By Louise Irvine

Statuary porcelain became a phenomenal success in the Victorian art world thanks to the popularity of lotteries. The first art unions in Britain were formed in the 1830s to promote the fine arts. Members paid a subscription and participated in an annual lottery to win contemporary works by British artists and designers. Popular prizes included porcelain sculptures made in imitation of marble by the Copeland and Minton factories in Stoke-on-Trent.

William Taylor Copeland and Herbert Minton both claimed to be the original inventor of this successful new ceramic body. Copeland marketed it as “Statuary Porcelain” and Minton named it “Parian” because it resembled the fine marble quarried on the Isle of Paros in Greece. Wedgwood introduced “Carrara” named after the marble from Northern Italy. Marble was considered elegant and opulent by the Victorians and the marble-like porcelain with its exquisite sheen was a novel attraction.

Distinguished sculptors of the period believed strongly in the artistic merit of Parian as a medium and recognized its commercial potential. The Royal Academician, John Gibson, made determined efforts to establish the new material describing it as the “next best thing to marble.” He met with officials from the Art Union of London and in 1846 they commissioned Copeland to produce 50 copies of his figure of Narcissus which had been awarded a diploma of honor at the Royal Academy. A “reduced copy” was eventually permitted by the Academy although access to make a clay mold of the marble original was refused. At the last minute, it was considered judicious to add a fig leaf to the undraped figure but despite all the production difficulties, the lottery prize was an immediate success. The following year, the Art Union paid 100 guineas to the sculptor John Foley for a reduced copy of his statue of Innocence.

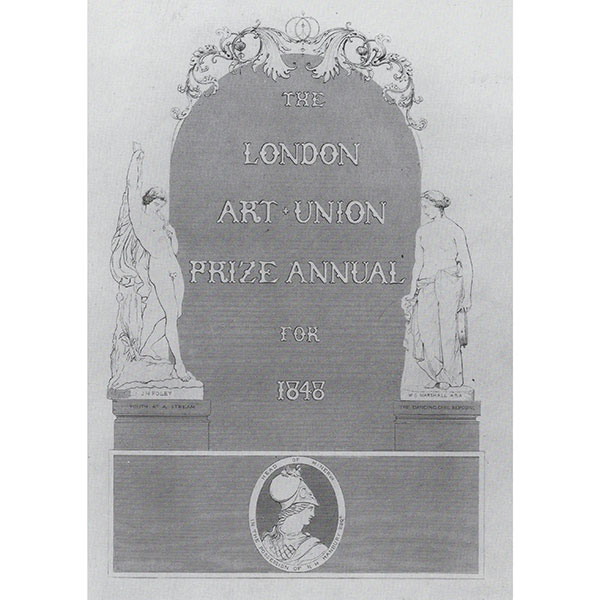

Before long, art unions throughout the country were seeking permission from leading sculptors to reproduce their existing carved works in marble or to model new designs for production in Parian. The Art Union of London became the largest and the most influential in promoting the idea of art for all and the improvement of public taste. Patronage for living artists was expanded and people from all walks of life became engaged in the cultural life of the times. For a guinea subscription, members received an engraving with the same nominal value and the chance of winning a prize in the annual ballot. Membership of the art unions thrived as the element of chance added to the frisson of art appreciation.

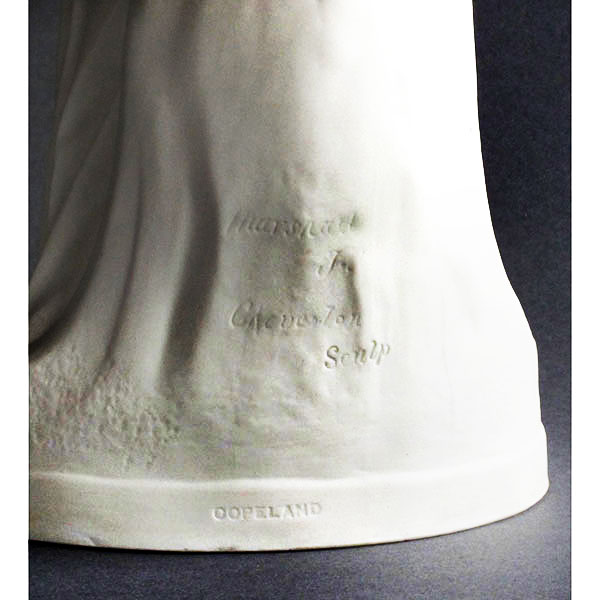

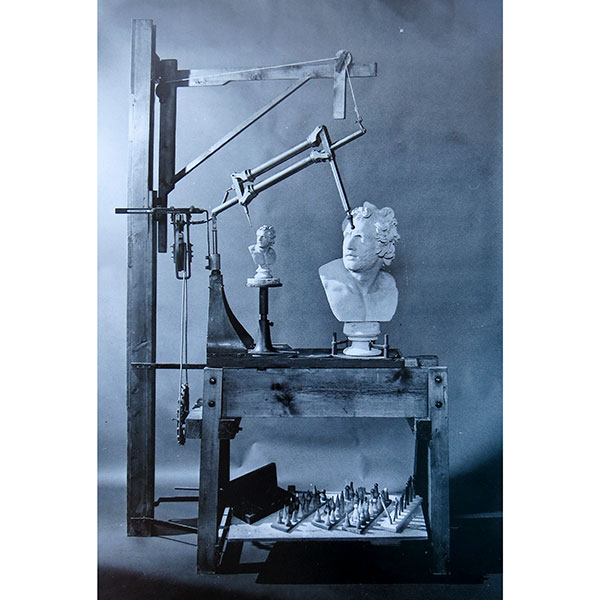

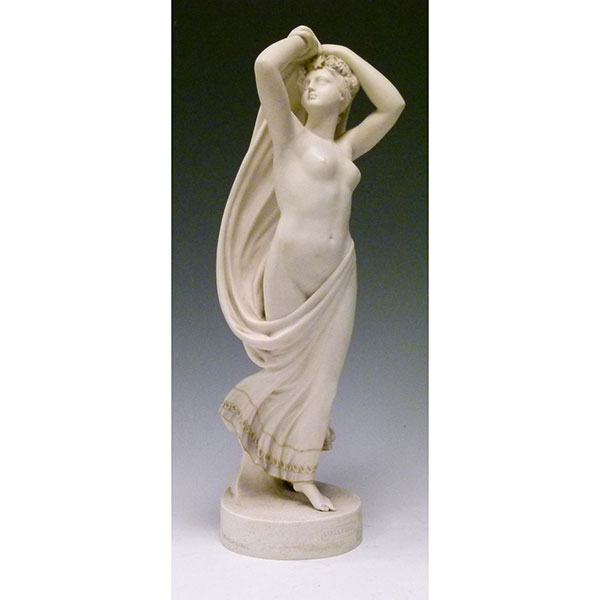

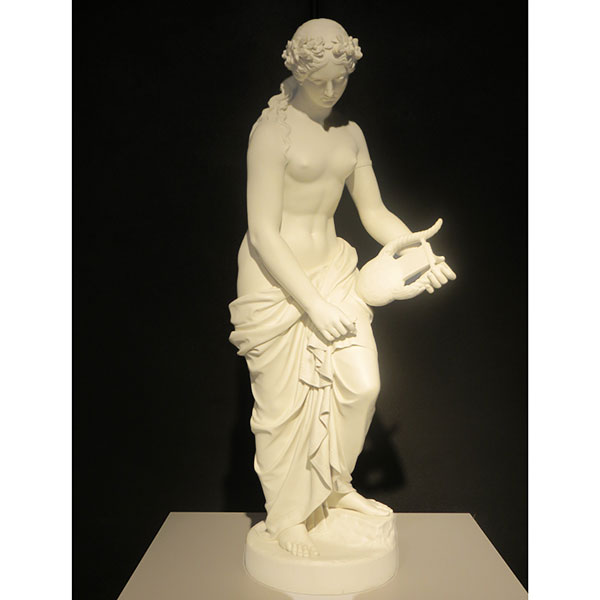

Original marble figures or busts were scaled down by Benjamin Cheverton’s reducing machine so that molds could be made for mass production in porcelain. Cheverton’s name is inscribed on The Dancing Girl Reposing along with the sculptor William Calder Marshall who was paid a premium price of £500 for a reduced version of his marble by the Art Union of London. 235 copies of the 18 inch statue were ordered from the Copeland factory between 1848 and 1857. Minton produced 150 figures of Solitude by John Lawlor for Art Union of London lotteries in between 1852 and 1854. A bust of HRH the Princess of Wales was a popular prize in 1863 with 300 ordered from Copeland while their most popular figure was the cute Go to Sleep by Joseph Durham with 425 made for annual lotteries in 1863, 1864 and 1865.

Queen Victoria was an early subscriber to the Crystal Palace Art Union which most successfully capitalized on the public’s enthusiasm for Parian Ware. The publicity generated by the art unions also encouraged purchases of Parian figures and busts direct from the manufacturers at exhibitions. Only the more affluent could afford them as the typical cost was 3 guineas for a bust or figure when the weekly wage for an average Victorian family was a pound or so.

An attempt to increase subscriptions in provincial art unions led to one shilling lotteries but they were condemned for their speculative nature by the artists and the government. Art unions went into a decline in the late 1860s as potential subscribers were spending their money on sporting events and other amusements including visiting the new museums and public libraries. The popularity of Parian ware also waned as colorful Majolica ware captivated the Victorian public.

Read more about Parian Ware at WMODA

Copeland Narcissus J. Gibson

Copeland Dancing Girl Reposing W.C. Marshall

Art Union of London Inscription

Copeland Dancing Girl Reposing Inscriptions

Art Union of London Annual 1848

Cheverton Reducing Machine

Copeland Daphne M. Wood

Copeland L'Allegro E. H. Baily

Copeland HRH Princess Alexandra M. Thornycroft

Copeland Enid F. M. Miller

Copeland Sappho W. Theed

Go to Sleep Engraving Art Journal 1864

Copeland Go to Sleep J. Durham

Copeland Little Red Riding Hood T. Woolner

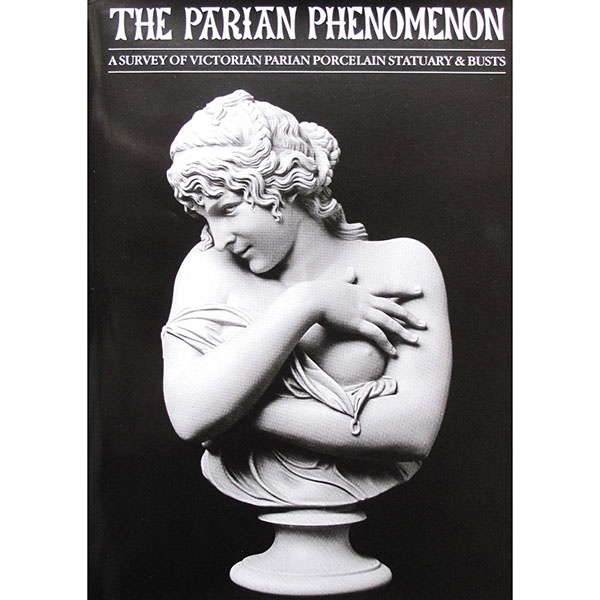

Parian Phenomenon Book

Parian Exhibition at WMODA