The forces of nature create glass. The essential ingredients of sand, soda ash, and lime are melted under intense fire with temperatures of 2400 degrees Fahrenheit. Glass can be formed when lightning hits sand and the resulting forms are known as fulgurites. Sea glass is formed over many years when salt-water weathers glass shards creating frosted effects. Human breath can be combined with molten glass, gravity and creative energy to blow spectacular art forms as evidenced by Dale Chihuly.

Dale Chihuly began blowing glass in 1965 and he says he is as infatuated with the material today as when he blew his first bubble. For Chihuly, the breath of life is the mysterious and magical force behind glass art. He wonders at the inventive genius who first thought of blowing a bubble of molten glass with a metal tube. He considers himself an explorer in glass searching for exciting new forms and colors that nobody has ever created before.

Throughout his 50-years as a glass artist, Chihuly has been deeply touched by nature. As a child, he was dazzled by the spectacular sunsets which he often watched with his mother, Viola, from the hilltop beside their home in Tacoma, Washington. His love of flowers is rooted in memories of his mother’s garden, blooming with azaleas and rhododendrons. On special holidays, they often visited the Seymour Conservatory in Wright Park to admire more exotic blooms.

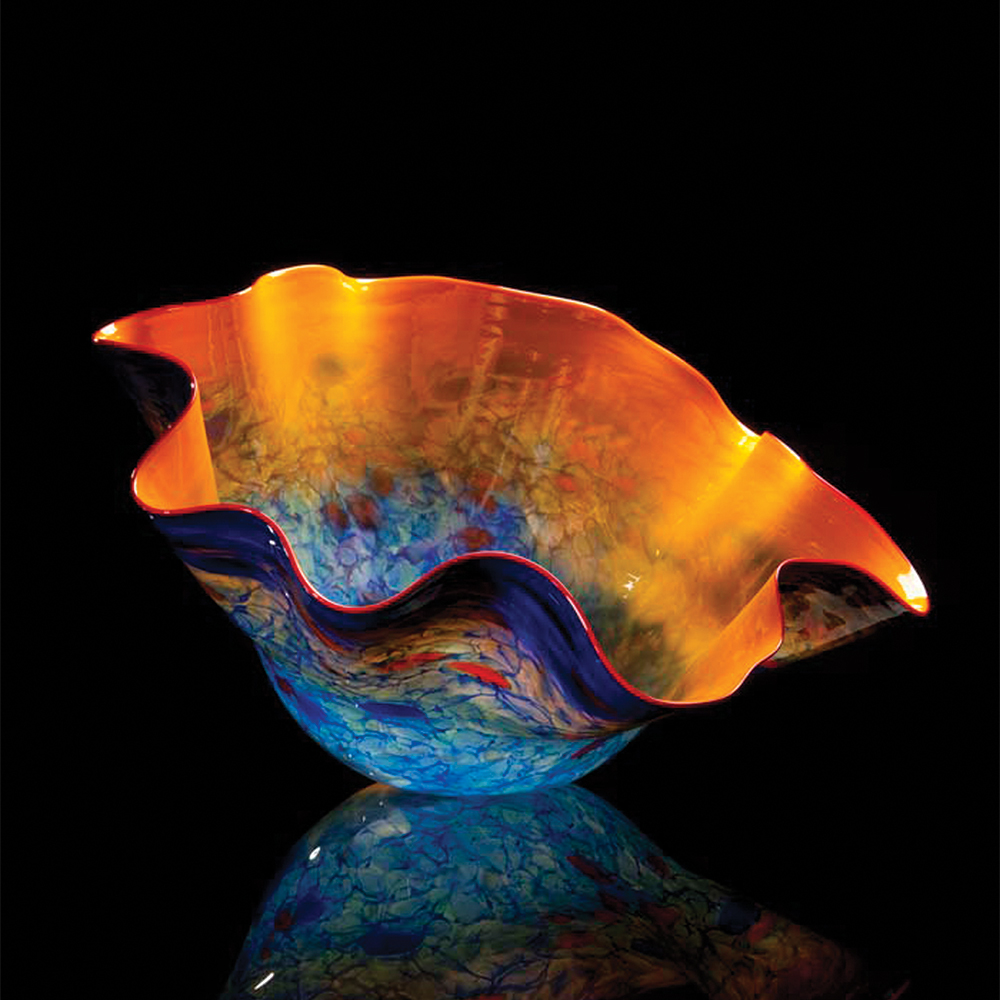

At WMODA, Chihuly’s rainbow Macchias seem to have burst into bloom from Viola’s vibrant flower beds. Macchia derives from the Italian word for a stain or spot but by the 17th century it had come to mean improvisational sketches that appear to be created by nature rather than a human hand. Chihuly often emphasizes this by displaying his Macchias on metal stands to resemble the stems of flowers. He also incorporates them into his garden installations where, surrounded by verdant foliage, they look like a garden in paradise.

In his garden installations, Chihuly was drawn to the synergy between glass conservatories and his art. The fact that the great 19th century glass palaces were clad in sheets of handblown glass filled him with awe. He sought them out during his travels around Europe and North America and began to visualize them as settings for his work. In 1995, while developing chandeliers for his Venetian project at the Waterford factory in Ireland, he was given the opportunity to embellish the gardens of Lismore Castle, the great hunting estate of the Dukes of Devonshire. His stunning Turquoise Frost chandelier for Lismore gardens is now in the private collection of Arthur Wiener in the Hamptons.

Chihuly also placed a cut crystal work in Lismore’s Vinery, a glasshouse designed by Sir Joseph Paxton, the architect of London’s Crystal Palace in 1851. Chihuly followed this with some work in the glass conservatory at Ireland’s National Botanic Garden at Glasnevin by Richard Turner, the same architect who designed the Palm House in the Royal Botanic Garden at Kew, London. Chihuly claims the Kew Palm House is his favorite conservatory in the world and he created epic installations there in 2005 and 2019.

Chihuly’s Garden Cycle also includes installations for some of the greatest gardens in the United States. In the last 20 years, he has moved from working within conservatories to displaying his work in various garden types, including tropical, temperate and desert. Chihuly’s dialogue with nature presents many challenges as the plants bloom, wilt and fade over the course of an exhibition. Seasonal plantings and colors need to be taken into consideration when planning the perfect integration of Chihuly’s glass with local flowers and foliage. His popular night viewings add a new dimension to the visitor’s experience.

Chihuly seeks not to copy nature but to emulate natural processes and sensory effects. He finds common ground between the nature of glass and nature itself. Chihuly has developed new works for each garden including many water features, such as the flock of Herons fishing in a pond of waterlilies at Fairchild Botanical Gardens in Florida.

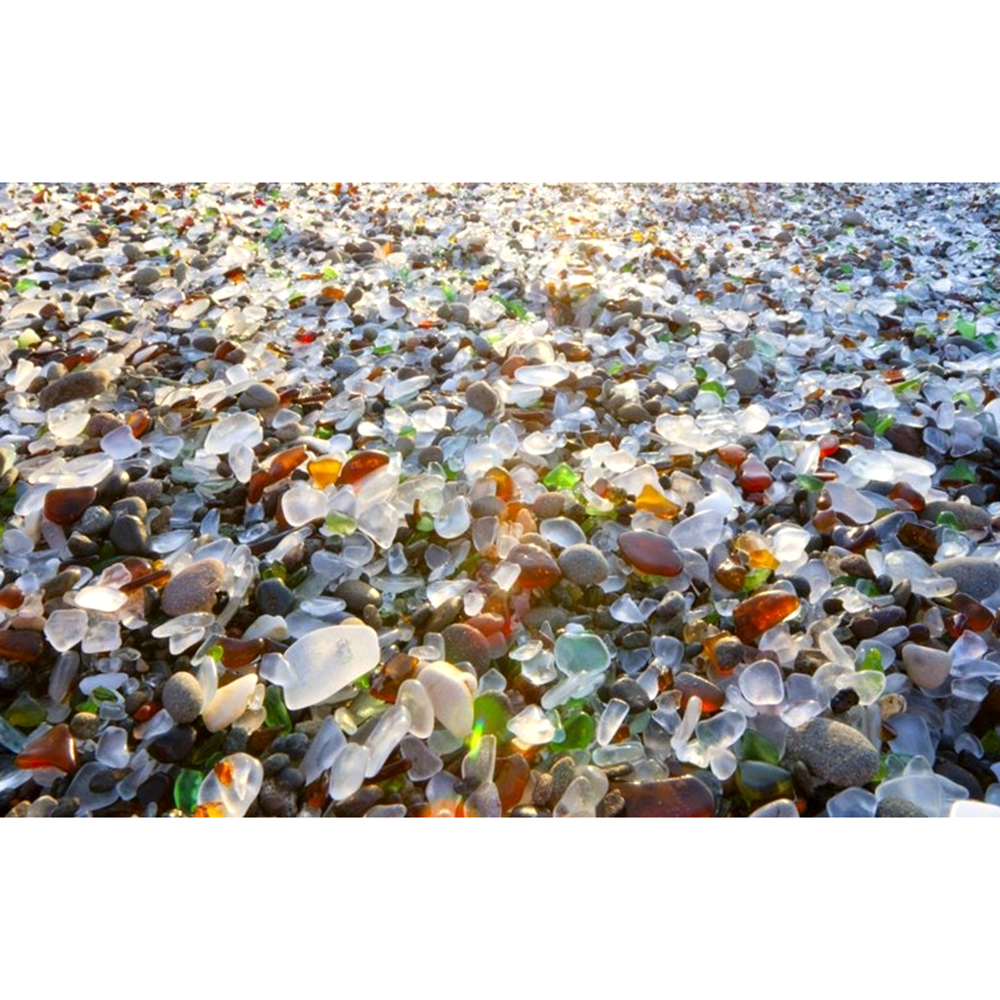

Growing up in the humid rainforest environment of the Pacific Northwest, Chihuly has deep ties to water in all its forms including snow, ice, waves, rain, fog and mist. He believes water is an important part of his creativity. Undaunted by rain, he has fond memories of family outings to the beaches of Puget Sound where he would search for sea glass and glass fishing floats blown in on the waves. He loves the legend of the shipwrecked Mediterranean sailors who accidentally created glass from a beach bonfire and some blocks of soda thousands of years ago. Being close to water is also evident in his “Boathouse” studio set on shores of Lake Union in Seattle.

Chihuly also expressed his love of nature and water in 1971 when co-founding the Pilchuck Glass School in the forested foothills of the Cascade Range, WA. The name was derived from the Chinook Indian words for red and water after the nearby Pilchuck River. Nicknamed “the Woodstock of Glass”, the early years at Pilchuck were part of the back to the earth movement of the hippy era. The first cabins were built by the students of environmentally friendly recycled materials and there was a communal gathering spot in the style of a tepee, reflecting Native American spiritualism and ecological responsibility.

Chihuly does not set out to study or copy marine life but some of his Seaforms are reminiscent of the radial patterns on shells and sea urchins. Other undulating forms evoke translucent jellyfish with floating tendrils. Often in the placement of his glass objects, he strives for the scattered effect created by a wave from the ocean which is different each time. His collaborations with the Murano maestro, Pino Signoretto, introduced more literal, sculptural interpretations of sea creatures from the lagoons of Venice.

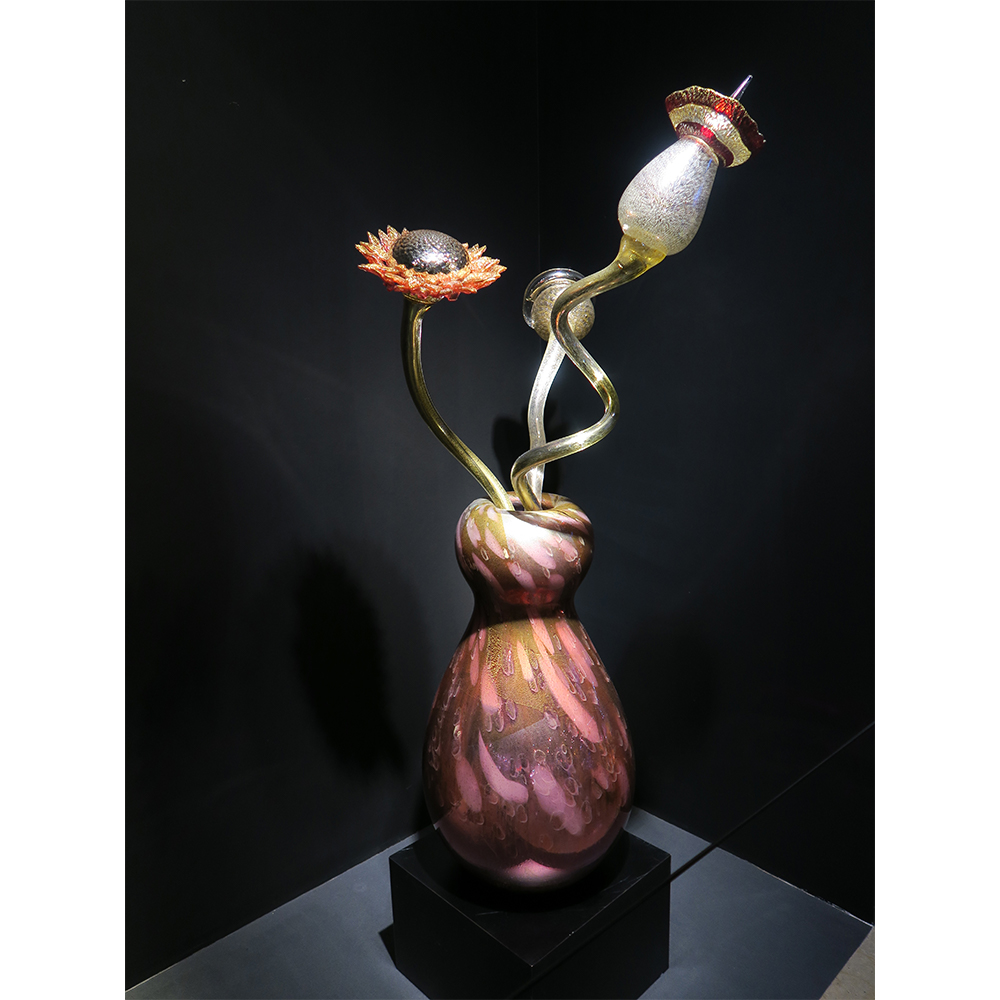

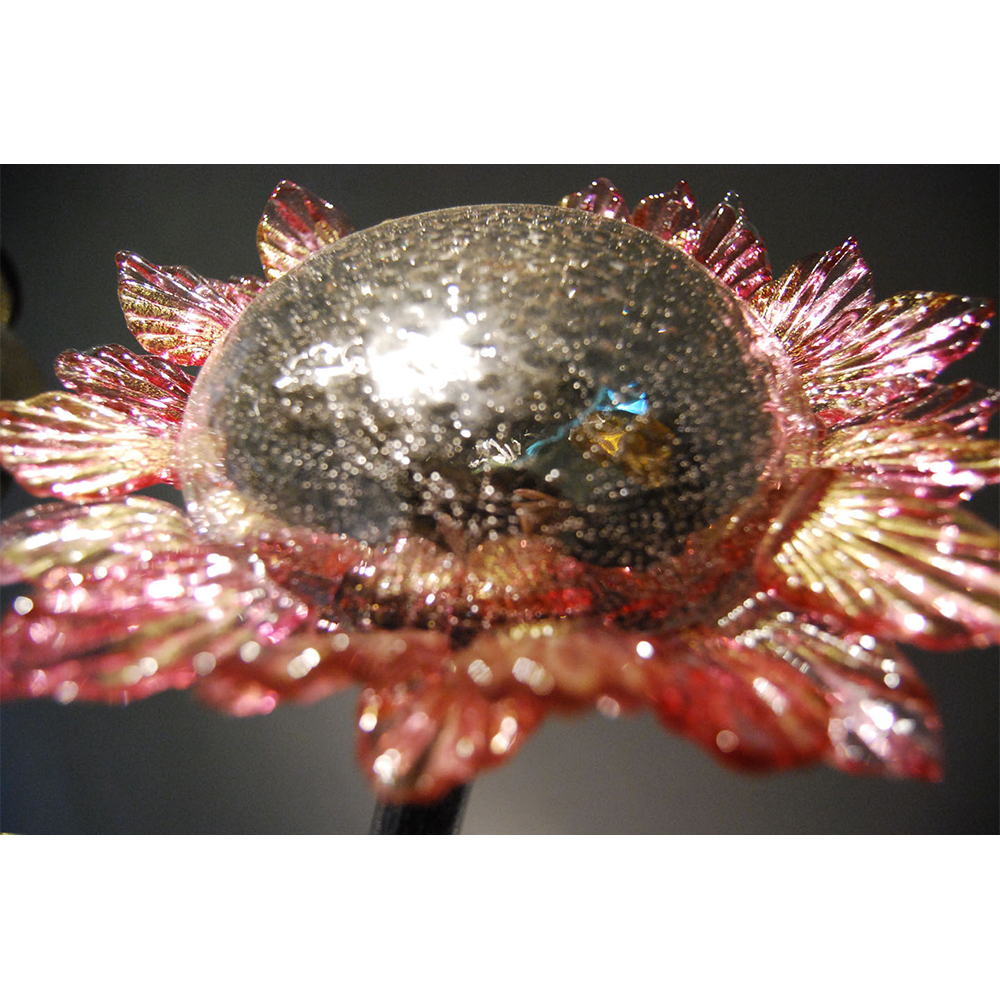

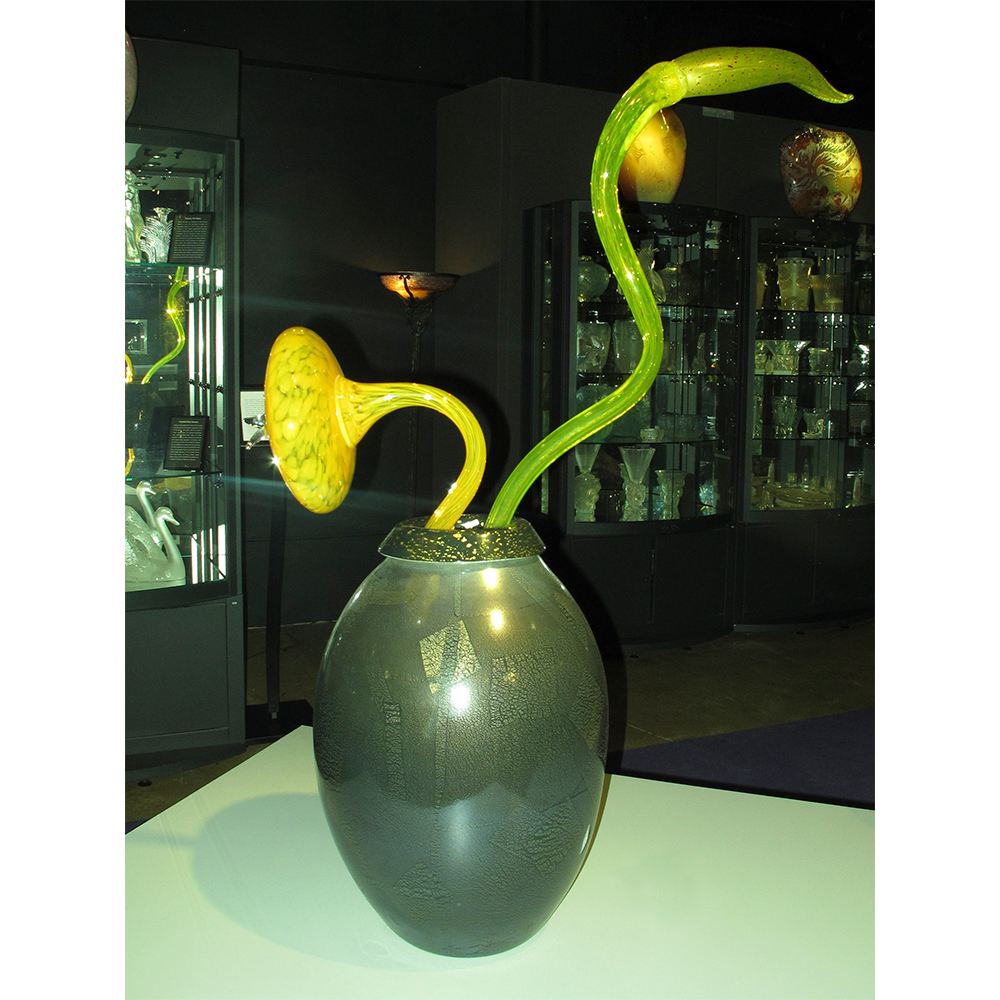

Working with the great Italian masters introduced Chihuly to traditional glass of the Art Deco era which he developed with Lino Tagliapietra into his Venetians series. In their hands, however, the vase is inundated with a profusion of exotic flowers, ferns, vines and flames. The organic evolution of his Venetian forms led to Chihuly’s Ikebana series, named after the Japanese art of flower arranging. His Ikebana forms have monumentalized the traditional vase of flowers. In this stylized aesthetic, Chihuly’s massive vases are arranged with stems, leaves and blossoms, sometimes reaching over six feet tall. They bring to mind his mother’s abundant flower garden and also Chihuly’s love of Van Gogh’s sunflowers, which was the subject of his first art history paper in college.

See a fabulous collection of Chihuly’s natural forms in the Art on Fire exhibition at WMODA.

Read more...

“My work to this day revolves around a simple set of circumstances: fire, molten glass, human breath, spontaneity, centrifugal force, gravity.”

-Dale Chihuly

Chihuly Macchia Forest at WMODA

Fulgurite glass forms when lightening strikes sand

Sea glass

Sea glass on a beach

Chihuly Macchia Forest at WMODA

Chihuly Macchia

Chihuly Macchia

“I often show the Macchia in what we call a ‘Macchia Forest’, where a half dozen, even fifty of them can be together on different sized stands.”

Chihuly Turquoise Frost chandelier at Lismore

Chihuly Turquoise Frost chandelier in the Hamptons

Chihuly at Kew

Chihuly at Kew

Chihuly at Kew

Chihuly at Fairchild Gardens

Chihuly at Kew

“Over time I developed the most organic natural way of working with glass, using the least amount of tools that I could. The glass looks as if it comes from nature.”

Chihuly at the Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, 2014

Chihuly at the Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, 2014

Chihuly at the Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, 2014

“Water is the one thing that I can assure you is a major influence on my work and my life and everything I do...If I don’t feel good or I don’t feel creative, if I can get near the water something will start to happen.”

Chihuly Blue Seaform

Chihuly Blue Seaform detail

Chihuly White Seaform

Jellyfish

Jellyfish

Chihuly Seaform Set

Shells

Chihuly Seaform Set

Chihuly Seaform Vessel

Sea Urchin

“Glass itself is so much like water. If you let it go on its own, it almost ends up looking like something that came from the sea.”

Chihuly Venetian

Chihuly Piccolo Venetian

Chihuly Opera Blue Piccolo Venetian

“I like things to feel that they sort of happened by nature and not been put there by man”

Chihuly Pink Ikebana

Chihuly Rose Ikebana detail

Chihuly Ikebana Flower detail

Chihuly Ikebana Stem detail

Chihuly Ikebana in the Hamptons

Chihuly Ikebana

Chihuly Blue Ikebana

Chihuly Yellow Ikebana