Self-Guided Tour

We have highlighted some of the key exhibits in the museum to explore in more depth. Scroll down to begin your tour. You can listen to the commentary by Louise Irvine, our Executive Director and Curator, or you can read a transcript. For the enjoyment of everyone, please keep the volume low or, even better, wear headphones.

Introduction

Welcome to the Wiener Museum of Decorative Arts, where we celebrate the Fired Arts of ceramics and glass. Our vast collection spans centuries and continents, and our galleries highlight major design trends, such as Art Nouveau and Art Deco. Our Studio Collection and Museum Shop feature artists working in our community today.

WMODA was founded in 2014 by Arthur Wiener, a passionate collector of ceramic art and studio glass. He has been donating his vast collection to our not-for-profit museum so that a wide audience can share the inspirational power of the Fired Arts.

Let us fire your imagination with some of the highlights in this audio tour….

Just a few things to mention before we begin. As a courtesy to our other guests, please wear headphones or set the volume low during the audio tour.

Please do not touch the exhibits. You are welcome to take photographs for your personal use and we encourage you to share your visit on our social media pages.

Restrooms and gift shops are located on both floors.

1 – Maharaja Vase

This colossal vase is the largest piece in our collection and the largest piece ever made by Doulton’s Lambeth Pottery in London. It stands over six feet tall and weighs more than 500 pounds. It was one of the most challenging pieces to move from our previous location, as it didn’t fit through the interior door! We had to wheel it around the block in the rain and bring it through the double doors at the entrance to the museum.

The vase was acquired in 1893 by the Maharaja of Baroda, an Indian Prince who was the sixth richest man in the world during the Victorian era. He loved England and traveled to London regularly to shop for his magnificent Lakshmi Vilas Palace, the largest private residence ever built at that time.

On a visit to Doulton’s Lambeth Pottery, the Maharaja commissioned several large Faience vases and jardinières, which can still be seen in his Indian palace today. The current Maharani of Baroda was in touch with the museum a few years ago for information about the pieces in her collection.

Miss Florence Lewis decorated this spectacular vase with a profusion of tropical flowers. Miss Lewis was the supervisor of Doulton’s Lambeth Faience painting department, mainly staffed by young women. She decorated a twin vase, which was the crowning glory of the Chicago World Columbian Exposition in 1893 and is now in the Museum of Science and Industry. On the second floor, you can see another monumental Faience vase painted by Florence Lewis for the Maharaja of Baroda.

2 – Art on Fire – Dale Chihuly

This spectacular glass wall was made by Dale Chihuly, the most influential glass artist in America. Throughout his career, Chihuly has pushed the traditional boundaries of glass to create incredible installations in public buildings and botanical gardens. He allows natural forces and gravity to let molten glass find its form and has experimented on a massive scale with dynamic color, light and translucency.

Many of Chihuly’s dramatic wall and ceiling installations incorporate his Persian forms with their luminous jewel tones and spiraling body wraps. Our wall was made in 1996 for the Chihuly Room at Wolfgang Puck’s groundbreaking Postrio Restaurant in San Francisco. His Persian rondels resemble giant wall flowers on a garden trellis.

The Postrio Restaurant also featured two Chihuly paintings which are displayed in this gallery. His works on paper are painted spontaneously with a broom on the floor. They are important forms of creative expression and a way to communicate the concepts he wants to explore in glass to his assistants.

WMODA is also proud to present glass art by many of Chihuly’s mentors, collaborators and students, including Lino Tagliapietra, Pino Signoretto, William Morris and Toots Zynsky. You’ll see their works throughout our Hot Glass Gallery.

3 – Chihuly’s Garden of Glass

Chihuly was born in Tacoma, Washington, in 1941. He first learned to melt and fuse glass in 1961 and four years later discovered glassblowing which became his lifelong passion. He enrolled in the first American glass program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and his studies continued at the Rhode Island School of Design, where he later taught. After receiving a Fulbright Fellowship in 1968, Chihuly became the first American glassblower to apprentice with the famed Murano masters. He brought many of the techniques he learned in Venice back to the USA; foremost among these was the collaborative approach to team glass blowing.

Accidents in the late 1970s left Chihuly with a blind eye and an injured shoulder. He could no longer blow glass himself, so he directed his gaffers and glass blowers more like a choreographer than a dancer.

Chihuly’s love of color can be seen in his Macchia series, which came about after he woke up one morning in 1981 wanting to use all 300 colors in his hot shop. They give the impression of a riotous garden in full bloom with his giant Ikebana vessels, named after the Japanese art of flower arranging. Chihuly’s love of nature and flowers is rooted in happy childhood memories of his mother’s garden.

WMODA was invited to create a Chihuly Macchia garden at the National Building Museum in Washington, DC, when the Smithsonian Institution honored Chihuly in 2016.

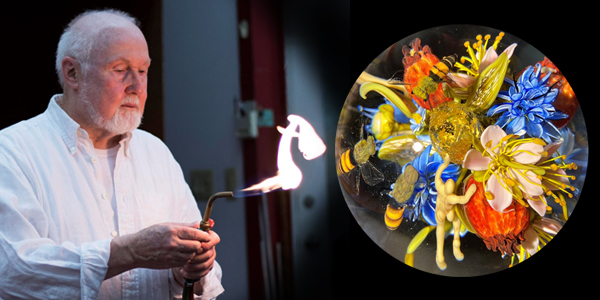

4 – Art of the Flame – Paul Stankard

Take a close look at these incredible glass paperweights and orbs by Paul Stankard, who is considered the American master of flameworking. In 1972, Paul gave up his career in scientific glassblowing, making test tubes and beakers, in order to create floral paperweights. You can watch Paul at work in our video. He melts thin rods of colored glass with a gas-fueled torch and creates perfect petals, pistils, stamens and stems with a blue flame. He arranges these into clusters of flowers with carbon tools and tweezers and embeds them in crystal.

As you view Paul’s work in the cabinets, look in the mirrors to see the underworlds of each piece. During his career, Paul has experimented with different forms, including columns, cubes and orbs. He suspends his flame-worked flowers inside to give viewers different perspectives. Over the years, he has also expanded his mystical views on the life force above and below the earth. His root systems often include little people or earth spirits, which evolved from medieval manuscripts depicting mandrake roots resembling humans. Occasionally, honeybees and other insects hover above Paul’s floral bouquets, and it’s hard to believe they are not real.

The poetry of Walt Whitman has been a significant influence on Paul’s work because of their shared reverence for the beauty of nature. Occasionally, he has been inspired to put pen to paper with his own poems. Paul has written several books about his journey as a glass artist, an incredible achievement for a dyslexic who struggled through high school to find his vocation in glass art.

Paul is an inspirational teacher of flameworking, and he founded the innovative glass program at his alma mater, Salem Community College. He has won countless accolades, honorary degrees, and, more recently, lifetime achievement awards from the glass community.

5 – Contemporary Stars

Local artist Rob Stern is one of the stars of our Hot Glass Gallery. He is known for his iconic Windstars and for his monumental leaves and shells. His stylish glass stiletto shoes are available for sale in the Studio Collection on the second floor. Rob learned glassblowing from the masters, including Dale Chihuly and Pino Signoretto from Murano. Now, with more than 30 years of experience in the hot shop, he travels internationally, teaching a new generation of glass artists. Rob competed in the third season of Blown Away, the reality glassblowing series on Netflix. You can watch glassblowing live at Rob’s studio, which is just ten minutes away from the museum.

You can make your own works of art at Chelsea Rousso’s fused glass workshops which are held regularly at WMODA. See some of the results of Chelsea’s expert teaching in her Unity in the Community installation at the entrance to this gallery. Chelsea discovered glass art after a successful career as a fashion designer and makes wearable glass including bikinis and corsets, which are for sale in the Studio Collection on the second floor.

6 – Threads of Glass

Kiln-formed fused glass is also the specialty of Toots Zynsky, who trained with Chihuly. She developed her own technique using thousands of glass threads, which she calls filet de verre. The process is rather like painting as she lays down her colored glass threads onto a flat surface, ready for fusing. During the firing, she opens the kiln wearing a heat-proof outfit and manipulates the vessels into their final form.

7 – Art Nouveau

Our new museum is in the heart of the South Florida Design and Commerce district, and we have interpreted our vast collection of ceramic art to highlight the important design trends of the last two centuries. The Art Nouveau style blossomed worldwide in the late 19th century and peaked at the Paris Exhibition of Decorative Arts in 1900. French for “new art,” the avant-garde style advocated bringing art into everyday life. Designers abandoned traditional historical motifs and embraced the natural world as a reaction to the increased urbanization of society.

Birds, flowers, trees, and insects inspired organic forms with sinuous curves and dancing lines. Dragonflies and peacocks, with their shimmering iridescent colors, were particularly popular and adorned all types of decorative art, from jewelry to furniture. Innovative potters perfected lustrous glazes reflecting jewel tones and created elegant vases and figurines that glimmered under the gas lights of the times.

Sensual renditions of the female form also inspired the decorative arts of the era.

Artistic homes featured scantily clad figures of alluring maidens by European porcelain designers. Goldscheider of Austria developed a simulated bronze glaze effect for large terracotta sculptures and produced more affordable interior décor for art lovers.

Beautiful women were also the muses and customers of René Lalique, the famous French Art Nouveau jeweler who turned his attention to glass perfume bottles in the early 1900s. He developed cost-effective methods of molding relief-figured designs in glass art as he wanted his luxury designs to be affordable for all classes of society. The 1925 Paris Art Deco Exhibition marked the pinnacle of René Lalique’s career as a glassmaker.

The Art Nouveau style flourished in architecture and interior design until the First World War, and connoisseurs of beauty shopped at fashionable stores such as Liberty’s in London and Tiffany’s in New York.

8 – Proud as a Peacock

The proud peacock was the muse of the Aesthetic movement, and its iridescent feathers adorned the “House Beautiful” in the late 19th century. The mahogany cabinets in this room were made by Shapland & Petter, leading British furniture manufacturers of the era, and they are inlaid with exotic peacock designs in fruitwood and mother of pearl.

Victorian art potteries produced many peacock designs to decorate the Aesthetic home. William Moorcroft designed Florian Ware vases with peacock feathers in the early 1900s. These were sold through Liberty’s London emporium of exotic home décor. The style was revived for Liberty’s nearly a century later by Sally Tuffin at Moorcroft’s modern studio.

In Art Nouveau Europe, the Nymphenburg factory’s porcelain peacock strutted right out of paradise with its marvelous train of feathers. The central Winged Beauty was created by the Lladró porcelain factory in Spain in 2012 and epitomizes heavenly beauty.

William Morris, the visionary Arts and Crafts designer, incorporated peacocks into his textile designs. The Forest fabric is still made by Morris & Company today. Peacock feathers inspired the beautiful velvet fabric from Liberty’s, first introduced in the 1870s and still being sold today.

Thank you to the Nessen Group for arranging the donation of the Morris and Company’s peacock fabric. Thank you also to Jeffrey Michaels and Fabricut for Liberty’s Hera fabric.

9 – The Dragon’s Den

The Chinese dragon controls water and weather, and it was a cultural symbol of the emperor’s power. Dragons and hybrid serpentine monsters have appeared on European porcelain since the 18th century. The vogue for Chinoiserie gave way to Japonism after trade with the West began in the 19th century. Japanese arts and crafts were a sensation at the World’s Fairs of the 1860s and 70s, and new stores such as Liberty of London were catering to the desire for all things Japanese.

Christopher Dresser was the first European designer to study in Japan and is regarded as a pioneer of modern industrial design. He became a household name in the 1870s for his home furnishings, including textiles and ceramics. Dresser designed moon flasks and vases for the Minton factory using their brilliant turquoise glaze known as blue celeste after the “Celestial Empire” of China, where it originated.

In Chinese mythology, snakes are referred to as “little dragons.” After thousands of years, they grow wings to become divine dragons. Charles Noke at Doulton’s Burslem factory created vases with gilded dragons for the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893. Later, he incorporated exotic dragons in his Sung wares displayed on the wall opposite. Wedgwood’s dramatic Dragon King is the largest vase ever made for the Fairyland Lustre collection. You can see more of our Fairyland Lustre collection in the adjacent Art Deco Gallery.

The two Great Dragon sculptures were made in 2012 by Lladró of Spain for their prestige porcelain collection. Thank you to Jeffrey Michaels, our neighbor on 29th Avenue, for arranging the display of Clarence House Tatsu fabric by Fabricut and to Fran Nessen for loaning the Asian table.

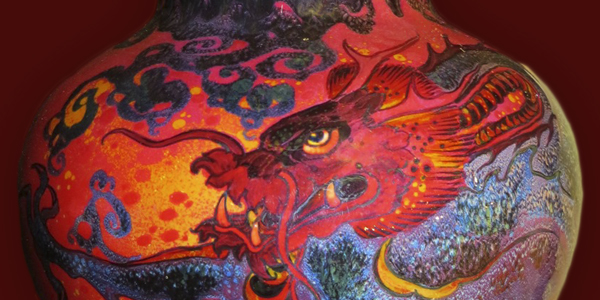

10 – Red – The Fired Arts are Hot

Red is the color of love, as well as danger and sin. Red has also been a symbol of wealth and status. Red-glazed porcelains were created for sacrificial use by Chinese potters of the Ming Dynasty when Imperial rituals required red for worshipping at the altar of the sun. Sang de Boeuf, an ox-blood color glaze, was revered for its rare beauty and became known as flambé after the French word for flames.

European potters experimented to rediscover the lost art of Chinese glazes in the 19th century. By trial and error, they found that copper will produce an intense red color if the kiln is starved of oxygen during a high-temperature firing process. However, it was hard to control the coal-fired kilns and creating a reducing atmosphere with combustible materials led to unpredictable results.

In the early 1900s, Royal Doulton’s Art Director, Charles Noke, experimented with transmutation flambé glazes and added compounds of tin and iron to create flashes of lustrous yellow, blue and purple in the copper-red reduction glazes. Noke called his new ware Sung as a tribute to the ancient dynasty of Chinese potters who pioneered the use of high-temperature glazes.

In his quest to turn common clay into dazzling works of art, Noke likened himself to an ancient alchemist, an image used on the cover of the first promotional catalog for Sung wares introduced in the 1920s. The original watercolor can be seen on the wall alongside an Alchemist vase. Mottled, veined and feathered designs were combined with dramatic underglaze paintings of exotic peacocks and Chinese dragons soaring through fiery red skies.

The adjacent gallery has many more examples of brilliant red glazes by British potteries, including Bernard Moore, Ruskin, Moorcroft and Pilkington.

11 – The Enchanted World of Fairyland Lustre

WMODA has a spectacular collection of Wedgwood’s Fairyland Lustre ware, which has enchanted collectors since the Art Deco Era. War-weary Europeans escaped into a world inhabited by fairies, dragons, imps and goblins, visualized by designer Daisy Makeig-Jones. Daisy joined the Wedgwood factory as a trainee decorator in 1909, and her Fairyland collection was launched in 1915 using the commercial luster glazes newly developed by Wedgwood. These were highly complex preparations of metallic compounds combined with oils and resins, which could be painted on top of the glaze. The Fairyland decorating process was complex; up to six firings were required to achieve the glimmering rainbow effects.

In 1921, Daisy wrote Some Glimpses of Fairyland, in which she presented her versions of popular fairy tales from around the world. Many of her images were derived from Victorian and Edwardian fairy books published during the golden age of book illustration, which were enjoyed by adults and children. Belief in fairies flourished in the early 1900s and led to great interest in Daisy’s designs. James Barrie’s play Peter Pan presented Tinkerbell to a delighted audience. In 1917, two young girls in Cottingley, England, allegedly took photographs of fairies, which caused a sensation after they were published by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes. In their old age, the photographers confessed to using paper cut-outs, but Conan Doyle went to his grave believing in fairies.

Daisy’s fairy folk frolic in a Celtic twilight of fantasy forests with trees and cobwebs intricately outlined in gold. Her fairies don’t have gossamer wings or diaphanous dresses. They are usually mischievous gnomes and pixies, which are grotesque at times. Ghosts and demons also haunted Daisy’s fantasy world. Although charming on the surface, one of her most sinister designs features bubbles filled with fairies, which are eaten when they are caught by Arachne, the spider.

The popularity of Fairyland waned after the Wall Street Crash of 1929, which caused the collapse of the luxury market. Daisy was asked to retire from Wedgwood, but she refused to leave. After an angry meeting in 1931, she stormed out, ordering her assistant to smash all the vases and bowls in her studio. Today, Fairyland Lustre ware is as elusive as the fairies themselves.

12 – Flappers, Vamps & Divas

The Art Deco style is particularly important to South Florida. The City of Hollywood was incorporated in 1925 at the dawn of this exciting new era, which is celebrated in this gallery. The Art Deco style emerged at the Paris World’s Fair in 1925 and featured abstract decoration with geometric shapes inspired by machines and manufactured objects. Art Deco skyscrapers vied for dominance over the New York skyline, while in Miami Beach, Art Moderne architecture introduced aerodynamic curves and nautical influences inspired by the transatlantic ocean liners during the 1930s.

The Roaring Twenties inspired porcelain figurines by Royal Doulton, Goldscheider, Rosenthal, and many other European factories. Their flappers, vamps and divas showcase the vogue for veil dancing and burlesque cabaret performances in the Jazz Age. Diaghilev’s Russian Ballet caused a sensation in Europe with their rhythmic dancing, radical choreography and fantastic costumes by Leon Bakst, adapted by party-going revelers.

Women’s suffrage was achieved in Britain and America by 1920, and young women cast off their corsets, encouraged by the French couturier Paul Poiret. He advocated a natural silhouette using a supple girdle to compress curves. In the mid-1920s, a drastic shortening of skirts exposed women’s legs as never before, shocking the older generation, and hair was bobbed or cut in a boyish crop.

Sunbathing at the seaside and lido became fashionable in the 1920s, and mixed bathing became socially acceptable. The younger generation sported new figure-hugging swimsuits, but decency police roamed beaches with measuring sticks to ensure modest costumes. The 1930s was the “Golden Age of Hollywood,” and sensual pin-up photos of the stars presented a new concept of glamour. Elegant women wore slinky satin gowns, and skirts descended to ankle length. Hollywood’s Hays Code of censorship in the early 1930s heralded a new moral climate and the Glamorous Thirties replaced the Roaring Twenties.

13 – A Colorful Life – Clarice Cliff

Clarice Cliff was the diva of the British pottery industry during the Art Deco era. She started her career in the pottery industry as a gilder at 13 years old and was promoted to company art director in 1930 at the age of 31, a meteoric rise!

Clarice’s Bizarre ware was introduced in 1927 at the Newport Pottery in Stoke-on-Trent. Her exuberant orange, yellow and green designs became hugely popular with British homemakers, enlivening their drab surroundings after the trauma of the First World War. Within a year of the launch of Bizarre Ware, Clarice was supervising 70 young women hand-painting new geometric and angular shapes that she designed.

Clarice Cliff took inspiration from contemporary art as well as nature. Sunrays shine through stylized trees, and Egyptian motifs from Tutankhamun’s tomb mingle with Cubist-style abstracts. Clarice became known as the “Sunshine Girl,” and demand for her designs continued during the 1930s despite the Great Depression. In addition to designing ornamental vases and tea wares, Clarice modeled figurative pieces, including wall masks, which can be seen on the adjacent wall.

Clarice’s “Bizarre Girls” gave painting demonstrations wearing artist smocks and French berets at department stores such as Harrods and Selfridge’s. Photo opportunities with celebrities of the day and other novel marketing ploys led to unprecedented publicity in the national press. The public was fascinated by this new career woman of the 1930s, one of the first female art directors in the pottery industry and one of the first to brand her work. Clarice’s output was impressive until World War II began in 1939.

Clarice’s colorful life story is told in the movie The Colour Room.

Step back in time and explore ceramic art from the Regency and Victorian eras on the second floor. You can take the elevator or the stairs at reception.

Continue the tour upstairs

The elevator is located next to the emergency exit doors. If you prefer, the stairs are located in the reception area.

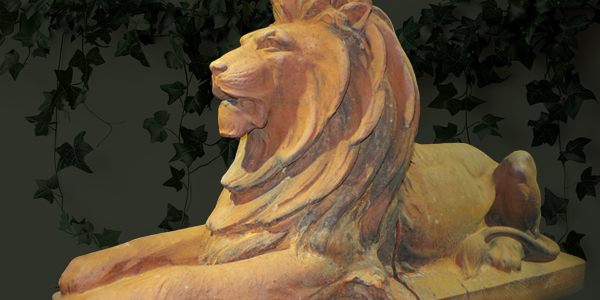

14 – The Lion King

Our Lion King was modeled by John Broad at Doulton’s Lambeth Pottery in 1904. The terracotta statue was created as part of a memorial to Queen Victoria after she died in 1901. Terracotta literally means “cooked earth,” and it was widely used for architectural purposes. The Doulton Studio specialized in making terracotta ornaments for buildings and had huge kilns in Lambeth for firing monumental sculptures. You’ll notice that the massive terracotta lion was made in two pieces so that it would fit into the kilns.

John Broad also modeled architectural details for buildings and one of his most famous commissions was Harrods department store in London which is entirely clad in Doulton terracotta. Doulton’s leading artists also produced terracotta statues that adorned public parks and private gardens and our collection ranges from classical muses from the Victorian era to playful pixies from the 1920s.

The statue of Cupid riding a dolphin was designed by George Tinworth as part of a fountain design for the Philadelphia World’s Fair in 1876. Terracotta was the perfect material for garden ornaments being made from the earth from which all plant life springs. It was used for garden urns and bird baths – even our Sphynx bench is made of Doulton terracotta.

15 – Arts & Crafts Movement

“Have nothing in your home which you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful” was the mantra of the celebrated Victorian design reformer William Morris. After the Great Exhibition in 1851, Morris was at the forefront of the British Arts & Crafts Movement, and he established a company with his artist friends using pre-industrial arts and crafts to decorate Victorian homes.

The Aesthetic Movement also influenced interior design in the late 19th century and rebelled against soulless designs produced by machines. Handmade art pottery was admired for reflecting the vision of its maker and played an essential role in creating an artistic home.

Henry Doulton began experimenting with art wares in 1871 using the salt-glazed stoneware body typically used for drainpipes and industrial wares. The new art pottery was very well received at the international exhibitions of the period and earned the admiration of Queen Victoria. By the 1880s, the Doulton studio employed more than 300 women decorating vases and wall plaques and Sir Henry Doulton made it socially acceptable for women to earn a living in the decorative arts. You can see some of Doulton’s most spectacular exhibition designs by Miss Hannah Barlow and Miss Florence Lewis, the leading lady artists, in this gallery.

At the turn of the century, sophisticated shoppers patronized Liberty’s emporium in London to acquire the latest designs. William Moorcroft launched his successful Florian ware in 1897 and it was so successful that Liberty’s helped Moorcroft build his own factory which still makes beautiful art pottery today more than a century later.

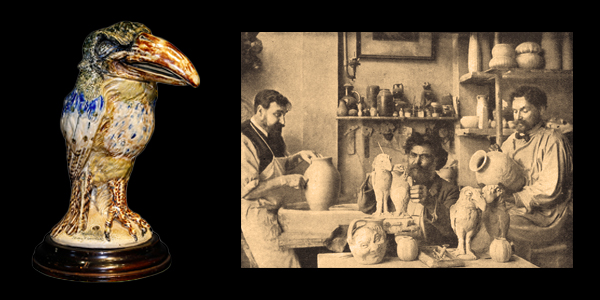

16 – Victorian Humor – The Martin Brothers

Three brothers from the Martin family produced the most bizarre designs of the Victorian Arts & Crafts Movement. They worked together at their studio in Southall, London, from 1877 until the early 1900s. Robert Wallace Martin was a sculptor by training and worked in terracotta and stoneware, cheaper alternatives to stone. Walter Fraser Martin was responsible for throwing the vases and managing the salt-glazed stoneware firings. Edwin Bruce Martin decorated vases with incised designs of dragons, flowers and fabulous fish. His underwater scenes were supposedly inspired by fanciful accounts of microscopic life in the polluted River Thames. Another brother, Charles Martin, sold their work at their London shop until it was destroyed by fire in 1903.

Robert Wallace Martin is best known for his quaint bird jars with whimsical expressions, also known as Wally Birds. They represent professional types familiar to Victorians, including generals, admirals, judges and barristers. They were decorated in various glazes, and in some cases, the head of the bird swivels, which adds to the humor of the subject. Wallace’s wilder fantasies included imps, hobgoblins, reptiles and strange hybrid beasts, which evoke the boojums and snarks from Edward Lear’s Book of Nonsense and Lewis Carroll’s wondrous creatures from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. It was once said that Lear, Carroll and Martin dreamed similar dreams, but Wallace dreamt them in clay and baptized them with flame.

Robert Wallace Martin’s leering and grimacing face jugs were also popular with intrepid customers. His inspiration was Janus, the two-headed god of Roman antiquity, and masks of Bacchus, Pan and satyrs. The Martin Brothers studio survived the onslaught of the Great War in 1914, by which time three of the brothers had died. Robert Wallace, the oldest of the brothers, lived until 1923.

17 – Sermons in Terracotta

This monumental terracotta sculpture was modeled by George Tinworth at Doulton’s Lambeth Pottery in 1885. It depicts Samson, a leader of the ancient Israelites, whose story is told in the Bible. The panel shows the Philistines taking Samson’s hair while Delilah stands mocking him. Tinworth’s quirky sense of humor can be seen in the laughing monkey hiding in the vase and the subtext. Look closely under the title and you’ll see a hidden message, “What you must expect if you get into bad company.”

George Tinworth grew up in an impoverished family with strong Christian beliefs. The Bible was his daily text and he had little formal education. He trained as a sculptor at the Lambeth School of Art and the Royal Academy Schools and was the first artist to be given a job at the Doulton factory. Biblical panels, known as his “Sermons in Terracotta, were Tinworth’s main focus throughout this career.

However, as relaxation from his prestigious commissions, he amused himself with little models of mice engaged in popular Victorian pastimes. Apparently, he couldn’t bear to trap the cheeky rodents that invaded his studio, and he gave them human personalities. Tinworth’s mice take tea, go on vacation and even get drunk. His frogs tend to indulge in sporting activities. Henry Doulton was particularly enthusiastic about these humorous little animal figures and commissioned them as conversation pieces for menu cards and place cards for his friends and family.

18 – Art Pottery – Minton

This Minton tile picture is one of the most admired artworks in the museum. The little girl is being comforted by her dog as she spends some time out on the naughty steps. It was inspired by Briton Rivière’s oil painting entitled Sympathy, which was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1878. Rivière achieved immense popularity with the Victorian public for his animal paintings.

Minton’s Art Pottery Studio was established in Kensington Gore, London, in 1871. Around twenty young ladies were employed to decorate plaques, tiles, vases and flasks with designs by famous artists. The London studio was destroyed by fire in 1875, but hand-painting on pottery continued at Minton’s Stoke-on-Trent factory.

Painting on pottery also became a fashionable pursuit with amateur artists in the 1870s. Leading London china shops held pottery painting classes with blank pottery and other materials provided by the Staffordshire Potteries. Howell and James opened a gallery for annual exhibitions, and more than 1,000 works were exhibited at their 1878 show, which attracted more than 10,000 visitors in two months. The vogue for pottery painting was so intense that the female artists were parodied in the press. George du Maurier’s Chinamania cartoons for Punch magazine satirized their efforts.

Framed pottery tiles and plaques were very popular as wall hangings in Victorian parlors as they were practical and ornamental. Unlike oil paintings and watercolors, they never faded and could easily be wiped clean from the soot and grime from coal fires and oil lamps.

The drapes were designed by William Morris who established a company with his artist friends using pre-industrial arts and crafts to decorate Victorian homes. Morris & Company fabrics have continued to be popular to the present day, and two of his favorite patterns, Strawberry Thief and Bullerswood, have been donated to WMODA by the Sanderson Design Group.

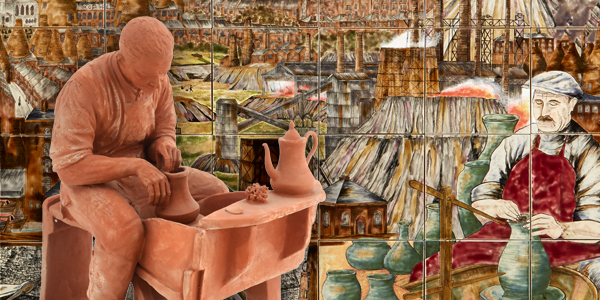

19 – The Staffordshire Potteries

The tile mural on display depicts the Staffordshire Potteries in prosperous times and was designed by Philip Gibson of the Cobridge Pottery to mark the new millennium in 2000. Only two panels were made, and the other remains in Stoke-on-Trent.

As you view the mural and video, you’ll be transported to smoky Stoke. In the 19th century, the skyline was dominated by thousands of bottle kilns emitting thick smoke that engulfed the six Potteries towns. Stoke, Burslem, Hanley, Longton, Tunstall and Fenton merged to become the city of Stoke-on-Trent in 1910. By the 1950s, coal firing had been replaced with gas and electricity and the remaining bottle kilns are preserved today at museums and heritage centers.

The Staffordshire Potteries have been the heart of the British ceramic industry since the 17th century. The region’s rich resources, including clay, salt, lead, and coal, enabled large-scale pottery production. In the 18th century, James Brindley’s canal system revolutionized transportation, allowing raw materials and finished products to move efficiently from the Potteries towns to English seaports via the Trent and Mersey Rivers. This infrastructure, combined with the import of superior white-firing clays from Cornwall and the innovative spirit of the potters, led to a boom in the production of tableware and ornamental ware, many of which were exported to Colonial America.

Peggy Davies modeled the terracotta figures in the case below in the 1980s to celebrate the traditional industries of the Potteries. The potter is throwing a vase of clay on his wheel. To “throw” a pot is derived from old English, meaning to twist or to turn. The Moorcroft vases were made to celebrate the urban landscape of the Potteries and mark the 100th anniversary of their Cobridge factory in 2013. The factory is still operational today, and their surviving bottle kiln features prominently in the atmospheric designs. You can see some of their prestige vases and watch a video of Moorcroft pottery production in the adjacent galleries.

20 – Crowning Success – Doulton’s Diana Vase

The Diana Vase, Charles Noke’s masterpiece, was initially modeled at Doulton’s Burslem Art Studio in Staffordshire for the prestigious Chicago Exhibition in 1893. It was so well received that another Diana Vase, shown here, was made for the Paris Exhibition in 1900. A figure of Diana, the Roman goddess of the chase, crowns this superb Renaissance-style design. One side, painted by Frederick Hancock, depicts Orpheus enchanting the animals with music from his lyre. The other side, painted by George White, portrays Orpheus and Eurydice, the oak nymph he endeavored to bring back from the dead with his music. The vase is further adorned with 22-karat gold by William Skinner.

The historical significance of the Diana vase is profound. Doulton’s finest wares were showcased at the World’s Fairs at the turn of the last century. The Chicago Exhibition was hailed as “Henry Doulton’s greatest triumph,” earning him seven of the highest awards at the exhibition, the most significant number granted to any pottery company. In a testament to their excellence, the Doulton company was granted King Edward VII’s Royal Warrant of Appointment in July of 1901, along with permission from the King to use the title ‘Royal’ in describing their Potteries and Manufactures.

Royal Doulton’s exhibition triumphs continued at the St. Louis Exhibition in 1904. Their artistic prowess was displayed in monumental vases, which provided a canvas for the superb talents of Royal Doulton’s prestige painters, including George White, Charles Beresford Hopkins, and David Dewsberry. These remarkable works of art can be admired in our museum galleries.

21 – The Secret Garden – Victorian Majolica

Victorian conservatories were a symbol of luxury and the pride of wealthy landowners who competed to create the most impressive botanical glasshouses adjacent to their country houses. These imposing glass structures housed tender exotic plants. In winter, they provided a serene space for ladies of leisure to connect with nature and dabble in gardening. In summer, they transformed into vibrant jungle ballrooms, hosting afternoon tea parties and even serving as venues for romantic encounters and marriage proposals.

The high tax on glass was abolished in Britain in 1845, paving the way for a new era of conservatories. The advent of sheet glass manufacturing and cast-iron construction brought these once-exclusive structures within reach of the aspiring middle classes. These technological advances were showcased at the Crystal Palace in London, the venue for the 1851 Great Exhibition. Minton’s new Majolica ware made its debut at this global event. Their vibrantly colored pottery was inspired by the 16th-century French potter Bernard Palissy, and Victorian tributes to his realistic modeling techniques can be seen on the wall.

Minton employed the finest sculptors to create their monumental Majolica wares and brought the renowned sculptor Ernest Carrier Belleuse from France to create masterpieces such as the Mermaid jardinière in the center of the wall. This stunning design was showcased at several World’s Fairs in the late 19th century to demonstrate Minton’s artistic talents. This jardiniere was formerly owned by the Warner Brothers and was featured in their 1982 movie Annie. It was the centerpiece on the dining room table in the home of billionaire Oliver “Daddy” Warbucks as a symbol of his affluence.

Several British potteries specialized in producing garden seats, tables and jardinières for the Victorian conservatory, including George Jones and Royal Doulton. More recently, the Moorcroft Pottery in Stoke-on-Trent has created tiled tabletops for garden décor as in the center of our conservatory.

22 – Art Pottery Past & Present

Art Pottery continues to thrive in Britain today, as can be seen in these three exhibits. The Moorcroft Pottery in Staffordshire uses traditional decorating processes to make their magnificent prestige vases. Raised outlines are applied to the surface of the pottery by squeezing liquid clay from a small rubber bag, similar to icing a cake. You can watch the Moorcroft decorators at work on the video.

William Moorcroft mastered the tube-lining technique for his Florian art wares, which made their international debut at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904. Their success inspired the young designer to open his own factory in Cobridge, which is still operational today and has been producing art pottery continuously for over a hundred years.

The large vase in the center was designed in Moorcroft’s modern studio to commemorate the momentous day in 1913 when William Moorcroft walked with 34 dedicated staff members to his new state-of-the-art factory. The vase incorporates iconic bottle kilns and symbolic flowers bursting into bloom at William Moorcroft’s feet as he approaches his brand-new building.

Sally Tuffin was formerly the design director of Moorcroft’s modern studio before establishing her own studio pottery in Somerset. Since 1993, she has been guiding the talented Dennis Chinaworks team to produce her distinctive designs using traditional potting techniques inspired by the Arts & Crafts Movement.

The monumental vases in the central display showcase the superb talents of Royal Doulton’s award-winning artists at the World’s Fairs in Chicago and St. Louis. Sir Henry Doulton encouraged his artists to create their finest work for these international events with the rousing words, “Be first or not at all, for to be second is to be nowhere.” They certainly marked his words as can be seen in the pastoral paintings by Charles Beresford Hopkins, George White’s ethereal maidens and David Dewsberry’s orchids. The Royal Doulton Story documentary starring Patrick Macnee of Avengers fame is showing on the screen.

23 – Regency and the World of Wedgwood

The earliest works of art in the WMODA collection were made by Wedgwood and are featured in our Regency Gallery. When George, Prince of Wales, became Regent in 1811 due to the king’s mental instability, the prince’s patronage of the arts and his extravagant tastes gave rise to a new artistic era. This was a time of elegant refinement with fashions and interior décor immortalized in Jane Austen’s novels. At the forefront of the consumer revolution was the Wedgwood Pottery, whose London showroom became a destination for the social elite. Shopping was transformed into a cultural activity.

Josiah Wedgwood, the pioneering potter and creative entrepreneur of the 18th century, left an indelible mark on the industry. His systematic experiments at his factory in Staffordshire produced new ceramic bodies, including Creamware, Black Basalt, and Jasper ware, which he decorated in the fashionable Neoclassical style. Statues and busts of ancient Greek gods and heroes were reproduced in the Black Basalt body for decorating neo-classical-style interiors, especially libraries. Take a look at the Black Basalt display in our Wedgwood Library.

Jasper ware, Josiah Wedgwood’s most renowned invention, is a dense white stoneware body stained with metal oxides to create a diverse palette of colors. By 1776, after years of meticulous experimentation, Wedgwood had perfected the iconic blue shade that now bears his name. As you will see here, Jasper ware is not just blue; it was also made in shades of ivory, yellow, green, lilac, crimson, and black and adorned with white relief-figured ornaments applied by hand called sprigging. A variety of colors continue to be made by Wedgwood today.

In 1848, Wedgwood perfected their Carrara ware, named after the Italian marble. The matte white statuary porcelain was first developed by the Minton and Copeland factories and was also known as Parian ware after the marble from the Greek island of Paros. Parian ware figures and busts were commissioned from leading sculptors by the Victorian Art Unions, who acted as patrons of art on behalf of their members. This was an affordable way for Victorians to acquire art.

Take a look at the unusual Black Basalt and Jasper ware objects in the Wearable Wedgwood case, and guess what they are. Surprisingly, they are shoe heels made for the Rayne company in the 1950s and 70s.

24 – Cheers – The Art of Hospitality

Good cheer has been associated with happy faces, holidays, hospitality and plentiful food and drink since medieval times. In the Roaring Twenties, “Cheers” also became a drinking toast in conjunction with the clinking of glasses. Tea was first described as “the cup that cheers but not inebriates” in an 18th-century medical article. The writer argued that tea comes from nature and is healthy, unlike fermented liquors.

Tea drinking was first imported to England from China during the 17th century and aristocratic ladies took after-dinner tea in their homes. The Duchess of Bedford is credited with introducing English afternoon tea in the 1840s after experiencing a sinking feeling between meals. Spiced with scandal and gossip, afternoon tea became a cornerstone of English social life. The beverage became the nation’s favorite brew when more affordable tea was cultivated in India.

Americans developed a preference for iced tea, which made its debut at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904. A few years later, the tea bag was discovered accidentally by a New York tea merchant. He sent out samples of his blends in silk muslin bags and found they were being used to brew the tea without the mess of tea leaves.

Whether you drink tea, coffee, wine, beer or something stronger, we wish you “Cheers!”

Before you leave the Cheers gallery, look at the toby jugs cabinet and you’ll see a Royal Doulton character jug of Merlin, the magician. This was the first piece that Arthur Wiener bought on a trip to London in 1965. Merlin certainly cast a spell on Arthur as he has created a world-class collection for WMODA.

25 – Ardmore Ceramic Art and Design

This magnificent ewer celebrates the first 30 years of the Ardmore Ceramic Art studio in South Africa with icons of the artists’ successes and poignant references to their struggles. The piece was sculpted in 2015 by Sfiso Mvelase and hand-painted by Elvis Mkhize. The snake handle represents Ardmore’s winding and arduous journey, which began in 1985 when Fée Halsted began making ceramic art with a young Zulu woman, Bonnie Ntshalintshali. Their success attracted other women to Ardmore, providing them a means to make a living. The sale of their artworks has helped to uplift this remote community.

The Ardmore Studio was devastated by HIV/AIDS, and more than 30 artists died of AIDS-related illnesses in the 1990s, including Bonnie. One of the most moving images on the ewer is Punch Shabalala being carried home from the hospital close to death. Fortunately, she made a remarkable recovery and is now the studio’s most respected senior painter.

At Ardmore, over 50 artists now collaborate under Fee’s guidance, each contributing unique skills and perspectives to create one-of-a-kind pieces. These artworks are individually modeled and hand-painted, bursting with life as safari animals emerge from lush foliage to form quirky vases, tureens, and teapots. The collection also features exciting forms of sculptural art inspired by Zulu folklore and tribal traditions. The artists work in the spirit of Ubuntu, which means “we are because of others.”

The Ardmore Design collection was launched in 2010, heralding an exciting new direction for the ceramic art studio. Ardmore’s partnership with Hermès, the luxury French brand, began in 2013 with a collection of silk scarves. Since then, Ardmore’s in-house graphic designers have translated the distinctive imagery and playfulness from the ceramics into luxurious fabrics and furniture, including sofas, poufs and pillows. The tabletop collection features tablecloths, runners and napkins for formal dining, and melamine placemats and coasters for casual entertaining.

The Ardmore Design collection is available for sale at WMODA, and all purchases benefit the museum and the Ardmore community.

Return Downstairs

The elevator is to the back of the building, adjacent to the Studio Collection. If you prefer, the stairs are located in the front of the building between the Secret Garden and the Regency Gallery. Once downstairs, the Contemporary Gallery is along the corridor that runs near the front of the building. Also, look into the Special Exhibitions Gallery. The Museum Shop is also in this corridor.

26 – Contemporary Studio Potters

Arthur Wiener, our founder and benefactor, started collecting British ceramics in the 1960s and his collection includes major companies, such as Royal Doulton and Wedgwood, as well as independent studio potters. Some of his favorite contemporary artists have been inspired by potters of the past.

David Burnham-Smith was an expert restorer of Victorian art pottery and revived their decorating techniques in his intricately painted work. Andrew Hull studied the work of the Martin Brothers and continues their tradition today with his quirky bird jars. After a career as a best-selling children’s illustrator, Michele Coxon trained as a ceramic sculptor. She creates whimsical tableaux that are reminiscent of Staffordshire flatback figures.

The natural world has also inspired many contemporary ceramic artists. Roger Cockram was formerly a biologist and draws inspiration from marine life for his vigorous wood-fired stoneware. Maureen Minchin works in the Scottish Highlands, painting the flora and fauna of the remote wilderness on pottery. Nichola Theakston’s sensitive studies of primates illustrate her deep understanding of animal behaviors.

Arthur Wiener also collects work by American artists such as Rose Cabat. Before passing in 2015, Rose was the oldest ceramic artist in America and was still working at her potter’s wheel on her 100th birthday. Her “Feelies” made her a star of the Mid-Century Modern Movement.

Tour End

Thank you for visiting WMODA. We hope we have fired your imagination with the Fired Arts.

Before you leave, we invite you to explore our Museum Shop on the first floor and the Studio Collection on the second floor. There you can purchase one-of-a-kind artworks by artists working in our community and overseas. You can also commission custom designs through WMODA, knowing that your acquisitions benefit the artists and the museum. Speak with a sales associate for details.

Stay connected with us by subscribing to our monthly e-newsletter Through the Looking Glass, which features stories about our collections and details of upcoming events at WMODA. If you’d like to delve deeper into the rich history of ceramics and glass art, our libraries are available for research by appointment.

If you enjoyed your visit, we’d be grateful if you could review us on Google or TripAdvisor and share your favorite photos of WMODA on Facebook and Instagram.

WMODA is a 501c3 not-for-profit museum, and all donations and purchases benefit the museum. Donations to continue the museum’s educational programs are greatly appreciated.