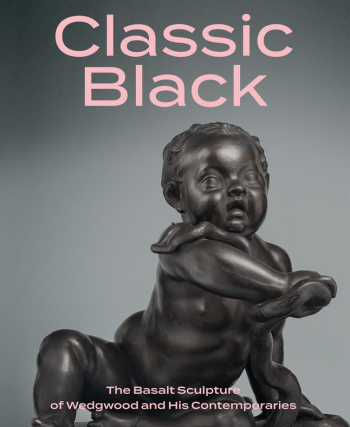

“Black is sterling and will last forever” said Josiah Wedgwood of his new black basalt body. The first major exhibition devoted to the subject has opened recently at the Mint Museum in Charlotte and has inspired us to look more closely at the black basalt collection at WMODA.

Josiah Wedgwood began experimenting with his black stoneware body in 1766 and the first pieces were on the market two years later. His finely textured black stoneware body was achieved by adding manganese and carr, an iron oxide obtained from coal mines. Black basalt could be press-molded or slip cast to make exact reproductions with a lustrous bronze-like surface.

Wedgwood used his new black basalt body to make portrait busts, statues, vases and plaques, derived from Greek and Roman antiquity. Classical gods, orators and philosophers were displayed in gentlemen’s libraries to indicate culture, a classical education, and good taste. Sculptures by Renaissance and Baroque artists reproduced in black basalt were also fashionable in the neoclassical interiors of the late 18th century.

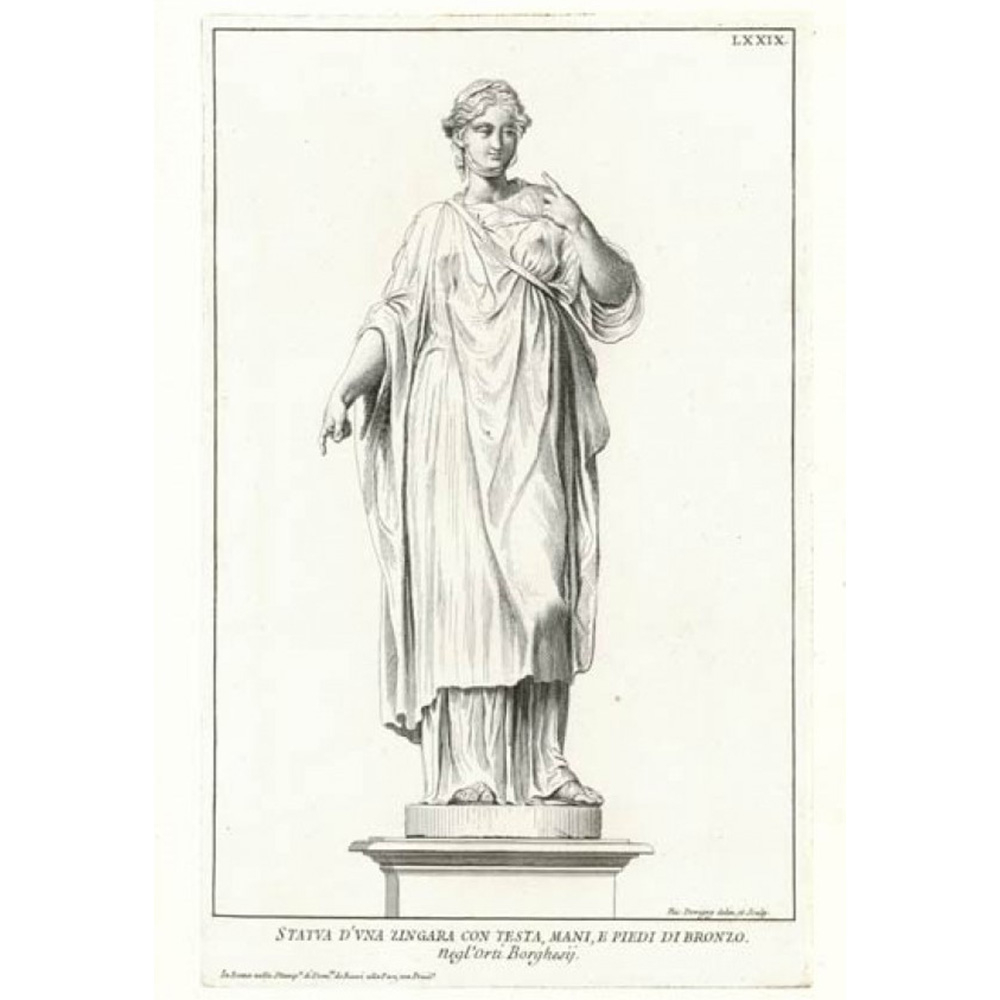

Zingara, the gypsy fortune teller, was based on a Roman marble sculpture with bronze additions, formerly at the Villa Borghese in Rome. The statue was acquired by Napoleon Bonaparte and is now in the Louvre in Paris. Zingara was much admired in the 18th century during the Grand Tours of Europe and Wedgwood commissioned the London sculptors Hoskins and Grant to reproduce the figure in plaster from prints in 1779.

Hoskins and Grant, originally Hoskins and Oliver, provided many plaster models which were finished at Wedgwood’s Etruria factory by William Hackwood. This “ingenious boy”, was how Wedgwood described the precocious, untrained modeler whom he employed in 1769. Ultimately, Hackwood became Wedgwood’s head of ornamental art in a career that spanned over 60 years. Hackwood’s talents brought many celebrities to life as black basalt library busts for the appreciation of the public before photography was invented. His abolitionist medallions, Am I Not a Man and a Brother, modeled for the anti-slavery movement, were widely distributed in the 18th century.

Many distinguished artists of the time worked for Josiah Wedgwood, including John Flaxman Junior, who modeled the black basalt library bust of Mercury, and George Stubbs, whose painting inspired the oval tablet depicting the Frightened Horse. Works such as these first appeared in black basalt in the late 18th century but continued to be popular through the 19th century and even into the early 20th century. The Frightened Horse, first issued in 1780, was reissued as a limited edition of 250 in 1973.

Some of the finest black basalt sculptures at WMODA came from the collection of Victor and Muriel Polikoff, who donated their library to our museum for the study of Wedgwood. The Polikoffs were devoted scholars of Wedgwood and they collected many black basalt sculptures. One of the most imposing depicts William Shakespeare, who is portrayed with a quotation from The Tempest. Literary themes in black basalt were popular for libraries. Longfellow’s Song of Hiawatha inspired an interesting black basalt sculpture of the native American in 1863. Several statues acquired from Polikoff collection depict fauns or satyrs from classical mythology, which are a feature of our Fantastique exhibit. Pan, the god of nature, was initially portrayed with a horse’s tail and later as a half-human creature with the legs of a goat. Wedgwood copied early representations of him from classical statuary for their black basalt sculptures, for example the Piping Faun, which was based on a Roman marble copy of a 4th century BC bronze in the Louvre. Wedgwood was also inspired by the French 18th century Rococo sculptor Clodion and his Infant Satyr and Running Faun were reproduced in black basalt and Majolica.

Classical gods and goddesses of love and beauty were popular subjects for black basalt figures during the 19th century. Highlights at WMODA include Aphrodite, Diana, and Euphrosyne, who attended Aphrodite and Eros as the goddess of good cheer, joy and mirth. She was depicted with Eros/Cupid by the Pre-Raphaelite sculptor Thomas Woolner and reproduced in black basalt by Wedgwood. The sculpture of Cupid Disarmed was modeled by Giovanni Meli, an Italian sculptor who worked in the Potteries in the mid-19th century producing mainly Parian sculptures. The black basalt figures of Cupid and Psyche remained popular for many years and were made also in white and colored glazes.

Cupid and Psyche are often portrayed on Wedgwood tablets and medallions. Their marriage scene was loosely based on the Marlborough gem and the companion Sacrifice to Hymen was modeled by John Flaxman Junior. Scenes of frolicking putti were inspired by the Baroque sculptures of Francois Duquesnoy, known as Il Fiammingo in Rome. His plump putti with carefully observed children’s heads were much admired and used by fellow artists, such as Bernini and Rubens. His Bacchanal scene inspired a black basalt tablet and several of his children were produced as paperweights and known as the “Five Boys of Fiammingo”. One of the largest black basalt tablets in the Wiener collection depicts the Death of a Roman Warrior, which was derived from a sarcophagus in the Albani collection now in the Capitoline Museum in Rome. The relief modeled panel was first introduced in 1773 but production was limited due to firing difficulties. WMODA recently received a generous donation of an 18th century circular plaque depicting Marsyas and the Young Olympus from the Starr and Wolfe family.

Josiah Wedgwood aspired to be the “Vase Maker General to the Universe” and he produced many black basalt vases for niches in neo-classical interiors of the late 18th century. Usually the Wedgwood vases were derived from engravings of Greek or Roman vases or actual pieces which Josiah borrowed from eminent collectors of his day, such as Sir William Hamilton. His “Estrucan” style vases were painted with encaustic designs imitating Greek originals. In the 19th century, the black basalt vases were sometimes gilded.

Candlesticks in black basalt were practical as well as decorative. They were often inspired by mythological characters, such as the Tritons, who were fish-tailed gods of the sea, and Ceres, the goddess of agriculture and motherly love. Candlelight glimmered seductively on the lustrous surface of black basalt ware and apparently black was very popular for teapots as it contrasted beautifully with the lily white hands of the ladies as they poured tea after dinner. Ultimately, more than 150 potteries produced their own versions of black basalt for ornamental and practical purposes. Black basalt teapot designs by several different makers can be seen in our Art of Tea exhibit, courtesy of Angela Scott.

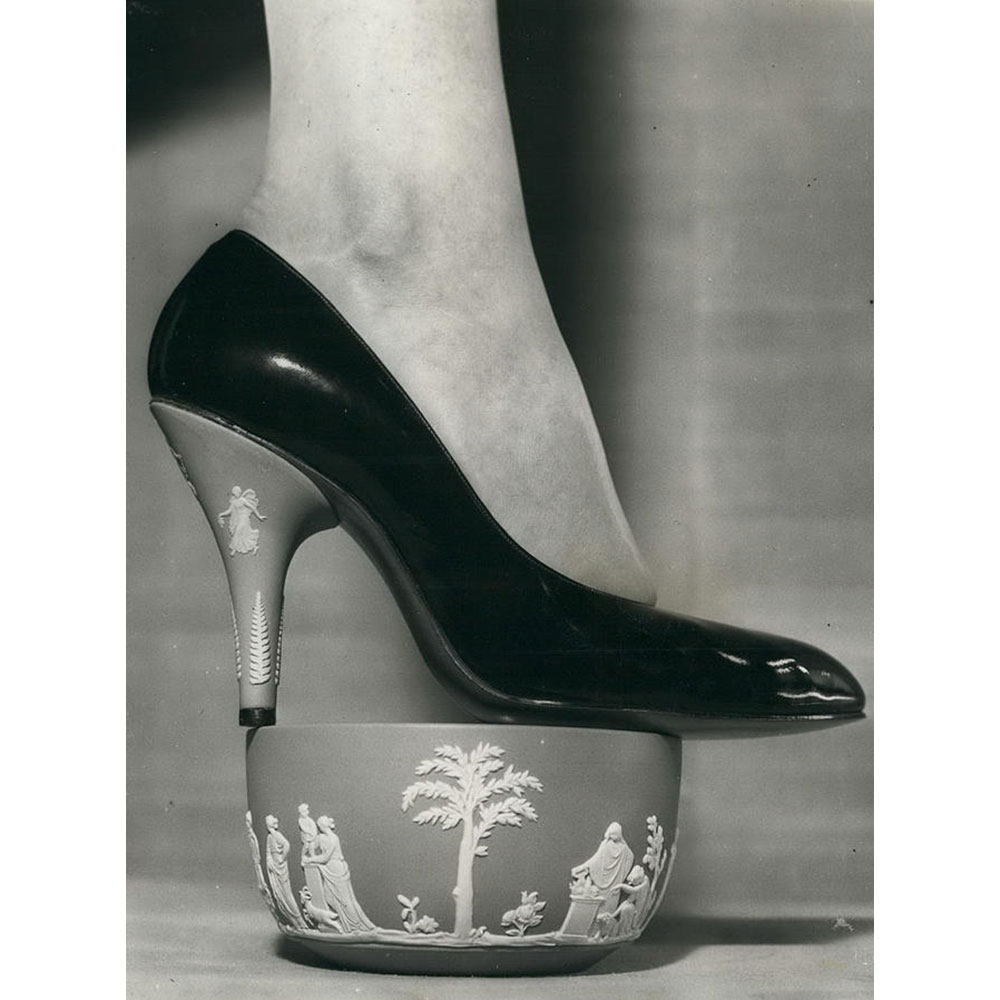

Black basalt continued to be popular into the 20th century and Ernest Light was commissioned to model a collection of little animals and birds in 1911, often with glass eyes. One of the most unlikely uses of black basalt was for Wedgwood shoe heels first made by Rayne in 1958. Popular subjects of the past were reissued for special events, such as the Apotheosis of Homer which was revived for the Lord Wedgwood collection. In 1969, Wedgwood issued a limited edition of the original anti-slavery medallion in black basalt and the following year produced a portrait medallion for Beethoven’s Bicentennial. Wedgwood’s prediction that his black basalt would last forever continues to ring true.

Read more about black basalt sculpture in the excellent new book by Brian Gallagher at the Mint Museum.

“Classic Black: The Basalt Sculpture of Wedgwood and His Contemporaries”

Black Basalt Britannia Bust

Zingara

Wedgwood Zingara

Wedgwood Collectors Society Medallion

Wedgwood Mercury after John Flaxman

Wedgwood The Fightened Horse

Wedgwood Shakespeare

Wedgwood Hiawatha

Wedgwood Piping Faun

Wedgwood Faun & Goat

Wedgwood Faun and Bacchus

Silenus

Wedgwood Young Pan

Wedgwood Cupid Disarmed

Wedgwood Cupid

Wedgwood Psyche

Wedgwood Eros & Euphrosyne

Wedgwood Sacrifice to Hymen

Wedgwood Death of a Roman Warrior

Wedgwood Hercules

Wedgwood Bacchanal

Bacchanal of Putti

Wedgwood Reclining Child

Wedgwood Marsyas and the Young Olympus

Wedgwood Sacred to Bacchus Ewer

Wedgwood Cupid Vase

Wedgwood Campana Vase

Wedgwood Encaustic Vase

Wedgwood Gilded Basalt Vase

Wedgwood Ceres Candlestick

Wedgwood Triton Candlestick

Wedgwood Triton Candlestick

Wedgwood Teapot

Leeds Death of Nelson

Schiller & Gerbing Teapot

Wedgwood Cat by E. Light

Wedgwood Egret by E. Light

Wedgwood Cockatoo by E. Light

Wedgwood Lion by E. Light

Wedgwood High Heel by Rayne

Wedgwood High Heel by Rayne

Wedgwood showroom detail