WMODA was honored to receive gifts from the Starr collection of English ceramics, which was auctioned at Sotheby’s last year. The sale entitled Wedgwood and Beyond featured 33 superb lots of Minton’s pâte-sur-pâte designs and Solon’s Tug of War is now on display in our Fantastique exhibit.

Minton Tug-of-War by Solon

Minton Pâte-sur-Pâte

The Minton factory excelled in pâte-sur-pâte decoration, a French term meaning paste on paste. Successive layers of white liquid clay, known as slip, are applied with a brush to an unfired and unglazed colored body to create a translucent relief image. Marc-Louis Solon (1835-1913) was the chief exponent of this technique at Minton.

Solon began his career as a ceramic designer at the Sèvres factory, where he worked on the pâte-sur-pâte process that they were developing in the mid-19th century. The Franco-Prussian war of 1870 forced Solon to flee France and seek refuge in Stoke-on-Trent, where several of his compatriots were working, including Leon Arnoux, Minton’s art director. Arnoux was responsible for Minton’s display at the Great Exhibition of 1851 where his new majolica glazes were enthusiastically received. Arnoux’s daughter Maria married Solon not long after he arrived in the Potteries.

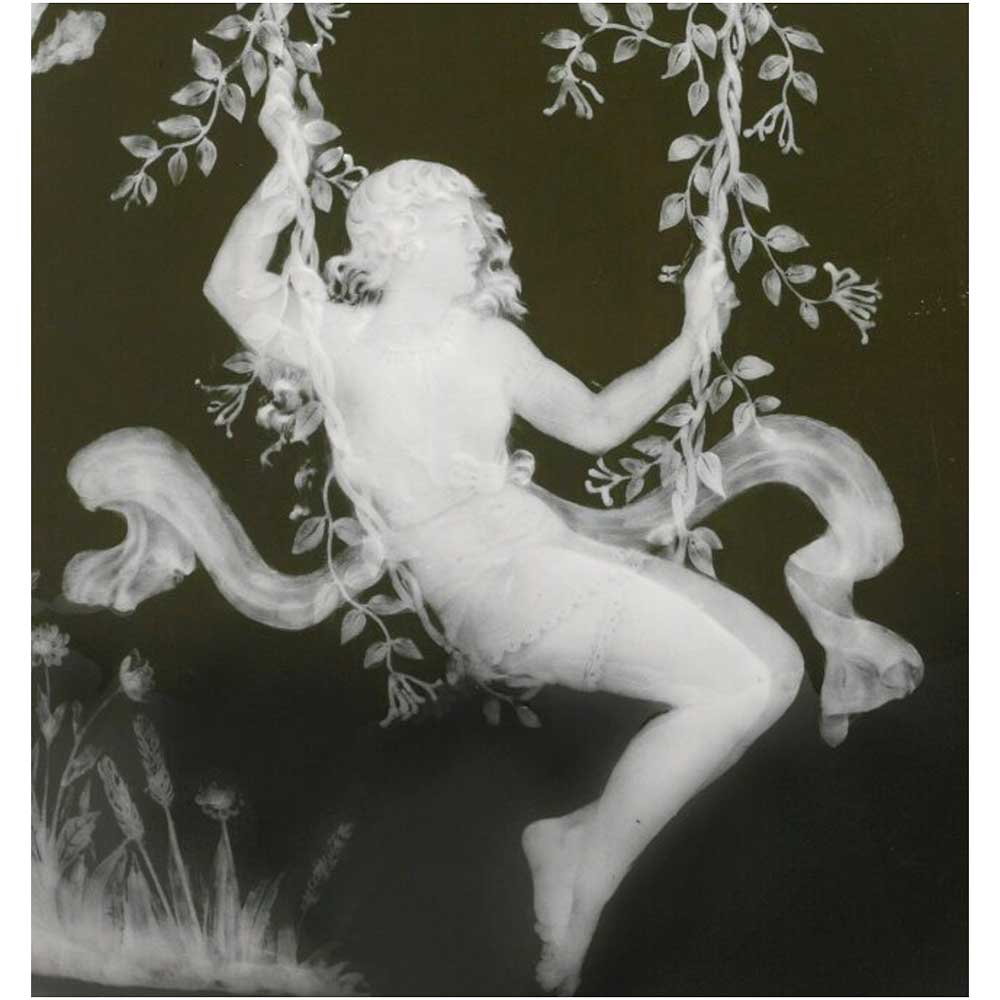

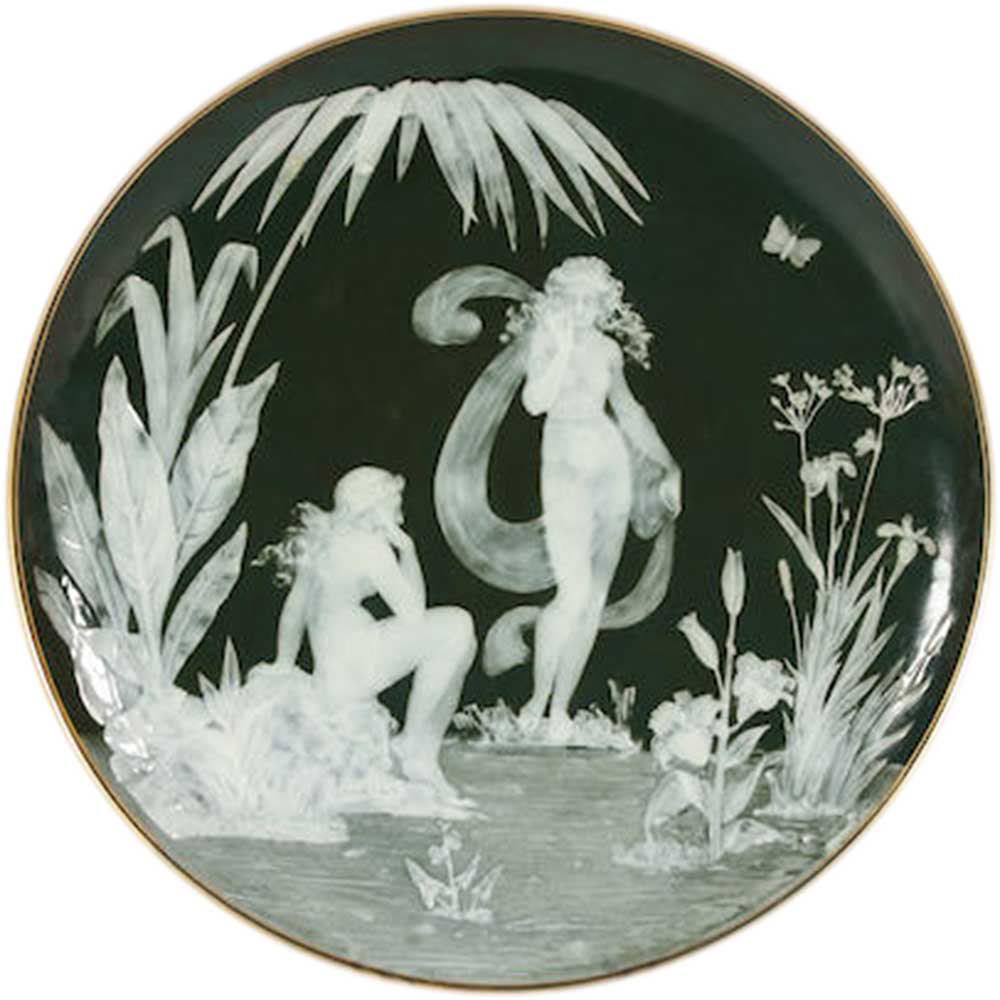

Solon began his pâte-sur-pâte trials at Minton on their parian body, which had been so successful for statuary. It proved to be very suitable for the wide range of colored bodies which Solon employed, including peacock blue, rose pink, olive, bronze-green and browns. The strong ground colors contrasted beautifully with the delicate white slip decoration. The pâte-sur-pâte process requires both painting and modeling skills to secure a crisp, brilliant finish when the piece is fired and coated in a transparent glaze. The success of Solon’s pâte-sur-pâte designs depended on the subtle translucency he achieved, whether it be a maiden’s diaphanous draperies or cupid’s feathered wings.

Inspiration was drawn from classical sources and French 18th century designs but Solon brought his own charming sense of humor to his love stories which unfolded around his pâte-sur-pâte vases. He delighted in portraying cherubs in a variety of sporting activities, including our recently acquired Tug-of-War scene. Solon spent all his time at Minton concentrating on the pâte-sur-pâte process. Typically, it took him around three weeks to create a pair of vases although some of his masterpieces took many months to complete. His pâte-sur-pâte designs were highly regarded in his lifetime. At the peak of his success in 1897, an exhibition of his work was held in London to celebrate the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria.

In addition to his work in the Minton studio, Solon acquired slabs from the factory which he decorated in his own time so that he could experiment with pictorial compositions on a flat surface. Many of these were bought by Minton and incorporated into furniture or framed as wall art. He continued working at home when he left Minton in 1904 until his death in 1913. In his retirement, he was able to devote more time to collecting ceramics and books on the subject. During his lifetime, he amassed more than 4,000 books in many languages and compiled a bibliography entitled The Ceramic Literature.

Solon was always very generous with his talents and enjoyed explaining the pâte-sur-pâte process to visitors. He also trained many apprentices, some of whom continued the technique at Minton and elsewhere. Alboin Birks was responsible for Minton’s pâte-sur-pâte studio until the 1930s. WMODA has an exquisite vase and cover by Birks from 1918, which features Diana, the huntress asleep in the woods with cupid watching over her.

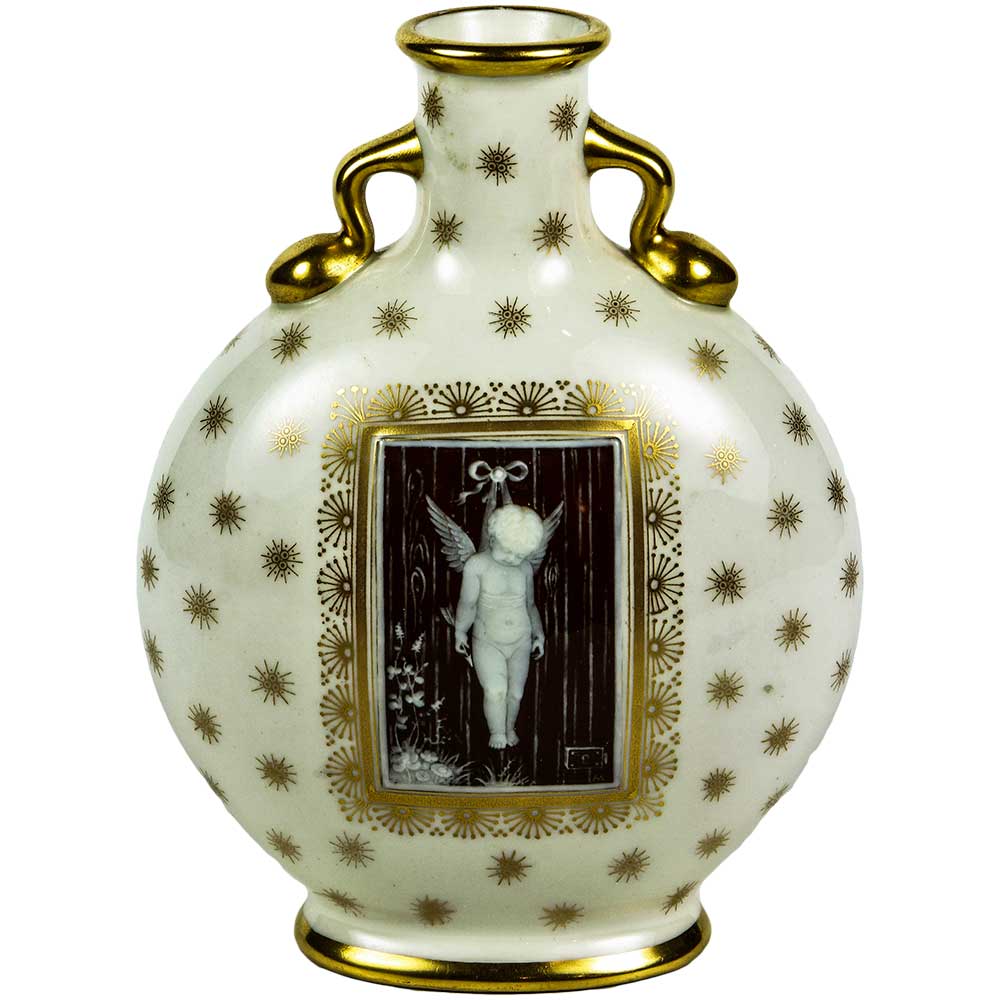

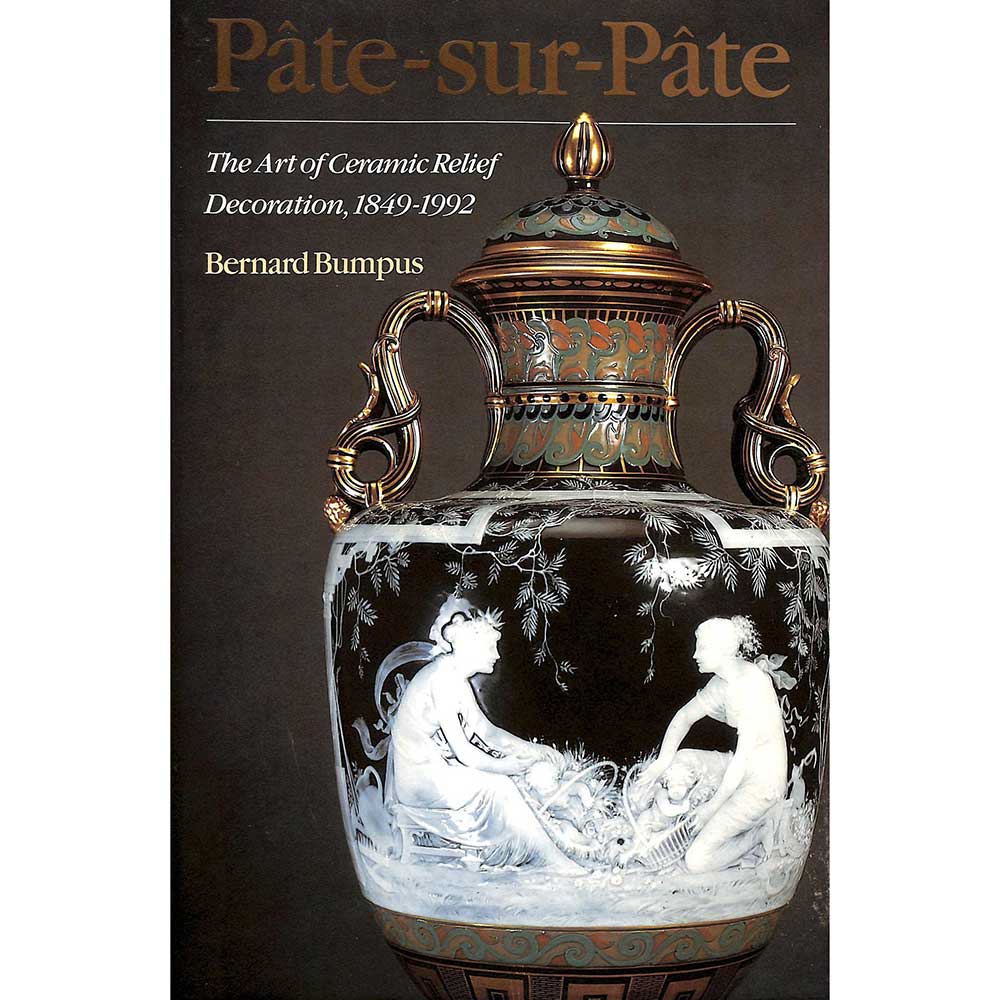

Henry Hollins was one of Solon’s first apprentices at Minton in 1873 and he was responsible for the 1884 moon flask depicting Psyche now at WMODA. One of Solon’s most gifted students was Arthur Morgan, who produced the Minton moon flask depicting Cupid Punished c.1880 in our Fantastique exhibit. This piece was formerly in the collection of Bernard Bumpus, the erudite ceramic historian who studied pâte-sur-pâte designs produced by different manufacturers. In preparation for his book on the subject, he spent many hours in the Doulton archives and helped us shed more light on the migration of Minton artists.

Doulton Pâte-sur-Pâte

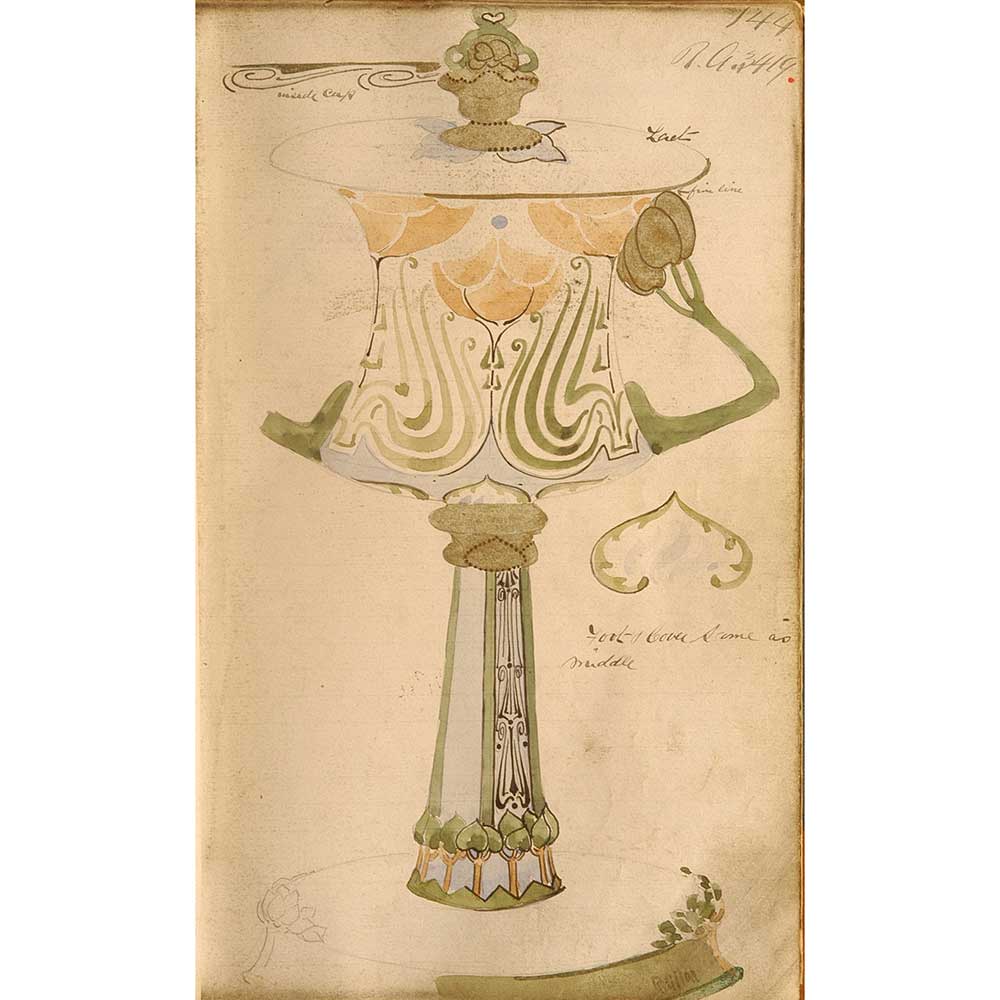

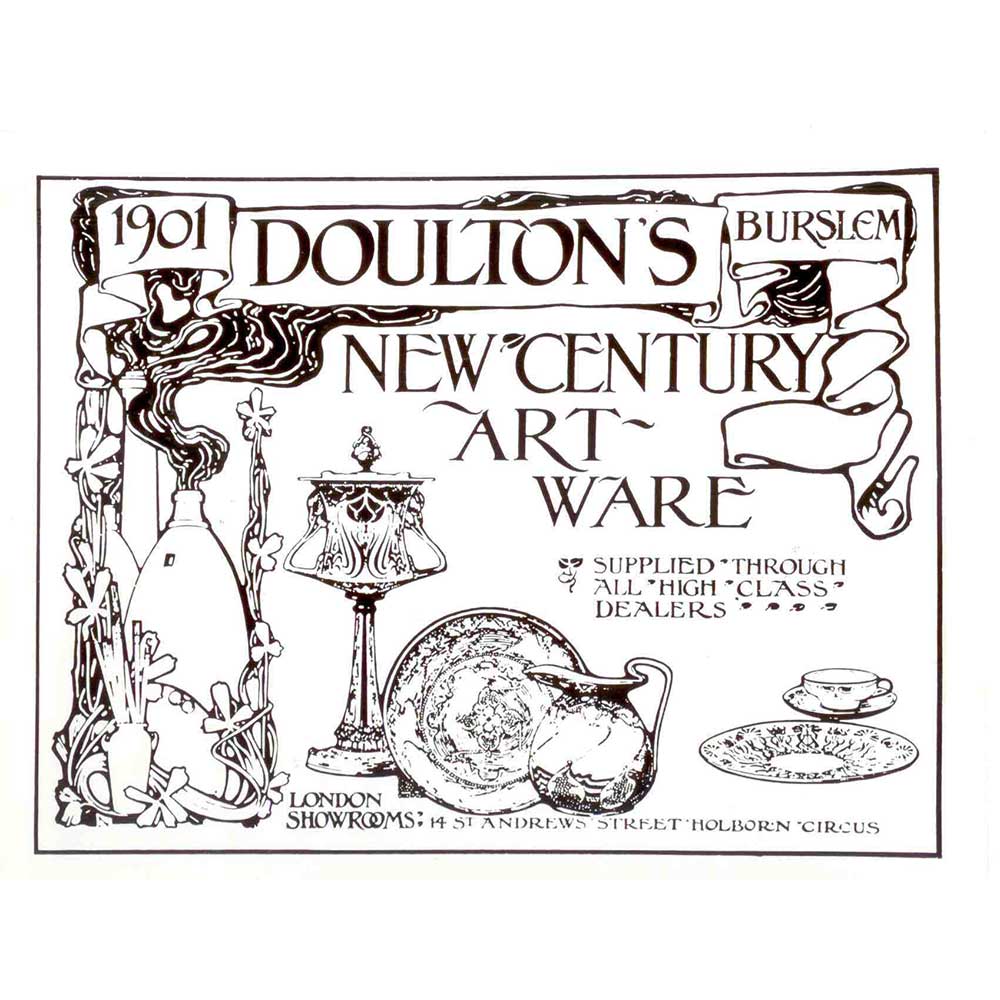

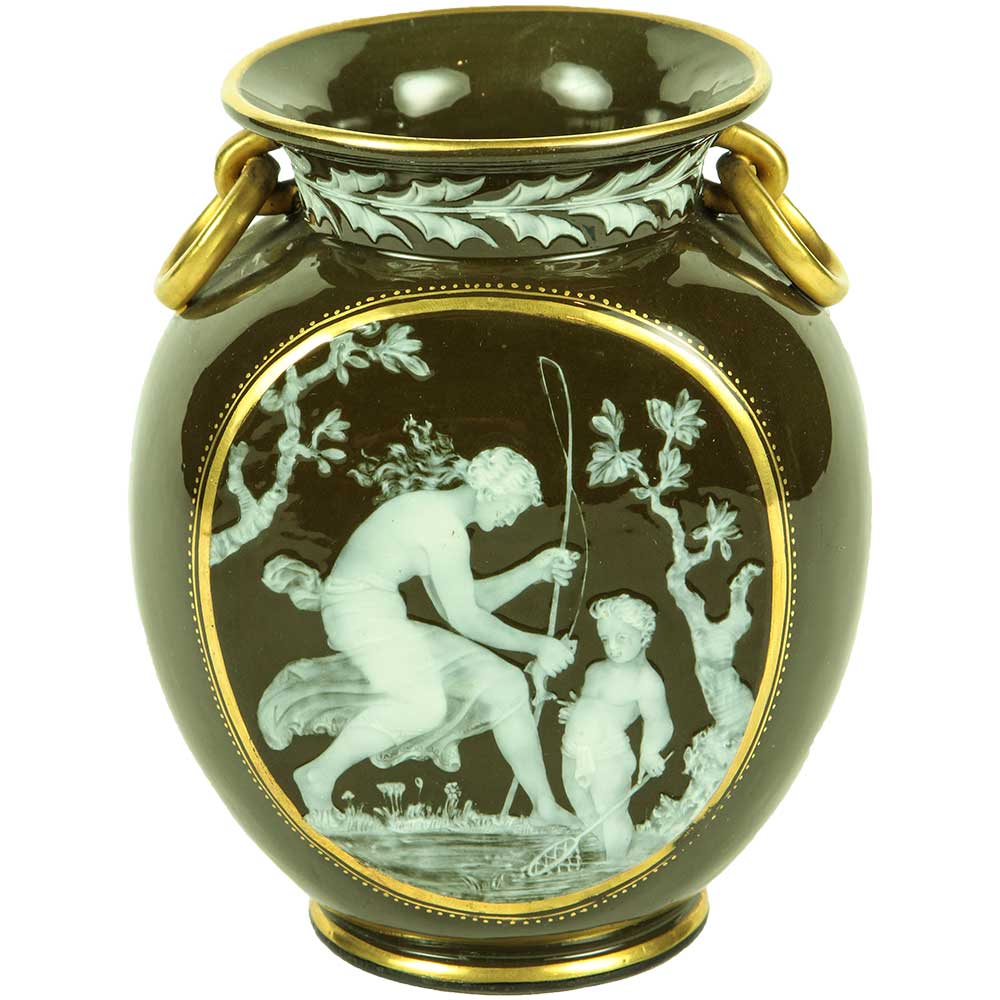

Arthur Morgan worked on pâte-sur-pâte designs for Doulton’s Burslem Studio, including a richly gilded three-handled tyg depicting Cupid on display in the Fantastique exhibition. The Doulton studio also benefitted from the expertise of William Hodkinson, who learned some of the pâte-sur-pâte techniques while apprenticed at Minton under Léon Arnoux. He worked with Thomas Rice, another former Minton artist, on some exquisite Doulton pâte-sur-pâte vases during the 1890s. Later, he helped art director Charles Noke develop the Lactolian Wares using their parian type body, which was originally developed for Noke’s Vellum figures. Lactolian Ware, from the Latin for milky, was launched at the Paris Exhibition of 1900. Production was very limited as it was time-consuming and expensive to produce and was discontinued after just a few years for economic reasons.

Doulton’s Lambeth studio in London also developed a type of pâte-sur-pâte decoration on stoneware but the effects are quite different from the porcelain bodies used in Stoke-on-Trent. As John Sparkes, head of the Lambeth School of Art, pointed out in 1880, “ To paint with the earthy pigment requires great delicacy of hand and accuracy….it required much practice and unerring certainty in planting the material on the ware firmly and in the right place.” The most talented artists working with this stoneware technique at Lambeth were Florence Barlow, Edith Lupton and Harry Barnard, who went on to perfect the slip-trailing tube-lining technique used by Moorcroft.

George Jones Pâte-sur-Pâte

George Jones was another Minton apprentice, who branched out on his own. He became a traveling salesman and china merchant before setting up his own pottery in 1862. Jones focused initially on making majolica wares, which were at the peak of their popularity at the time, and he employed more than 500 skilled workers in the late 19th century. George Jones also produced pâte-sur-pâte designs and there are some striking examples decorated by Frederick E. E. Schenck c.1885 at WMODA. Schenck went on to become a successful architectural sculptor in London.

Minton Tug-of-War by Solon details

Minton Covered Vase by A. Birks

Minton Psyche by H. Hollins

Minton Cupid Punished by A. Morgan

Pâte-sur-Pâte by B. Bumpus

Doulton Burslem Cupid Tyg by A. Morgan

Doulton Burslem Cupid Tyg by A. Morgan side two

Royal Doulton Lactolian Ware

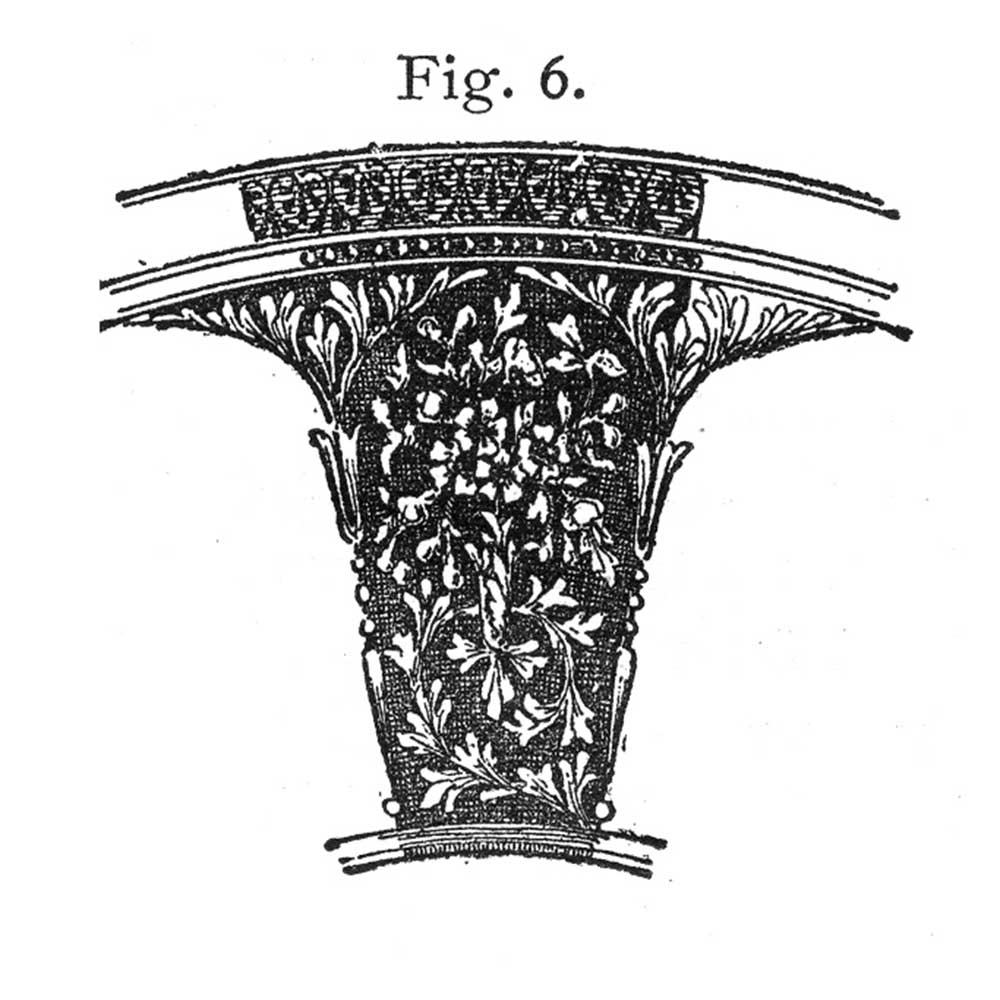

Royal Doulton Lactolian Ware design

Royal Doulton Advertisement for New Century Art Ware, including Lactolian Ware, 1901

Doulton Burslem Pâte-sur-Pâte

Doulton Lambeth Pâte-sur-Pâte by F. Barlow detail

Doulton Lambeth Pâte-sur-Pâte by F. Barlow detail

Doulton Lambeth Pâte-sur-Pâte design

George Jones Pâte-sur-Pâte Vase by F.E.E. Schenck

George Jones Pâte-sur-Pâte Vases by F.E.E. Schenck

George Jones Pâte-sur-Pâte detail

George Jones Pâte-sur-Pâte Plaque by F.E.E. Schenck