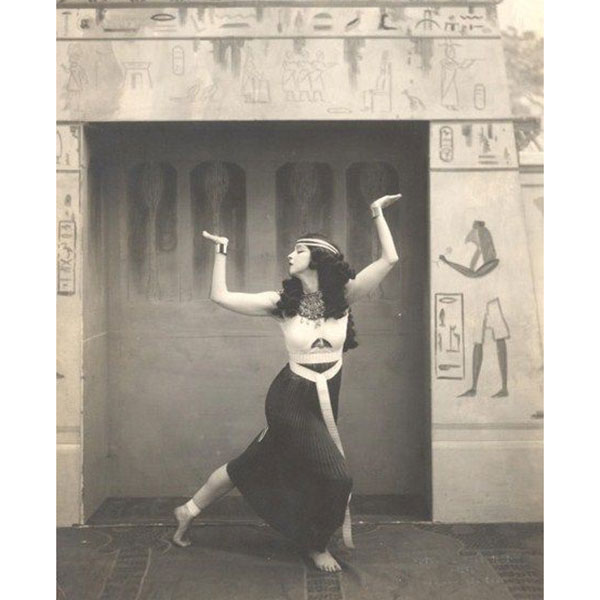

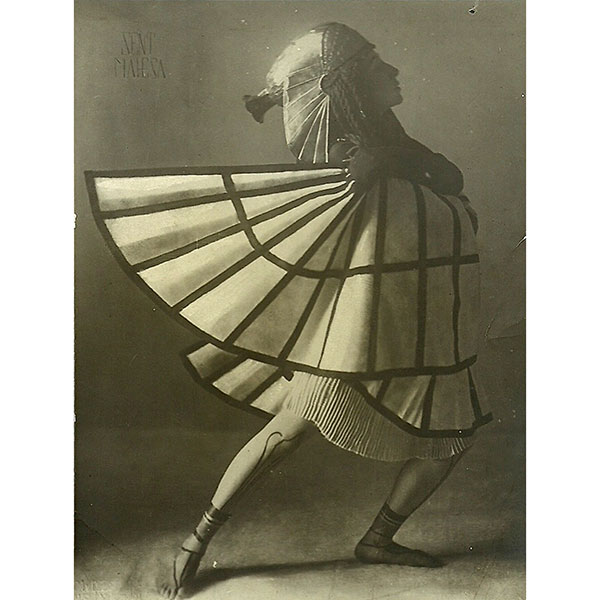

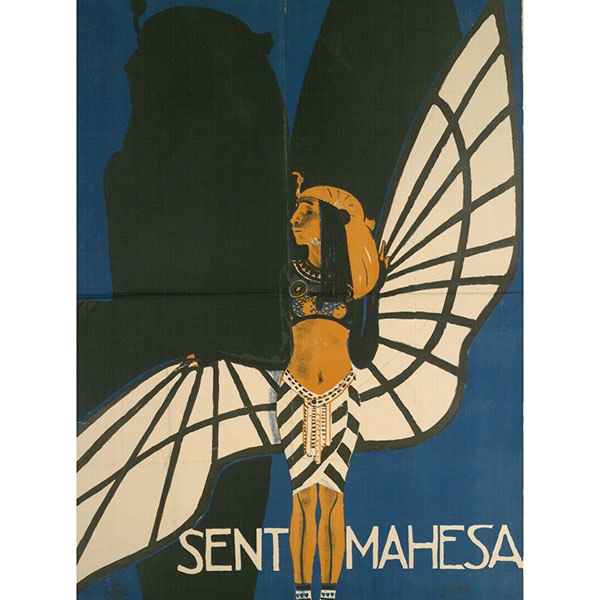

Exotic dances were also the specialty of a young Swedish dancer, Else von Carlberg, known on stage as Sent M’ahesa. She moved to Berlin to study Egyptology and performed her first program of ancient Egyptian dances in 1909. At the same time, the American dancer, Ruth St. Denis, toured Europe with similar dances. Sent made all her own costumes, covered herself in ochre body paint, and adopted profile poses reminiscent of Egyptian tomb paintings.

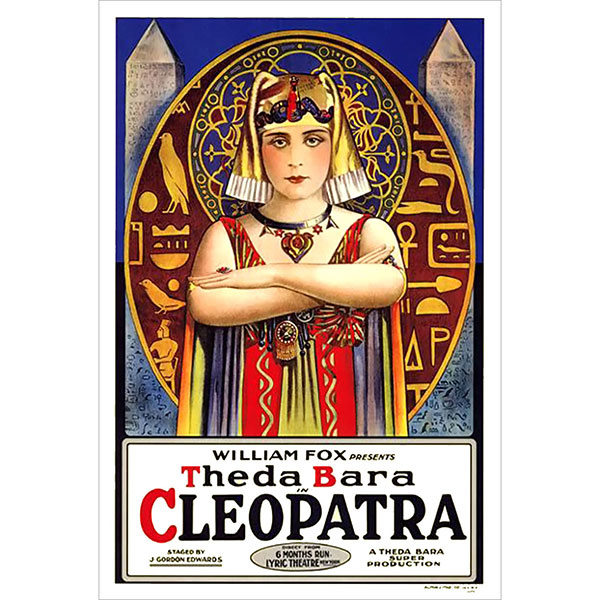

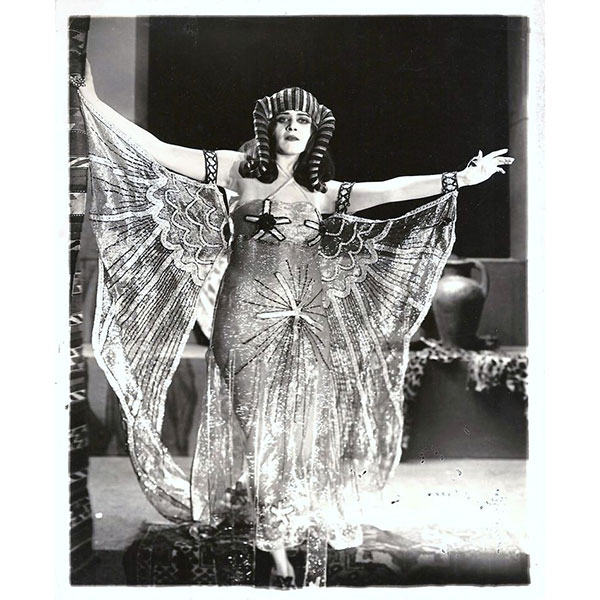

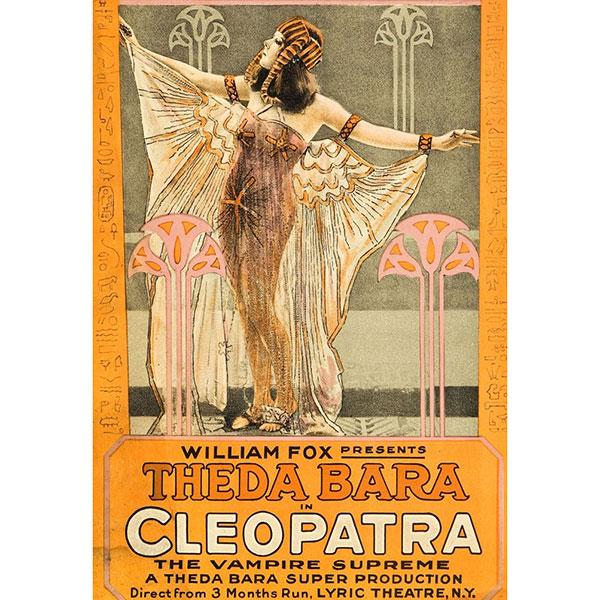

Cleopatra became one of the cinema’s first sex symbols thanks to Theda Bara, the original vamp. The name was coined after she played a seductive vampire in a 1915 silent movie. Her portrayal of Cleopatra in 1917 was described as “obscene” because of her risqué, nearly nude outfits and church organizations tried to destroy the film. Unfortunately, only 40 seconds of the film remain after a fire at Fox studios. Born Theodosia Goodman in Ohio, Theda for short, her stage name was rumored to be an anagram for Arab Death and it was claimed she grew up in the shadow of the Sphinx. Her exotic looks with smoldering, heavily kohled eyes became a trademark for the Hollywood movie vamps.

The Goldscheider studio in Austria produced some of the most striking Art Deco figures and their Egyptian Dancer, also known as Aida, depicts the dancer, Lore Wigand, modeled by Josef Lorenzl from a 1916 photograph. Launched in 1922, the year King Tut’s tomb was discovered by Howard Carter, this popular statuette was hand-painted in several striking color schemes.

Discover more about these sultry Egyptian beauties in the Flappers, Vamps & Divas exhibition when WMODA reopens in Hollywood.

For information on Art Deco in Florida visit the Art Deco Society of the Palm Beaches and the Miami Design Preservation League.

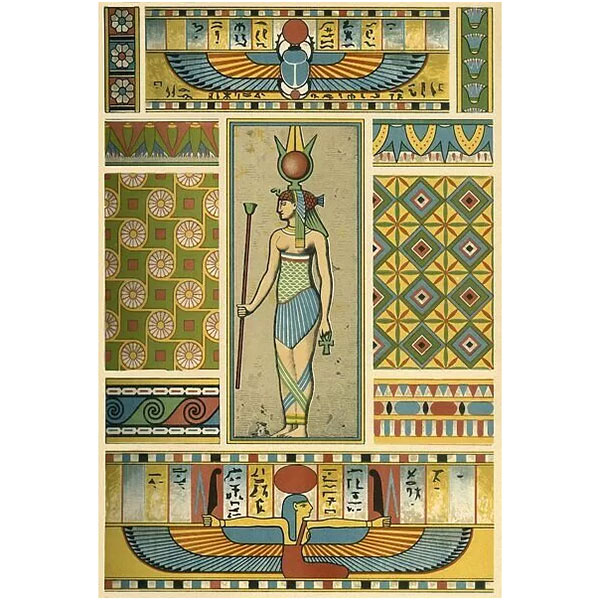

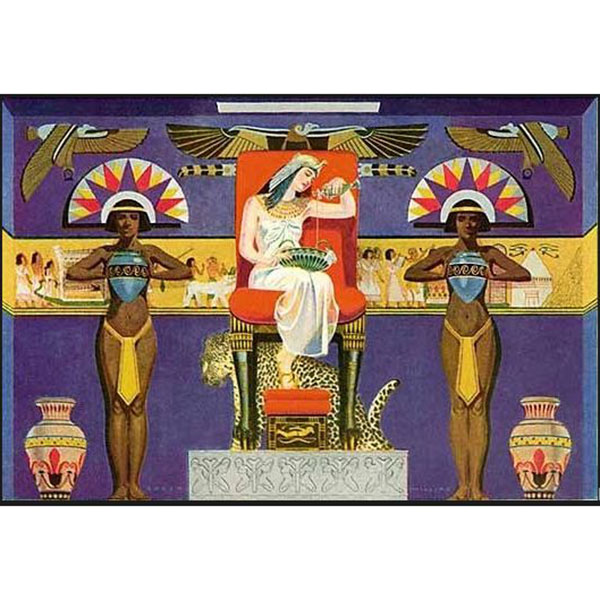

Isis Egyptian Design

Theda Bara as Cleopatra

Theda Bara Cleopatra Poster

Staffordshire Antony

Cleopatra detail

Staffordshire Cleopatra

Cleopatra aka Sleeping Ariadne Vatican

Cleopatra Engraving Vatican

Antony and Cleopatra M. Vandergucht

Wedgwood Rosso Antico Egyptian Club

Wedgwood Black Basalt Cleopatra

Wedgwood Egyptian Teapot

Antiquities Explained B. de Montfaucon

Wedgwood Jasper Canopic Jar

Wedgwood Carrara Cleopatra

Doulton Burslem, Cleopatra S. Wilson

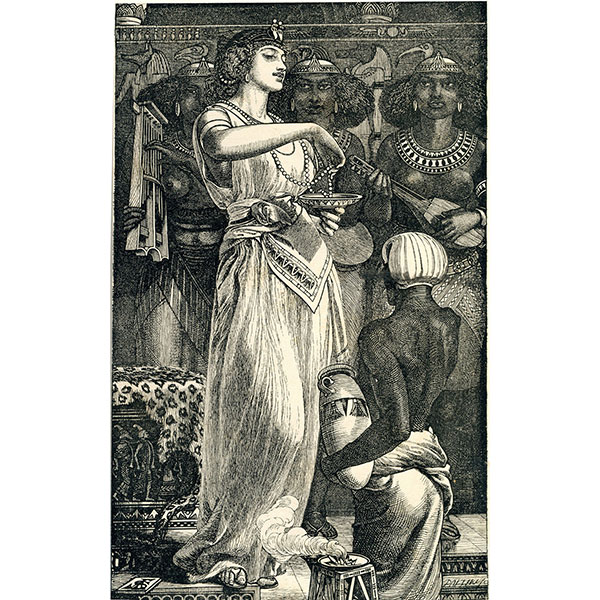

Cleopatra F. Sandys

Doulton Vellum Cleopatra C. J. Noke Detail

Doulton Vellum Cleopatra C. J. Noke

Egyptian Headdress

Lillie Langtry as Cleopatra

Lillie Langtry as Cleopatra

Sarah Bernhardt as Cleopatra

Sarah Bernhardt as Cleopatra

Theatre Magazine

Cleopatra’s Needle T.C. Crane

Cleopatra's Needle Victorian Embankment London

Erecting Cleopatra's Needle in New York

Victorian New Year Card

Rosenthal Salambo

Rosenthal Snake Charmer

Karl Ens Cleopatra

Herend Death of Cleopatra

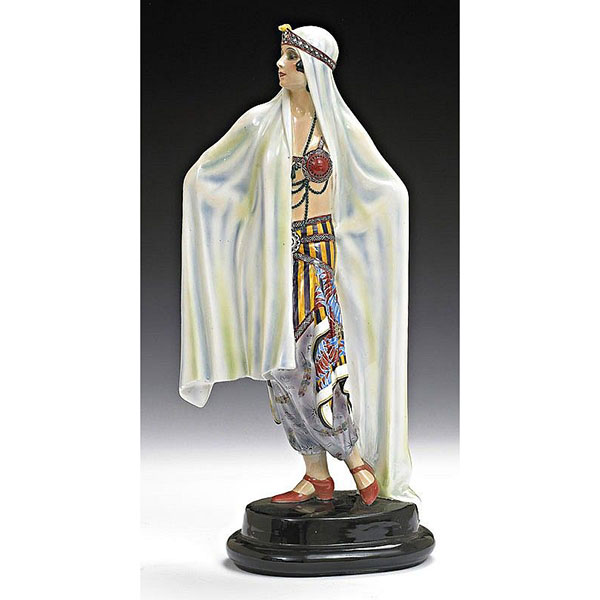

E & A Muller Veil Dancer

E & A Muller Egyptian Dancer

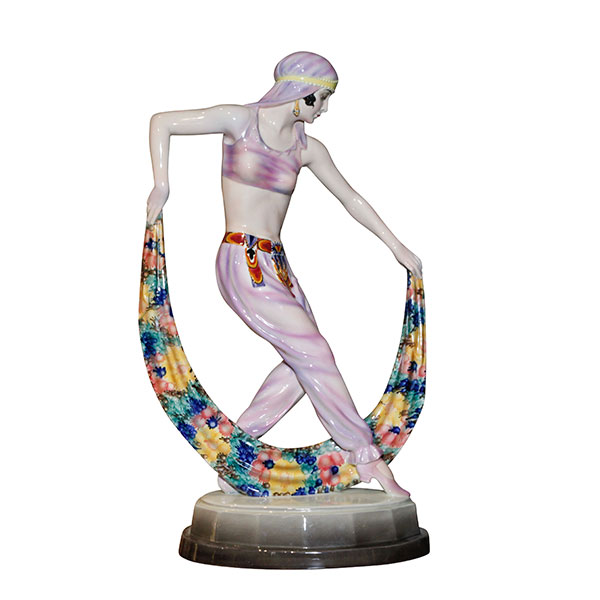

Goldscheider Arabian Dancer J. Lorenzl

Goldscheider Egyptian Dancer J. Lorenzl

Lore Wigand as Egyptian Dancer

Goldscheider Egyptian Dancer J. Lorenzl

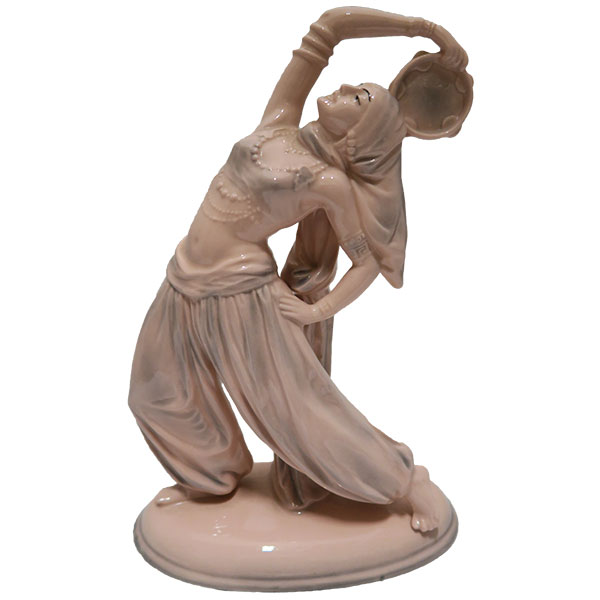

Goebel Sent Mahesa

Sitzendorf Sent Mahesa

Ballet Russes Cleopatra Costume by Sonia Delaunay

Ballet Russes Lubov Tchernicheva in Cleopatra costume by Sonia Delauney

Ida Rubinstein’s Cleopatra Ballet Russe Costume L. Bakst

Nina Payne Egyptian Dancer

Ruth St Denis Egyptian Dance

Sent Mahesa

Sent Mahesa

Palmolive Soap Advert

Theda Bara as Cleopatra

Theda Bara as Cleopatra

Theda Bara Cleopatra Poster